Shabnam Yusufzai and Sue Chun

William Holman Hunt

The Victorian era held specific ideological assumptions regarding the roles and characteristics of women. The ideal Victorian woman was considered to be clean and pure, completely detached from sexual connotations. Their main role consisted of domestic duties that took place within the private space of their household. Women were isolated from the outside world – a world that was socially and politically considered a masculine realm. While men actively participated in the public, women were unable to engage in the outside world because it would taint their feminine virtue. This ideological notion of the Victorian woman is widely portrayed within various Victorian works. Alfred Lord Tennyson’s 1842 poem, “The Lady of Shalott”,1 illustrates the stark divide between the gender roles apportioned to the men and women of the Victorian era through an Arthurian context. Tennyson makes use of the interior and exterior worlds to emphasize the notion of the cloistered woman. The tragic themes presented in Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” fascinated the Pre-Raphaelite artists, and as a result, there have been over fifty illustrations of the Shalottian figure created within the second half of the nineteenth century. One of the most famous depictions of Tennyson’s poem is William Holman Hunt’s 1905 oil painting, The Lady of Shalott Although completed in 1905, Hunt had worked on this specific representation of the Lady for over four decades.

Both the poem and painting reinforce the notion of the isolated Victorian woman. Hunt’s illustration however, presents the lady physically entangled within the threads of her tapestry, which is a moment visibly absent from Tennyson’s poem. While Tennyson’s Lady reinforces the Victorian society’s conception of the ideal woman, Hunt’s Lady subverts and violates her prescriptive female role. Tennyson disapproved of Hunt’s illustration, and regarded it to be an inaccurate representation of his poem.

Tennyson: Why is the Lady’s “hair wildly tossed about as if by a tornado?” and why does the web “wind round and round her like the threads of a cocoon?”

Hunt: “I had wished to convey the idea of the threatened fatality by reversing the ordinary peace of the room and of the lady herself.”

Tennyson: “The illustrator should always adhere to the words of the poet!”

Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Lady of Shalott” was first published in 1833 and originally consisted of 20 stanzas. However, Tennyson’s 1842 revision of the poem now has 19 stanzas and was considered by most critics as a much more improved version of the poem.2 Although the poem is titled “The Lady of Shalott”, Tennyson emphasizes more on the setting of the poem and focuses on the Lady’s interior and exterior surroundings rather than the Lady herself. Tennyson shows the Lady’s isolation through her physical situation by contrasting the active exterior world of Camelot to the “four gray walls and four gray towers” that confines her. The cloistered Victorian woman is represented as a passive figure that has accepted her private space where she only engages in the domestic work of weaving.

“She weaves by night and day/a magic web with colours gay”. (II.45)

Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” reflects the ideologies of the 19th century in which Victorian men and women were divided by public and private space. For example, the Lady’s tower is a domestic domain that allows her to weave, which is connected to femininity. On the other hand, the public realm of Camelot is dominated by “bold Sir Lancelot”, which associates the exterior world with masculinity. Although the poem takes place in feudal settings, it is still based upon Victorian England’s society and its principals, values, and patriarchal norms.3 “The Lady of Shalott” is portrayed as pure, proper, and domesticated figure that fits the ideal expectations of Victorian women in the 19th century. Similar to “The Lady of Shalott”, Victorian women had to accept their domestic duties by not engaging in the public realm that belonged to men. Both the Lady’s cloistered position, gender, and occupation shows Tennyson’s construction of the ideal Victorian woman and the role she must serve in society.

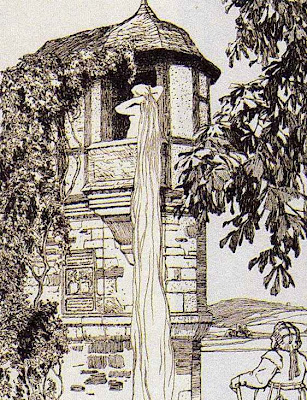

The representation of the cloistered woman in Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” is a universal theme that has been embedded in literature since the conception of fairytales. Tennyson uses fairytale motifs in his poem, which include the portrayal of a fair maiden who is trapped in the tower and is endangered by a curse. This iconic image has now been coined as the “Rapunzel Syndrome” by author Margaret Atwood. One of the key traits of the Rapunzel Syndrome is that the damsel in distress must learn to cope with her cloistered position and internally conform to the societal constraints in which she is situated in. This very description applies to “The Lady of Shalott”, seeing as she does not question or deny her domestic duties of weaving but learns to suppress her emotions in order to fit the ideal feminine role. In Tennyson’s portrayal of the cloistered woman, he does not provide any helpful options for the Lady that will lead to her freedom. For example, the embowered woman is confined within her tower but her escape also leads to her death. “The broadest, most general irony of the poem is that the Lady simply exchanges one kind of imprisonment for another; her presumed freedom is her death.”4 Tennyson explains his views towards women by equating femininity with seclusion through his choice of selecting a cloistered “Lady” – rather than a “Lord” – thus reinforcing conventional Victorian gender roles.

“fed/With clear-pointed flame of chastity…The stately flower of female fortitude,/Of perfect wifehood and lowihead”. (II.1-12)This recurring theme of purity among Victorian women is common in Tennyson’s poems. “The Lady of Shalott” is also portrayed as an innocent figure who is locked in a tower that prevents the Lady from engaging in any sexual acts or thoughts. A few of Tennyson’s female subjects are based on his own personal relationships with women. For example, Tennyson’s poem “Lilian” is based on Sophy Rawnsley, a past lover of Tennyson’s, who was unfaithful within their relationship. As a result of Sophy’s unfaithful ways, Tennyson addresses Lilian’s “innocence” through a male commentator. The masculine voice refers to Lilian as “cruel little Lilian” (II.6) “cunning-simple” and describes her “lightening laughters” (I.16). Tennyson is clearly portraying Lillian (Sophy) in an unflattering light due to his own personal hurt and betrayal he felt from their relationship. The male speaker is arguably Tennyson himself venting his own frustrations about his failed relationship through his poetry. It is evident that Tennyson incorporates personal elements from his life into his work and specifically his assumptions about women’s characteristics.

William Holman Hunt

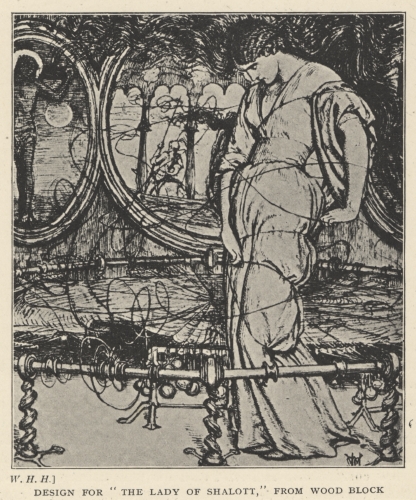

William Holman Hunt’s fascination with Tennyson’s poem, The Lady of Shalott, instigated his series of representations of the Lady.6 Hunt had sketched a variety of Shalottian subjects in 1850, depicting the Lady in several positions at different stages in her life. Amongst these many sketches, one particular illustration – his Study for the ‘Lady of Shalott'”– captures the critical moment of Tennyson’s poem when the Lady looks directly out into the world and realizes her deadly fate:

“Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack’d from side to side; “The curse has come upon me,” cried The Lady of Shalott.”7

Hunt’s depiction of this moment consists of the Lady physically entangled in the threads of her own tapestry, although this is a moment absent in Tennyson’s narrative. It is evident that the concept of this 1850 illustration has lived on through and within his subsequent illustrations including Hunt’s 1857 Moxon wood engraving, Lady of Shalott, and his final 1905 oil on canvas painting, Lady of Shalott. Although the Lady’s physical entanglement remains constant throughout his later illustrations, Hunt had also made important changes throughout his various versions. A significant adjustment can be seen with the lady’s hair, which is tied at the back of her neck in Hunt’s 1850 sketch, but is later transformed into long flowing hair that, according to Tennyson, looks as though it were “wildly tossed about as if by a tornado”8 in his 1857 and 1905 versions of the illustration. It is interesting to note that although Tennyson had confronted Hunt about this element in his 1857 moxon illustration of the Lady, and disapproved of it, Hunt still included it in his final 1905 illustration.

William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood regarded Tennyson as one of their favourite poets.9 Within two decades since the publication of Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott”, the poem had a great aesthetical impact on the Brotherhood.10 Despite this fact, through short conversation between Hunt and Tennyson, Tennyson’s disapproval of Hunt’s depiction of the Lady is evident as he states that “The illustrator should always adhere to the words of the poet!”11 Hunt – along with the Brotherhood – however, was not simply illustrating when painting scenes of a poem. His painting is in itself a new poem created within the context of Tennyson’s verse.12 John Ruskin, a famous art critic who heavily backed the Brotherhood’s work, stated, “Good pictures never can be illustrations; they are always another poem subordinate but wholly different from the poet’s conception and serve chiefly to show the reader how variously the same verses may affect various minds.”13

Jerome J. McGann

Hunt’s portrayal of the Lady as being fallen and sexually charged is perhaps the greatest divergence in Hunt’s painting from Tennyson’s poem. While Tennyson’s Lady remains “passive, docile, and selfless,”14 Hunt’s Lady is presented as a fallen Victorian woman, who “threatens to subvert her prescriptive selflessness.”15 She has become, in a sense, a monster woman who can no longer redeem her lost purity. Hunt conveys this concept through various elements of artistic detail. While Hunt’s original 1850 sketch depicts the Lady with a small – almost frail – frame, she has grown into a “creature” of significant size16 – that would break through the image’s frame if she were to lift her head – in his 1857 Moxon version.

As mentioned earlier, the Lady’s hair has also transformed from being neatly tied at the back of her neck to loose hair that seems to be flying around, out of control.17 The Pre-raphaelite painters were exceedingly fond of women’s hair – especially long flowing hair – which is interpreted as a symbol of female sensuality.18 The Victorian viewer saw unruly hair to be closely associated with uncontrolled sexuality.19 In Hunt’s painting, her hair becomes “a metaphor for monstrous female sexual energies.”20 Her thick and tangled mass of hair is often said to be derived from the mythical creature, Medusa. Her hair appears to be alive and “vibrate with libidinous energy… like a vigorous brood of snakes.”21 But it is not merely the Lady’s hair that resembles the mythical monster, but her very character. Both characters transform from a pure “beautiful” woman to one who is fallen and cursed through the attainment of a sexual conscience. While Medusa’s story is explicit with the sexual element that causes her fall, its connection with the Shalottian figure causes viewers to conceptualize a sexual element of immorality in Tennyson’s Lady. In a sense, Hunt has perverted and violated the ideological innocence of Tennyson’s Lady within the viewer’s mind. Tennyson’s verbal disapproval of Hunt’s portrayal of the Lady’s hair can be seen as a clear expression of disapproval regarding Hunt’s overall representation of the Lady as a fallen woman.

The cloistered woman in Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” lives in a world of shadows. The Lady’s only glimpse of the outside world is through the magic mirror, which is ironically the symbol of her separation.22 The mirror shows only the shadows of others, rather than the Lady’s own reflection. This shows the Lady’s dependency on the outside world and her eagerness to be apart of the social realm but must abide by her cloistered situation. The omission of the Lady’s own image in the mirror represents her non-existence status to the outside world. She sees everything in the mirror that she is not exposed to but wishes to embody and experience: village-churls, market girls, damsels, the abbot, the shepherd, the page, the knights, the funeral party, and lastly the newlywed lovers. Furthermore, it is the very sight of the “two young lovers lately wed” that prompts the Lady to say, “I am half sick of shadows”. As a result, it is the institution of marriage that provokes the Lady’s desire to find martial love and to live in a life outside of shadows. The Lady crosses gender lines by leaving her interior world in order to enter the exterior world of men. Her actions seem to be progressive but because the Lady’s motivation derives from her quest to find marriage. Tennyson is not challenging the status quo but rather reinforcing patriarchal norms. He is also acknowledging the “Women Question” which was a predominant topic in the 19th century, particularly during the time “The Lady of Shalott” was written.23 For example, there was a lot of political debate during this time in England and Tennyson became very much involved with the first Reform Bill of 1832. It can be argued that during this political time involving women’s rights and their role in society, Tennyson wrote “The Lady of Shalott” in response to the poltical events surrounding his society. However, it seems as though Tennyson highlights the anxieties most unmarried Victorian women felt by creating a sense of insecurity within the Lady. Furthermore, the second half of the poem clearly shows Tennyson’s stance on the roles of Victorian women where he punishes his female protagonist by virtue of death.

Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” can also be seen as a didactic poem that has a clear message directed towards Victorian women. It is not until the Lady’s gaze aligns with the outside world of Camelot that ignites the curse. As a result, death is the only suitable punishment for the Lady who dares to look at the public space that is occupied for men. The Lady’s transition from the private/feminine to public/masculine space is seen as a defiant act, and thus serves a didactic message, cautioning Victorian women not to step out of their sphere. Ultimately, “The Lady of Shalott’s” fate is sealed when she reaches land and therefore her movement to the social world is not complete but she is only present in death.24

For ere she reached upon the tide

The first house by the water-side, Singing in her song she died,— The Lady of Shalott. (II.150-153)

When Tennyson had disapproved of Hunt’s illustration he also mentions his disapproval with the Lady being physically entangled in the threads of her tapestry by asking why the web “winds around her like the threads of a cocoon.”25 This concept existed since Hunt’s earliest version of the image – in his 1850 sketch – and therefore is evident that the subversive nature of Hunt’s Lady had existed since his conception of her image. The tapestry symbolizes the redundant domestic role of the Victorian woman. Her unceasing act of this domestic role of weaving keeps her occupied within a confined space thus causing her to remain passive and docile – detached from the outside world. According to Griselda Pollock,

“Patriarchy does not refer to the static, oppressive domination by one sex over another, but to a web of psycho-social relationships which institute a socially significant difference on the axis of sex which is so deeply located in our very sense of lived, sexual, identity that it appears to us as natural and unalterable.”26

The Lady’s tapestry is also referred to as a “web” in Tennyson’s poem and therefore can allude to Pollock’s analysis of the patriarchal web. Hunt’s portrayal of the Lady trying to free herself from the threads that entangle her in his 1850, 1857, and final 1905 versions, symbolizes the Lady’s “unthreading of the web of patriarchal ideology.”27 It is interesting to note Tennyson’s choice of words when he compares the physical entanglement of the Lady to be like the “threads of a cocoon.”28 The Lady’s act of trying to free herself from the threads can be directly compared to the development process of a butterfly. When in the cocoon, the creature is confined within its threads that are anchored to its pupation site – incapable of movement. Upon maturation, the creature emerges from the cocoon, transformed, and free from its static site. The Lady’s forbidden act of looking outside the window is the deciding factor that transforms her into a fallen, subversive woman from her old passive, docile self. As she realizes her inevitable fate, she frees herself from the confinement of her tower, and floats down the river to Camelot as her doomed fate overcomes her.

The Awakening Conscience is an image that mirrors Hunt’s redemption of Miller.32 The woman in the image is also a “fallen” woman who looks directly at the viewer in a horrified manner. There is an unraveled embroidery on the floor with loose threads which is similar to the concept in Lady of Shalott. The difference however, is that the woman in this image seems to be on the verge of picking up the unravelled embroidery – which suggests that she is able to redeem her fallen moral identity. As mentioned earlier, the threads signify a web of patriarchal ideologies.33 Therefore, the woman is essentially redeeming herself by conforming to the patriarchal ideologies she once had lost a hold of. Hunt however, was betrayed by Miller when she defied his instructions.34 Hunts 1857 version of Lady of Shalott can be seen to allude to this betrayal. Miller’s untameable character is reflected in the Lady, who unlike the woman in The Awakening Conscience is permanently doomed. While the woman in his 1853 painting is caught as she is crouching down to retrieve her tapestry, the Lady of his 1857 version, as well as his final 1905 version, is desperately trying to free herself from the threads that are binding her. The Lady’s deadly fate makes it impossible for her to redeem her fallen state.35

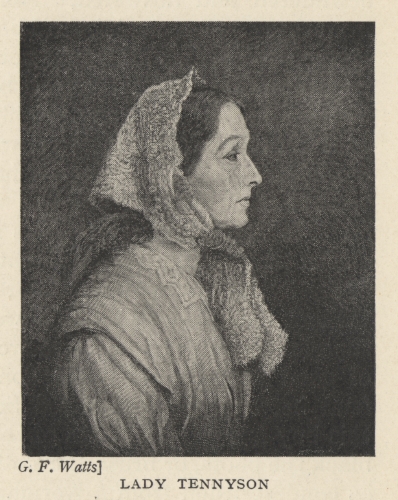

Alfred Lord Tennyson’s own upbringing and history may be a contributing factor towards why he wrote the poems he did and specifically towards his views on the role of women. Tennyson was born on August 6, 1809 at Somersby Lincolnshire and he was the fourth child out of twelve children.36 Compared to his wealthy Aunt Elizabeth Russell and Uncle Charles Tennyson, Tennyson felt poor growing up and became very worrisome about his finances throughout his life. In fact, Tennyson’s anxieties about money became a reality in the late 1830’s when he invested all his inheritance into a mass-producing wood craving business and eventually became bankrupt. Due to his impoverish status, Tennyson postponed his engagement to Emily Sellwood, a woman he has known since childhood.37 This shows Tennyson’s role as a man to be the financial provider in the relationship, seeing as he could not afford to marry Emily. However, in the same year, Tennyson was appointed Poet Laureate (1850) he gained financial wealth and success and thus was able to marry Emily. Furthermore, a letter obtained from The Letters of Alfred Lord Tennyson collection38 reveals an insight into the marriage of Alfred Tennyson and Emily Sarah Tennyson. This letter was written on February 1854 and was addressed to William Bodham Donne who wrote for several quarterlies in the 19th century and served as the chief librarian of the London Library in 1852.39 Tennyson is seeking novels about King Arthur from Donne and he is doing so at the request of his wife, Emily. Similar to her husband, Emily had a keen interest in the late great King and wished for Tennyson to write about him. The manner in which Tennyson speaks about his wife and obliges her request shows his caring nature towards women and most importantly his wife. This letter personalizes Tennyson as a husband abiding by his wife rather than a poet. Although, Tennyson is obliging his wife’s request, he is still fulfilling the conventional gender roles that were required of Victorian men and women. Tennyson is writing for Emily and communicating with the outside world, while Emily can not make this request on her own. This is reflective of the traits of the cloistered woman in Tennyson’s poem, “The Lady of Shalott” who does not interact in the public realm that belongs to men. In a sense, art is imitating life here, seeing as Emily does not have the autonomy to write the letter herself, thus her husband must communicate with the outside world in order to fulfill her request. This letter ultimately reveals that although Tennyson loves and respects his wife, the 19th century ideologies are still deeply embedded within their society that condemns conventional gender roles.

William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt

Another significant aspect of Tennyson’s history involves his consistent fear of succumbing to mental illness. Tennyson’s family has a deep rooted history with madness and therefore he believed the disease to be hereditary. Tennyson’s own paranoia over mental illness could explain the common theme of insanity that is presented in many of his poems and arguably “The Lady of Shalott”. Furthermore, many of Tennyson’s poems not only portray the theme of madness but also connect the disease to femininity. For example, the fear of insanity is Tennyson’s own internal anxieties but yet he selects female protagonists in several of his poems, such as “Mariana” and “The Princess”, to represent the “mad woman.”40 Tennyson is distancing himself personally from his poems by portraying the “mad woman” instead of the “mad man”. Tennyson believed that in order to fight the illness he must study the disease in other people and to write about it through his poetry. For example, it can be argued that the “The Lady of Shalott’s” succumbs to madness due to her isolation in the tower and seclusion from the outside world. The notion of entrapment, femininity, and madness are in direct connection to the common theme of The Mad Woman in the Attic Syndrome which derives from Charlotte Bronte’s, Jane Eyre. For example, some signs of madness arise in the Lady when she escapes the tower and finds a boat, while singing an eerie song until the very last minute she dies.

Heard a charol, mournful, holy”

“chanted loudly, chanted lowly

till her blood frozen slowly”. (II. 145-147)

The “Lady of Shalott’s” punishment for gazing at Sir Lancelot is ultimately death. Victorian women were expected to remain virginal and pure and according to gender assumptions, the Lady violates this rule. As a result, Victorian women who did not abide by these gender roles were marginalized in society. Tennyson stigmatizes Victorian woman who did not follow these conventional Victorian ideals as “mad,” in order to deflect attention away from the problems within his own society and the institution.

Both Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” and Hunt’s Lady of Shalott are expressions of the author and artist’s own personal views on the cloistered Victorian woman. While Tennyson’s Lady reinforced the ideal characteristics of the Victorian woman, Hunt’s Lady is subversive to these conventional female roles. Although Tennyson disapproved of Hunt’s 1905 painting, the painting is not an illustration of Tennyson’s work, but rather a separate tale set in the context of Tennyson’s poem. Both Author and Artist’s works – in a sense – shed light on the emerging progressive role of Victorian women in their society.

Endmatter

1 Alfred Lord Tennyson. “The Lady of Shalott.” 30 Nov. 2004. The Victorian Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

2 Alfred Lord Tennyson. “The Lady of Shalott.” 30 Nov. 2004. The Victorian Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

3 Meg Mariotti. “The Lady of Shalott: Pre-Raphaelite Attitude Toward Women in Society.” 2004. The Victorian Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

4 Shuli Barzilai, “Say That I Had a Lovely Face”: The Grimms’ “Rapunzel.” Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott,” and Atwood’s Lady Oracle”. Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 19.2 (2000): 232.

5 Linda H. Peterson. “Tennyson and the Ladies.” Victorian Poetry 47.1 (2009): 25-43. Project MUSE. Web 24 Mar.2011.

6 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 235. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

7 Alfred Tennyson, “The Lady of Shalott ENG 633: 19th Century Literature and Culture II Course Reader, ed. Lorriane Janzen (Toronto: Ryerson University, 2011)160-162.

8 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 235. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

9 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

10 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

11 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

12 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

13 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

14 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 34. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

15 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 34. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

16 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

17 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 235. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

18 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

19 Shuli Barzilai, “Say That I had a Lovely Face”: The Gimms’ “Rapunzel,” Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott,” and Atwood’s Lady Oracle.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 19.2 (2000): 242.

20 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

21 Shuli Barzilai, “Say That I had a Lovely Face”: The Gimms’ “Rapunzel,” Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott,” and Atwood’s Lady Oracle.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 19.2 (2000): 242.

22 Joseph Chadwick. “A Blessing and a Curse: The Poetics of Privacy in Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott”. Critical Essays on Alfred Lord Tennyson (1993): 83-99. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

23 Carl Plasa. “Cracked from Side to Side”: Sexual Politics in “The Lady of Shalott”. Victorian Poetry Vol.30 (1992):247-263. West Virginia Press. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

24 Meg Mariotti. “The Lady of Shalott: Pre-Raphaelite Attitude Toward Women in Society.” 2004. The Victorian Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

25 Shuli Barzilai, “Say That I had a Lovely Face”: The Gimms’ “Rapunzel,” Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott,” and Atwood’s Lady Oracle.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 19.2 (2000): 242.

26 Carl Plasa. “Cracked from Side to Side: “Sexual Politics in “The Lady of Shalott”. Victorian Poetry Vol. 30 (1992): 247-263. West Virginia University Press. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

27 Carl Plasa. “Cracked from Side to Side: “Sexual Politics in “The Lady of Shalott”. Victorian Poetry Vol. 30 (1992): 247-263. West Virginia University Press. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

28 Shuli Barzilai, “Say That I had a Lovely Face”: The Gimms’ “Rapunzel,” Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott,” and Atwood’s Lady Oracle.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 19.2 (2000): 242.

29 Shuli Barzilai, “Say That I had a Lovely Face”: The Gimms’ “Rapunzel,” Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott,” and Atwood’s Lady Oracle.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 19.2 (2000): 242.

30 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 36. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

31 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 36. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

32 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 36. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

33 Carl Plasa. “Cracked from Side to Side: “Sexual Politics in “The Lady of Shalott”. Victorian Poetry Vol. 30 (1992): 247-263. West Virginia University Press. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

34 Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 36. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.

35 Thomas L. Jeffers. “TENNYSON’S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT.” Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

36 Glenn Everett. “Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Brief Biography.” 30 Nov. 2004. The Victorian Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

37 Marysa Demoor. “His way is thro’ Chaos and the Bottomless and Pathless”: The Gender of Madness in Alfred Tennyson’s Poetry.” Neophilologus 86.2 (2002): 325. Research Library. ProQuest. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

38 Alfred Tennyson to William Bodham Donne, February 1854, Letter 79 in The Letters of Alfred Lord Tennyson: Electronic edition.

39 “William Bodham Donne- Essayist”. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

40 Marysa Demoor. “His Way is thro’ Chaos and the Bottomless and Pathless”: The Gender of Madness in Alfred Tennyson’s Poetry.” Neophilologus 86.2 (2002): 325. Research Library. ProQuest. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.