On the Stage and On the Page: A Reflection of Celebrity Culture in the Yellow Book

Caitlyn Ng Man Chuen

Ryerson University

2344

Introduction

|

The fin de siècle was a transition period in between the realist trends of the nineteenth century and the modernist styles of the twenties in which art flourished. Fin de siècle England produced some of the most iconic literary works known, such as The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and War of the Worlds, often written in the styles of decadence and aestheticism. Less celebrated, but no less important, are the periodical publications of the era that published and spread works by creators known and obscure. Although its publication period was brief, the periodical the Yellow Book has received attention for featuring “some of the best and most representative literary art” (Weitraub 137) of the fin de siècle. Included in the first volume of the Yellow Book, one that was panned by critics but is now lauded, was an image called “The Old Oxford Music Hall”, a music hall painting created by Walter Sickert from 1888 to 1889 and reproduced for the publication’s April 1894 volume. Found in the April 1896 ninth volume of the Yellow Book, known as one of the worst in terms of quality (Weitraub 149), is a non-fiction essay called “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert” by Stanley V. Makower. |

|

Both of these works included in the Yellow Book feature female performers in a spotlight. Sickert’s painting displays an unknown woman performing in a music hall and Makower’s essay discusses one of the most famous music hall performers of the fin de siècle, Yvette Guilbert. Although many people understand The Yellow Book as an avant garde text, “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert” and “The Old Oxford Music Hall” reveal that it reflects the mass culture and curiosity with female celebrities that was prevalent in 1890s England.

|

The Oxford Music Hall, 1875

Artist Unknown, London Theatre Museum Collection

|

During the fin de siècle, music hall performers relied heavily on advertising to promote themselves. Both the performers and the advertisers benefited through a symbiotic relationship in that their great success and public attention depended on the other (Hindson 122). To the general public, female professional performers exuded a semi-mythological image (Hindson 129) through their advertisements that the public was able to consume through visits to the music hall. An individual, unmistakeable, and iconic image was necessary for the female performer to reinforce and create through promotional material. If the audience was taken to the female performer's persona and character, they could enjoy international success and celebrity status. |

|

An example of such a celebrity is Yvette Guilbert, a French cabaret singer who enjoyed international success and had a number of famous fans including Sigmund Freud and George Bernard Shaw. She was one of the few female performers who became an international celebrity and icon during and after the 1890s. She enjoyed success across Western Europe, especially in France and England, and in Canada and North America as well.

|

On the Stage and On the Page: A Reflection of Celebrity Culture in the Yellow Book

Caitlyn Ng Man Chuen

Ryerson University

2376

A Love Often Duplicated

An advertisement showing Yvette Guilbert, 1891

Jules Cheret

|

In Stanley V. Makower’s

“On the Art of Yvette Guilbert”, much of the essay is used to discuss the

strong admiration that Makower has of Guilbert and her art form. Makower

writes, “[Guilbert’s individuality] is an individuality so marked, so rare,

that it almost constitutes by its own force a development by itself,

independent of a place in the history of its art, in the same way that the

strength of Chopin’s individuality makes it almost impossible to put him into

relation with other composers of music” (Makower 62). To say that Makower is a dedicated

fan of Guilbert is perhaps an understatement, as he talks about Guilbert’s art

with such intense and passionate language. However fervent Makower’s

appreciation for Guilbert is, his essay is not the only case in which Guilbert

is discussed with such favourable language to express admiration. In fact,

there are many essays and reviews written in the 1890s and afterward which

express a level of love for Guilbert similar to Makower’s. These writers often

speak of her “genius” (Cumberland 517) art, her “infinite charm” (Simpson 172),

and has been called “incomparable” (Jennings 574). To be frank, what Makower is

writing of is not anything that has not been said already and will continue to

be said about the talented Guilbert for the years following his essay’s publication

in the Yellow Book. Thus, although the Yellow Book seemed to draw many criticisms for being distasteful in its early years, “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert” is nothing revolutionary as the text falls in line with the writings of many of Makower’s contemporaries. Interestingly, Makower’s text is not even a review but simply an essay written in anticipation of Guilbert’s concert. This is not a reactionary text to some sort of event or news, but was written simply because Makower desired to write about it. There is nothing wrong with the text or Makower’s affinity for Guilbert, but the fact that the text was included in the Yellow Book, where the editors most likely sought out Makower as a contributor, is quite significant. While the Yellow Book is perhaps known for featuring works that present experimental art and ideas, “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert” reflects the opinions of the masses and subsequently is a text that would appeal to the masses. Thus, the inclusion of “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert” in the Yellow Book demonstrates that the magazine had a reflexive relationship to the popular culture of the era, despite its avant garde reputation. |

On the Stage and On the Page: A Reflection of Celebrity Culture in the Yellow Book

Caitlyn Ng Man Chuen

Ryerson University

2377

The People in the Music Hall

|

Further, the setting

displayed in Walter Sickert’s “The Old Oxford Music Hall” is one that is quite

familiar. In the Yellow Book, Sickert

offers a number of images which feature the Victorian music hall and other

contributors offer numerous images of other celebrity performers that

frequented the music hall and similar institutions like the theatre, such as

Gabrielle Réjane and Ada Lundberg. Like the admiration expressed for Guilbert

in Makower’s essay, the image of the music hall featured in Sickert’s “The Old

Oxford Music Hall” was perhaps not an uncommon image. |

|

When Sickert began to

initially paint music halls, they were in public distaste because of their

vulgarity (West 53), however this view soon changed.Various sources suggest

that although music halls were initially seen as immoral because of their associations

with prostitution and alcohol (Sturgis 148), the middle class often visited the

halls in the 1890s following dramatic measures took by the owners of the halls

to clean up their reputations (Bailey 85). This included the Empire, which

Guilbert was set to perform at, and the Oxford, the subject of Sickert’s image.

Additionally, the Empire is noted to be something of a meeting place or a club

for “members of the upper class and the bohemian set” (Kift 162). So, given the

two differing theatres represented in Sickert’s image and Makower’s text and

the differing audiences that visited either theatre, it can be said that a wide

variety of people in fin de siècle England attended the music hall. “The Old

Oxford Music Hall” does not display a novel, unexplored territory in its image,

but a common image that would not be unfamiliar for much of the upper class and

middle class. As such, both the middle class and the upper class would have

been exposed to the performers that frequented the music halls. Again, this

reveals that the Yellow Book is not

displaying a revolutionary image in its inclusion of Sickert’s image, but a

common image that is perhaps recognizable to many, thus reflecting the

entertainment culture of the 1890s in England.

|

On the Stage and On the Page: A Reflection of Celebrity Culture in the Yellow Book

Caitlyn Ng Man Chuen

Ryerson University

2378

The Celebrity in Society

Jane Avril, another 1890s celebrity, 1893

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

|

During the 1890s, there

were many female performers, like Yvette Guilbert, that frequented the music

hall. However, not all of these female performers grew to have presences beyond

the stage. Actually, the vast majority of female music hall performers would

not grow to attain celebrity status as Guilbert did. A major contributor to

making a female performer into a celebrity was the media of the time

(Pendley-Hindson 110). Things such as articles, images, and interviews of and

about the performer were prevalent in newspapers and magazines (Hindson 126).

All of this press coverage worked to make the performer relevant in the

cultural landscape. Perhaps, the inclusion of Makower’s text is an example of

this essential pop culture propaganda. This is not to suggest that a

publication such as the Yellow Book would

sell its pages for publicity, but rather that in a time when publications and

the cultural landscape was saturated with images of these celebrities and so

perhaps Makower’s text mirrors that cultural landscape. This would reveal the

extent to which the influence and image of the celebrity would reach, as a text

which was assumed to be a sort of counterculture product would feature someone

that is the product of the masses. This would also perhaps relate to Sickert’s

“The Old Oxford Music Hall” as images of celebrities, the people who would

perform in music halls, were even more common than texts. |

|

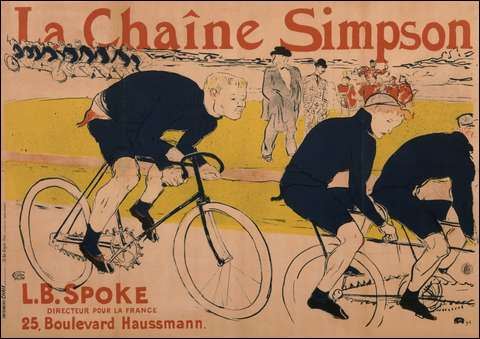

Visual memorabilia, such

as postcards, figures, and posters, existed to cement the celebrity’s image in

the public mindset. Perhaps the most common of all these pieces of visual

memorabilia was the entertainment lithograph, which was essentially a poster

that advertised a celebrity, sometimes when she was making a stage performance,

but not always. Capitalism had given rise to a boom in the advertising industry

and lithographs ubiquitously covered all public surfaces. While perhaps these

lithographs were not images of the music hall or other similar points of

interest that Sickert painted, the music hall remained in the public

consciousness because of these celebrity lithographs. Rather than reflecting

the highbrow, avant garde or bohemian culture of fin de siècle England, as

current readers and studiers of the

Yellow Book may assume, perhaps the publication rather reflects the culture

of the general public as it surely reflects the general public’s consciousness

and preoccupation with the female celebrities of the time.

|

A publicity poster from the 1890s

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

|

On the Stage and On the Page: A Reflection of Celebrity Culture in the Yellow Book

Caitlyn Ng Man Chuen

Ryerson University

2380

To Conclude...

|

Perhaps

an argument that may be offered is that the

Yellow Book has been noted to have declined in both contributors and

readers over the years, especially following the expulsion of art editor Aubrey

Beardsley. Despite the adverse critical reaction to the first few volumes of the Yellow Book and especially to

Beardsley’s art editorship, contemporary scholars acknowledge that Beardsley’s

art editorship contributed greatly to the high quality of the early issues of the Yellow Book. Perhaps if the earlier

volumes reflected a higher quality avant garde taste, then later volumes, such

as the one that Makower’s essay was included in, were lower quality and less

avant garde and more pedestrian. Walter Sickert was published in the Yellow Book fifteen times, spanning

the first five volumes of the Yellow Book,

but never again after that. Evidently, earlier volumes of the Yellow Book were much more controversial to critics, as one

reviewer had remarked that Sickert is merely “disguised as [an] artist” (“A

Yellow Melancholy”). Clearly, this cold reception is indicative of the counter

mainstream area that this particular issue of the Yellow Book was associated with. With such a frequency in

appearances to be cut off following the issue after Beardsley’s termination, it

is possible that the declining quality of the

Yellow Book was reflected in the inclusion of Makower’s essay, however a

more comprehensive argument would be needed for such a claim to be supported. In this exhibit, I have discussed the ways in which “The Old Oxford Music Hall” by Walter Sickert and “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert” by Stanley V. Makower prove that the Victorian preoccupation with the celebrities of the music hall and celebrity culture is reflected inthe Yellow Book. This is not to suggest thatthe Yellow Bookwas and is not a highly influential literary publication and it is not to suggest thatthe Yellow Bookdid not include works that can be viewed as avant garde and experimental. Instead, I only hope to suggest that perhaps there is not a single lens to viewthe Yellow Book. Perhaps as readers in the twenty-first century, over a hundred years after the publication ofthe Yellow Book, we can reconcile that there could be a dual nature ofthe Yellow Book, in which it simultaneously reflects the highbrow culture of the avant garde, bohemian nature of fin de siècle England and the supposed lower culture of the masses. |

|

On the Stage and On the Page: A Reflection of Celebrity Culture in the Yellow Book

Caitlyn Ng Man Chuen

Ryerson University

2381

© Copyright 2015 Caitlyn Ng Man Chuen,

Ryerson University

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study or education.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study or education.

Works Cited

Bailey, Peter. Music hall: the business of pleasure. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1986. Print.

Cumberland, Gerald. “Madame Yvette Guilbert: Impressions and Opinions.” The Musical Times. Aug 1913: 517-518. British Periodicals. Web. 16 October 2015.

Guilbert, Yvette and Harold Simpson. Yvette Guilbert: Struggles and Victories. London: Mills & Boon, Limited, 1910. Print.

Hindson, Catherine. Female performance practice on the fin-de-siecle popular stages of London and Paris: experiment and advertisement. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007. Print.

Jennings, Richard. “Yvette Guilbert.” The Spectator 26 October 1929: 574. Periodicals Archive Online. 13 November 2015. Web.

Kift, Dagmar. The Victorian music hall: culture, class and conflict. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Print.

Makower, Stanley V. "On the Art of Yvette Guilbert." The Yellow Book 9 (April 1896): 60-81.The Yellow Nineties Online.Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. 15 Oct 2015.

Pedley-Hindson, Catherine. “Jane Avril and the entertainment lithography: the female celebrity and fin-de-siecle questions of corporeality and performance.” Theatre Research International 30.2 (2005): 107-123. Web.

Sickert, Walter. "The Old Oxford Music Hall." The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894): 85.The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. 15 Oct 2015.

Sturgis, Matthew. Walter Sickert: A life. London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2005. Print.

Weitraub, Stanley. “The Yellow Book: a reappraisal”. The Journal of General Education, 16.2 (July 1964): 136-152. Web. 23 Oct 2015.

West, Shearer. Fin de siècle: art and society in an age of uncertainty. Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1994. Print.

“’A Yellow Melancholy’: The New Quarterly.” Rev. of The Yellow Book 1. Current Literature. June 1890: 503. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. 16 October 2015.

Bailey, Peter. Music hall: the business of pleasure. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1986. Print.

Cumberland, Gerald. “Madame Yvette Guilbert: Impressions and Opinions.” The Musical Times. Aug 1913: 517-518. British Periodicals. Web. 16 October 2015.

Guilbert, Yvette and Harold Simpson. Yvette Guilbert: Struggles and Victories. London: Mills & Boon, Limited, 1910. Print.

Hindson, Catherine. Female performance practice on the fin-de-siecle popular stages of London and Paris: experiment and advertisement. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007. Print.

Jennings, Richard. “Yvette Guilbert.” The Spectator 26 October 1929: 574. Periodicals Archive Online. 13 November 2015. Web.

Kift, Dagmar. The Victorian music hall: culture, class and conflict. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Print.

Makower, Stanley V. "On the Art of Yvette Guilbert." The Yellow Book 9 (April 1896): 60-81.The Yellow Nineties Online.Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. 15 Oct 2015.

Pedley-Hindson, Catherine. “Jane Avril and the entertainment lithography: the female celebrity and fin-de-siecle questions of corporeality and performance.” Theatre Research International 30.2 (2005): 107-123. Web.

Sickert, Walter. "The Old Oxford Music Hall." The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894): 85.The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. 15 Oct 2015.

Sturgis, Matthew. Walter Sickert: A life. London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2005. Print.

Weitraub, Stanley. “The Yellow Book: a reappraisal”. The Journal of General Education, 16.2 (July 1964): 136-152. Web. 23 Oct 2015.

West, Shearer. Fin de siècle: art and society in an age of uncertainty. Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1994. Print.

“’A Yellow Melancholy’: The New Quarterly.” Rev. of The Yellow Book 1. Current Literature. June 1890: 503. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. 16 October 2015.