Aurora Floyd in Cameo

mikolade, Marie Di Filippo, Zachary Hoskins and kristyleigh2012

1645

Mary Elizabeth Braddon's Aurora Floyd in Cameo

cam·eo noun \ˈka-mē-ˌō\ : a

usually brief literary or filmic piece that brings into delicate or

sharp relief the character of a person, place, or event

(Merriam-Webster)

|

What is presented here is a brief series of “cameos” on the sensational novel Aurora Floyd, serialized in Temple Bar between 1862-63. Though Aurora Floyd was

branded "an abomination" by its critics, the populace would send Mary

Elizabeth Braddon’s work soaring to unprecedented heights. Like Aurora,

Braddon was a fashionable, “fast” young woman in the midst of the

quickening pace of Victorian England. Aspects of social spheres reached a

feverish pitch, as a hodgepodge of cultures and classes began buzzing

back and forth, crisscrossing each other on underground trains.

Each cameo will detail a specific “layer” or focus and how it relates both to the novel and to Braddon’s life. Braddon’s life, much like a cameo, consisted of more than “two layers of different colors,” and contained an “inner stratum” differently colored from the outer (“Cameo” OED). The first cameo will look at Braddon’s close association with the sensation movement, and how she became its primary figurehead and, for many critics, a scapegoat. In Aurora Floyd Braddon addresses criticisms of the sensation novel head-on, using devices of allusion and characterization to comment on contemporary literary discourses. Another cameo begins with Aurora Floyd's and Braddon’s mutual love of hunting and horseflesh. Braddon, well-read and intelligent, would have been versed in the controversies of the day surrounding both female and equine fashions, namely the corset for women and the curb-bit and bearing rein for horses. Like other controversies that are present both in her life and her work, such as divorce law and bigamy, the debate over fashion and the parallels between female and equine fashion are undercurrents in her novel Aurora Floyd. |

The third cameo inspects the private life of author

Mary Elizabeth Braddon, through personal interviews and critical public

reviews. The Victorian times in which Braddon lived were heavily

structured in a male/female strata of behavior with a strict moral code

that "pruned" women to be pure and chaste domestic "angels"

of the household. Braddon crossed the boundary lines of predominant ideas,

using the framework of mystery and suspense to show women were more than

idle trinkets. Aurora Floyd experienced passionate emotions, drawing

the reader into her private life of bigamy, black-mail, murder, and

intrigue. Mary Elizabeth Braddon entertained her critics by posting

signature responses to their remarks in the novel itself, publicly

taunting the critics by putting them in their place. She effectively prunes the critics, rather than allowing them to dictate her art.

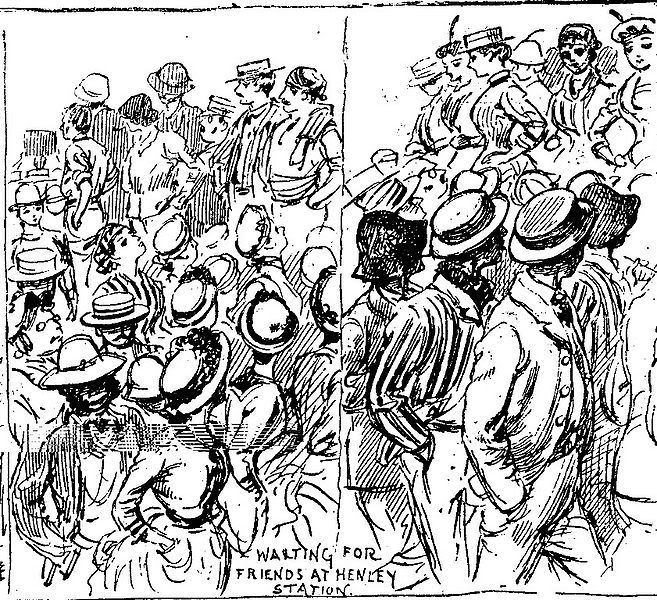

We end with a final relief image of Aurora Floyd fleeing by train without consulting anyone in her domestic sphere, further compromising her already tarnished reputation. Her secrets, kept only because of inescapable situations, become “common property.” This last cameo explores the removal of the stamp tax on newspapers in 1855, giving way to the availability of serialized novels at a cheap rate in railway waiting rooms, just like the one Aurora would have arrived at in Doncaster. This new availability would blur the purity divisions which attempted to carve out high and low literature. Braddon and Aurora conclude that reality is really a much more ambiguous space, where both the high and low, conventional and nontraditional can be embraced in order to reach Truth through narrative.

We end with a final relief image of Aurora Floyd fleeing by train without consulting anyone in her domestic sphere, further compromising her already tarnished reputation. Her secrets, kept only because of inescapable situations, become “common property.” This last cameo explores the removal of the stamp tax on newspapers in 1855, giving way to the availability of serialized novels at a cheap rate in railway waiting rooms, just like the one Aurora would have arrived at in Doncaster. This new availability would blur the purity divisions which attempted to carve out high and low literature. Braddon and Aurora conclude that reality is really a much more ambiguous space, where both the high and low, conventional and nontraditional can be embraced in order to reach Truth through narrative.

Temple Bar

|

Aurora Floyd was published in Temple Bar magazine from 1862-1863. Temple Bar: A London Magazine for Town and Country Readers was

a "shilling monthly" published by Ward and Lock and aimed at a

middle-class readership. Its format, which mixed serialized novels,

essays, reviews and poetry, was largely modeled after William Makepeace

Thackeray's successful Cornhill magazine; Temple Bar's

chief distinction, however, was its policy of including additional text

rather than the popular etchings and woodcuts of other contemporary

periodicals (Blake/Onslow). Perhaps as a result of this policy, Temple Bar had a significantly lower circulation than its primary rival; while Cornhill was maintaining a readership of 80,000 in 1862 (Phegley "Cornhill"), Temple Bar at its height reached only 30,000 readers (Blake/Onslow).

Still, the significance of Temple Bar to Braddon's early career is manifold. Its founder, John Maxwell, had been Braddon's chief mentor since 1860 and her domestic partner (Maxwell was infamously married to another woman during their cohabitation) since 1861. In addition, the magazine's editor during the period of Aurora Floyd's publication was George Augustus Sala, who would later in the decade become a contributor to Braddon's own magazine, Belgravia, and a very public defender of her sensational fiction. In his most famous of such defenses, 1867's "The Cant of Modern Criticism," Sala wrote that "there is a kind of pleasure, mingled with sadness, in assailing [Braddon's] detractors in a magazine she conducts, remembering as I do that it was in a magazine which I conducted--in Temple Bar--that she reached her first station in the highway of Fame" (Sala 55). |

The Writer and Her Work

|

By Kristy Scherba

In "Miss Braddon: The Writer and her Work" by Clive Holland, the family background of Mary Elizabeth Braddon is highlighted, noting they lived as lawful people amidst the quiet rolling countryside of Cornwall, England. The family cultivated literary talent primarily through Mary Elizabeth, who began writing as a child and who exclaimed there was never a time she recalled not writing. Her mother possessed cultured tastes, her father worked as a sports writer, and her brother wrote and published a couple of books; but no one equaled the determined talent of Mary Elizabeth Braddon. In The Writer and her Work, Braddon is praised for revising the element of mystery in sensational fiction,unlike “the sensational rubbish which now pours from the printing press almost every day”(151). Braddon is praised as a great stylist and brilliant writer. In effect, she has come full circle in her lifelong career; first as the criticized, now as the acclaimed. At seventy-four years of age, Mrs. Braddon offers some anecdotes about her writing habits and talks of her first writing position. She was offered a writing job that needed someone to match the humor of Dickens and the plot of Reynolds, an almost impossible role to fill; but eagerly set to work, placing the writing sample on the desk the next morning, and was immediately hired. From there, Lady Audley’s Secret was an instant success; unable to print and bind fast enough to keep up with demand. Aurora Floyd was equally anticipated and well received. Robert Louis Stevenson said, “Aurora Floyd is to be out and away greater and more popular than Scott, Shakespeare, Homer, In the South Seas, and to that you have attained” (152). Clive Holland reports Braddon is esteemed not only in quality, but for quantity of words, filling “generous lines” in lengths exceeding many of her contemporaries. The once severe critics have only to sing praises for Braddon,as a masterful weaver of plot and story, with fifty-six books penned; she is an indomitable force in the industry with unmatched perseverance and style. Braddon talks about her plot ideas when developing a story: “When the plot of my tale has been decided, I carry it about with me, in the shape of portable mental luggage, for a long time. I always write the book with my own hand, with no preference where and no particular time for writing”(153). At seventy-four, she has no love for publicity and prefers the solitude of the country. Her hobbies are traveling, gardening, music, and reading, but her love of horse riding has ended due to age; she has always been fond of children and animals. Her favorite writer is Charles Dickens, and her advice to new authors is: “wait until some incident in real life suggests the subject of a story and when you have let it grow and shape itself in your mind, tell your story and tell it in the best language and in the simplest manner possible” (153). That, she declared, is the best advice she can give anyone. |

Aurora Floyd and the Critical Discourse of Sensation

By Zachary Hoskins

By the time of Aurora Floyd’s writing and serial publication in 1862-1863, debates over the aesthetic and moral legitimacy of the sensation novel were already growing in prevalence throughout Victorian print culture. Toward the end of the decade, Braddon—by then widely considered both figurehead and scapegoat for the movement—would enter the fray herself, commissioning defensive essays like George Augustus Sala’s “The Cant of Modern Criticism” in the pages of her monthly magazine Belgravia. Yet a sly form of self-conscious criticism can also be detected in Braddon’s own novel, which uses the devices of allusion and characterization to comment on these contemporary discourses, and to solidify a place for sensation novels in the Victorian cultural hierarchy.

By the time of Aurora Floyd’s writing and serial publication in 1862-1863, debates over the aesthetic and moral legitimacy of the sensation novel were already growing in prevalence throughout Victorian print culture. Toward the end of the decade, Braddon—by then widely considered both figurehead and scapegoat for the movement—would enter the fray herself, commissioning defensive essays like George Augustus Sala’s “The Cant of Modern Criticism” in the pages of her monthly magazine Belgravia. Yet a sly form of self-conscious criticism can also be detected in Braddon’s own novel, which uses the devices of allusion and characterization to comment on these contemporary discourses, and to solidify a place for sensation novels in the Victorian cultural hierarchy.

|

Many

19th century novels contain some level of self-reflexivity in their

narration; Aurora Floyd, however,

engages this tendency to an unusually great extent. Braddon’s narrator

frequently refers to the novel as a text in the process of being written,

rather than merely a story being recounted. Describing Talbot’s love for

Aurora, for example, she interjects, “I must write his story in the commonest

words. He could not help it!” (Braddon 124) Later, after Talbot rejects Aurora,

she elides his period of ennui with

the admission, “I might fill chapters with the foolish sufferings of this young

man; but I fear he must have become very wearisome to my afflicted readers”

(165). Most revealingly, Braddon even attempts to dissuade criticisms of her

novel on the basis of genre: in the first chapter, she claims, “If this were a

very romantic story, it would be perhaps only proper for Eliza Floyd to pine in

her gilded bower, and misapply her energies in weeping for some abandoned

lover, deserted in an evil hour of ambitious madness. But as my story is a true

one…” (57) This explicit rejection of “romantic” clichés, and insistence on the

“truth” of the narrative, predicts later attempts in essays like Sala’s to

defend sensation by aligning it with realism. As Jennifer Phegley writes in her

article “‘Henceforward I Refuse to Bow the Knee to Their Narrow Rule’: Mary

Elizabeth Braddon’s Belgravia Magazine,

Women Readers, and Literary Valuation,” one of Braddon’s chief critical strategies

during the Belgravia period was to

redefine “her own brand of fiction as more realistic than realist novels”

(Phegley 152). Aurora Floyd’s

satirical treatment of “very romantic stories” suggests that this strategy was

already in place as early as 1862.

|

In

addition to making a case for the sensation novel as “more realistic than

realist novels,” Braddon also more explicitly upsets the cultural hierarchy through

her depictions of Aurora and Lucy. Aurora is described frequently with

references to (anti-)heroines from Shakespearean tragedies, particularly Lady

Macbeth, Desdemona, and the iconic Antony

and Cleopatra version of the historical queen. The association of these

dramatic figures with sensation fiction would later be made explicit in Belgravia: Sala, in his 1868 article “On

the ‘Sensational’ in Literature and Art,” argued for Shakespeare as an “arrant

sensational writer” and Desdemona in particular as a “sensational” character

(Sala 456). Lucy, meanwhile, is heavily associated with what might broadly be

called Victorian “high culture”: she is said to have “read Gibbon, Niebuhr, and

Arnold” (Braddon 68)—the latter referring to the educator Thomas Arnold, whose

son Matthew would famously define culture in his 1869 study Culture and Anarchy as “the best which

has been thought and said in the world” (Arnold 299). Despite the lofty

allusions used to describe Lucy, however, Aurora is ultimately determined to be

the more appealing character. As Talbot observes, “All that Aurora’s beauty

most lacked was richly possessed by Lucy. Delicacy of outline, perfection of

feature, purity of tint, all were there; but while one face dazzled you by its

shining splendour, the other impressed you only with a feeble sense of its

charms, slow to come and quick to pass away” (Braddon 93-94).

|

The

“dazzling” nature of sensation fiction was acknowledged even by one of its

harshest contemporary critics: Margaret Oliphant’s scathing “Novels” essay for Blackwood’s—the direct inspiration for

Sala’s rebuttals in Belgravia—admitted

that Aurora Floyd was a “very clever

story…well knit together, thoroughly interesting, and full of life” (Oliphant 263).

Such concessions, however, were tempered with a sense that a “thoroughly

interesting” novel was not necessarily a fulfilling or edifying one. By placing

her dazzling, sensational heroine at the center of a murder investigation,

Braddon at first seems to concede this point to her critics; but Aurora is not

guilty, and her ultimate absolution from guilt of James Conyers’ death solidifies

her place not as an irresistibly “beautiful fiend,” like Braddon’s earlier

protagonist Lady Audley, but as a new kind of literary ideal. Braddon may not

have “officially” engaged the critical discourse on sensation fiction until she

became editor of Belgravia in 1866;

however, these debates were clearly at the forefront of her mind even as her

literary identity was being solidified.

|

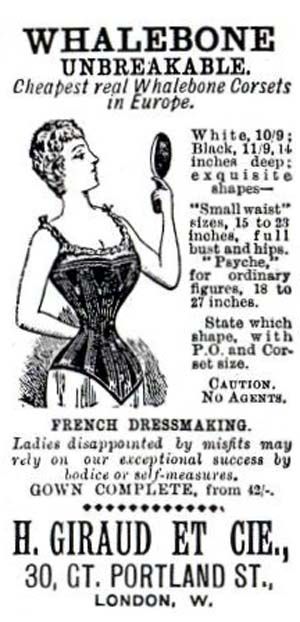

The Reining Fashion

By Deirdre Mikolajcik

In 1843, Mrs. Ellis published The Daughters of England, in which she admonishes her readers that “one of the greatest drawbacks to the good influence of society, is the almost unrivaled power of fashion upon the female mind” (126). Mrs. Ellis was not alone in her opinion; she was joined by “the largely male medical profession and the largely female dress reformists” (Summers 97). Despite many enemies, extreme fashions flourished during the nineteenth century, the most infamous of all being the corset. While less known than the corset, a second fashion trend also caused severe discomfort and health issues: the curb-bit and bearing rein for horses. While these fashions at first appear to have little in common, a closer examination reveals many similarities, including a pervasive, if unspoken, presence in Braddon’s Aurora Floyd.

In 1843, Mrs. Ellis published The Daughters of England, in which she admonishes her readers that “one of the greatest drawbacks to the good influence of society, is the almost unrivaled power of fashion upon the female mind” (126). Mrs. Ellis was not alone in her opinion; she was joined by “the largely male medical profession and the largely female dress reformists” (Summers 97). Despite many enemies, extreme fashions flourished during the nineteenth century, the most infamous of all being the corset. While less known than the corset, a second fashion trend also caused severe discomfort and health issues: the curb-bit and bearing rein for horses. While these fashions at first appear to have little in common, a closer examination reveals many similarities, including a pervasive, if unspoken, presence in Braddon’s Aurora Floyd.

|

In Aurora

Floyd, the corset is not specifically mentioned in the way Aurora’s “now

universal turban, or pork-pie” (Braddon 184) hat and her “diamond bracelet,

worth a couple hundred pounds” (79) are, likely because of its status as an

undergarment---an overt mention would have given Braddon’s detractors reason to

call her writing pornographic. Despite this, it is likely that Aurora was

corseted while she went about her daily activities, including riding. As late

as the 1890s, corset companies were advertising their wares in pictures of “competent

women exuberantly participating in…outdoor pursuits such as horse riding”

(Summers 177). For a fashion-conscious young woman such as Aurora, a corset

“beautifully decorated with ‘flossing’ or ‘fanning’ of shell-pink thread”

(Summers 156) against a black background would have been a desirable object.

Furthermore, during the time Braddon was writing, corsets were considered

important in denoting social class (Summers 7), an undercurrent in Braddon’s Aurora Floyd. A tightly

laced corset was “undergone for the purpose of lowering the subject’s vitality

and rendering her permanently and obviously unfit for work” (Petcovici 209).

|

|

Similar to the corset, the curb-bit and

the bearing rein, “two popular harnessing devices which held the horse’s

head

tightly erect, compelling the animal into contrived and painful postures

for

the purpose of appearances alone” (Dorré 157) were used extensively by

the

bourgeoisie. Like the human corset, which was known to cause death,

miscarriage, uterine prolapse, punctured lungs, the rupturing of

internal

organs, and open sores from broken stays, many horsemen and veterinarians

reported

that “excessive tight-reining of a horse damaged its windpipe and

significantly

shortened its life, in addition to purportedly causing severe

discomfort”

(Dorré 162).

The dangerous fashions of the day place

women and horses as mirrors of one another, especially in the language

used to

describe horses and women. Braddon describes Aurora as “pleasant a sight

as the

smooth greensward of the Knavesmire, or the best horse-flesh in the

county of

York” (202). Earlier, in her encounter with Steeve Hargraves, Aurora‘s

“cheeks

[are] white with rage, her eyes flashing fury” (193). In 1842 a similar

description appears in Penny Magazine:

“Her large fiery eye gleamed from the edge of an open forehead, and her

exquisite little head was finished with a pouting lip” (“Horses in the

East”

448), but this catalogue of features belongs to a “hot-blooded” (448)

Arabian

filly and not a human woman.

|

|

Within the controversies surrounding

fashion, the topic of women riding horses was hotly debated. For every

article

that claimed “it is not becoming in a gentle and modest Englishwoman to

be seen

careering across country” (“Six”) there is an article declaring that

“the English

lady in her saddle is a picture of dignity and grace” (“Lady”). This

debate,

unlike the debates over fashion, explicitly appears in Aurora Floyd

through the voice of John Mellish, who tells Aurora, “I

think the good old sport of English gentlemen was meant to be shared by

their

wives” (262) and the opposing side in Talbot Bulstrode who viewed her

love of

horses with horror at the thought of what such tastes could do to “the

heir of

all the Raleigh Bulstrodes” (79). While this is the only debate that

explicitly occurs in Aurora Floyd, the debates of female and

equine fashion, and the alignment of women and horses is eloquently

hinted at by

Braddon in descriptions of Aurora and notably in the fact that a

beautiful, primped,

polished, and trained filly bears Aurora’s name.

|

The London Review on Aurora Floyd

|

By Kristy Scherba

In "Aurora Floyd," the London Review, 1863, Aurora Floyd is the giant among bigamy novels, feeding the public a better executed plot than Lady Audley's Secret. Mary Elizabeth Braddon's novel Aurora Floyd is contrived with greater finesse through winding chapters of well woven intrigue. The critic feels Braddon’s talent is wasted, however, on bigamy and a disregard for decency, “piling on the agony,” and implores Braddon to lift her talent to a higher level of meaning in response to her readership. Aurora is viewed as a manly character who hates Conyers, the groom she runs away with, abuses Mellish, the man she marries, and within the year readily forgets the one who loves her, Talbot. The only connection she has with the groom is horses and dogs; she is a “masculine woman with heart but not lovable, and borders on repulsive” (149). Her marriage to Mellish is one of bigamous consolation; she consoles her guilt and repressed anger by bullying him; he loves his beautiful tigress and takes her fiery hostility like a deserving child. Braddon’s work produces sensations of romance with tawdry images that have a negative influence on young female readers and is detrimental to society: “[w]e cannot sympathize with those who select scenes of domestic misery and crime” (149). Although not accused of “willfully corrupting society,” the critic argues what purpose is to be gained by popularizing domestic suffering beginning with the “clandestine marriage of a young lady with her groom...making the heroine marry a rich Yorkshireman while she is still the groom’s wife...[then] the groom being subsequently opportunely shot"(149) while living happily ever after. Instead of filling the public with misdirected passion like the French novelists to whom Braddon subscribes, the critic suggests she trade cheap thrills with shock value for charming references to meaningful and elevated subjects, adding, “no ill nature intended” (149). |

Telling Tales and Pruning Roses

By Kristy Scherba

In "Miss Braddon At Home," by Mary Angela Dickens, 1897, Braddon is declared "household word par excellence," and her work is described as “ honest and wholesome.” Such adjectives were previously non-existent thirty five years ago; in fact, Braddon’s early work was ostracized as polluting the reader’s mind with shocking themes of bigamy that induced images of morbid excitement. In spite of earlier critics, books flew off the shelves faster than the printer’s ability to keep pace with unprecedented demand. By 1897, however, Dickens describes a much more domesticated figure: a Braddon who collects china plates, portrait masterpieces, and fine book bindings, and is particularly fond of dogs. Her favorite fox terrier, Sam, and a black poodle, Squib, lounge at leisure on the sofa when not accompanying Braddon on country walks.

In "Miss Braddon At Home," by Mary Angela Dickens, 1897, Braddon is declared "household word par excellence," and her work is described as “ honest and wholesome.” Such adjectives were previously non-existent thirty five years ago; in fact, Braddon’s early work was ostracized as polluting the reader’s mind with shocking themes of bigamy that induced images of morbid excitement. In spite of earlier critics, books flew off the shelves faster than the printer’s ability to keep pace with unprecedented demand. By 1897, however, Dickens describes a much more domesticated figure: a Braddon who collects china plates, portrait masterpieces, and fine book bindings, and is particularly fond of dogs. Her favorite fox terrier, Sam, and a black poodle, Squib, lounge at leisure on the sofa when not accompanying Braddon on country walks.

|

The critics' dislike of Braddon’s Aurora Floyd, was a

societal pruning of her literary art. In the end, however, excellence in

style and commitment to sensational writing won the critics over

worldwide. The image of Braddon, jumping through hoops of mockery like a

circus performer for profit, was replaced with flowery praise like

delicate rose buds in her hands. The fragrance still lingers in those

critical words falling like banished rose petals to the floor, swept up

flawlessly with her tiny hands, hands capable of handling horses and

carrying a whip. Braddon hints of pruning the critics in Aurora Floyd:

"It is fortunate for mankind that speaking daggers is often quite as

great a satisfaction to us as using them, and we can threaten very cruel

things without meaning to carry them out. Like the little children who

say, 'Won't I just tell your mother!' and the terrible editors who

write, 'Won't I give you a castigation'" (Braddon 349).

|

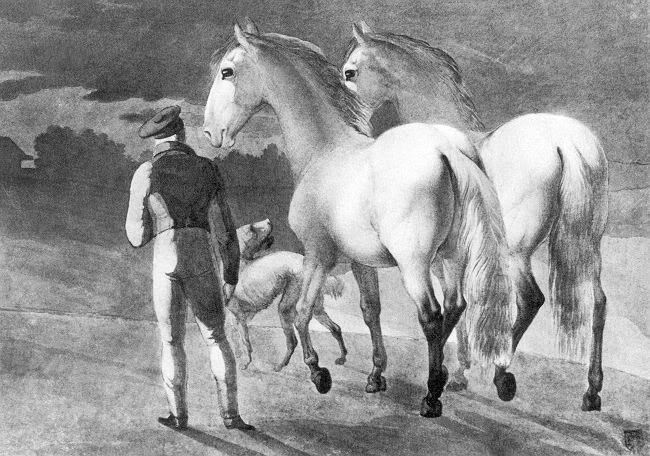

Jacques-Laurent Agasse's "Stable Boy with Two Grey Horses And A Dog"

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

|

In Jeni Curtis' "Pruning the Docile Body in Aurora Floyd,"

two opposite extremes are manifest as cousins whose social grooming

reveal natural and unnatural tendencies of passionate and dispassionate

natures:"the bright exotic is trimmed and pruned by the gardener's

merciless hand, while Aurora shot whither she would, and there was none

to lop the wandering branches of that luxuriant nature" (Braddon 61). As

women of Victorian times, Aurora is all that is forbidden; she is

running with the servants and horses, hunting, and frolicking in the

woods without a chaperone. She is riding with her groom, learning

unspeakable things of nature; her black hair uncoils like serpents,

signifying sexual urges. "You don't use that animal well, Aurora. A six

hours' ride is neither good for her or for you. Your groom should have

known better than to allow it" (Braddon 64).

|

Meanwhile, cousin Lucy is

repressed through societal constraint and remains passionless, docile

and dull. "Purity and goodness had watched over her and hemmed her in

from her cradle" (Braddon 94). A patriarchal stronghold pruned her to please

man, remain chaste, and represent man's image of woman as the angel of

the house. Procreation for his pleasure was the only justification for

sexual activity, dictated by domestic life. "The muslin folds of her

dress rose and fell with the surging billows; but, for the very life of

her, she could have uttered no better response to Talbot's pleading"

(Braddon 220). Lucy’s sexually repressed nature as the "hypocrite" buried a

burning, secret desire, snuffed out by societal control. For Lucy,

social education left her devoid of feeling; in effect, castrating her

sexuality by slicing off the freedom to feel. Lucy "bore her girlish

agonies, and concealed her hourly tortures, with the quiet patience

common to these simple womanly martyrs" (Braddon 102).

|

In contrast, Aurora

rejects an artificial life of adornment and embraces an unnatural

preoccupation with horses, running free like a wild mustang from a world

devoid of sensuality and passion; she is disinterested in feminine

things. "The diamond bracelet...lay in its nest of satin and

velvet...[s]he took the morocco-case in her hand, looked for a few moments

at the jewel, and then shut the lid of the little casket with a sharp

metallic snap" (Braddon 81). The female watchers act as social police,

exposing a blemish in Aurora’s past and dissuade Talbot from marrying

her; preserving his dispassionate nature apart from that "rare" and

"exotic" delight, he trades fiery passion for domesticity. "[S]o we

dismiss Talbot Bulstrode for a while, moderately happy, and yet not

quite satisfied," (Braddon 227) Talbot's ideal mate..."was some gentle and

feminine creature...some timid soul with downcast eyes...some shrinking

being; as pale and prim as the medieval saints..spotless as her own

white robes, excelling in all womanly graces and accomplishments, but

only exhibiting them in the narrow circle of a home"

(Braddon 86). Dispassionate Lucy becomes the perfect wife for Talbot, secure

in their domestic platitude of sexual indifference, while radiant and

beautiful Aurora rides..."across the moorland on her thorough-bred mare,

driving all the parish mad with admiration of her" (Braddon 102).

|

Ride this Train: A Negotiation of Space

By Marie DiFilippo

The secret of Aurora Floyd’s inescapable, bigamous situation had already been made “common property” (Braddon 431) by the time she decided to flee Mellish Park via railway without consulting her husband John Mellish. Upon her arrival at Doncaster, Talbot says uneasily, “I am sorry you came up to town alone, because such a step was calculated to compromise you” (431).

An article entitled "Loops and Parentheses" appeared in Temple Bar, August 1862, alongside the serialization of Aurora Floyd. This article compares the undulations of Victorian life to “loop-lines, or railway parentheses [that] have just flung themselves off the main road for a moment—just digressed into strange lands to see what they were like” (LEL 52). The author remarks these loop-lines which digress from the main line nonetheless return to their central point, resulting in new yet inclusive “life and motion and enterprise” (52).

Michel Foucault, in “Space, Knowledge, and Power,” similarly responds to “the social phenomena that railroads gave rise to” (243) during the nineteenth century. The accessibility of railways encouraged Europe to “establish a network of communication no longer corresponding necessarily to the traditional network of roads” (243). Mary Elizabeth Braddon saw that literature, too, must allow for loop-lines and shifts away from traditional and central forms of communicating.

The secret of Aurora Floyd’s inescapable, bigamous situation had already been made “common property” (Braddon 431) by the time she decided to flee Mellish Park via railway without consulting her husband John Mellish. Upon her arrival at Doncaster, Talbot says uneasily, “I am sorry you came up to town alone, because such a step was calculated to compromise you” (431).

An article entitled "Loops and Parentheses" appeared in Temple Bar, August 1862, alongside the serialization of Aurora Floyd. This article compares the undulations of Victorian life to “loop-lines, or railway parentheses [that] have just flung themselves off the main road for a moment—just digressed into strange lands to see what they were like” (LEL 52). The author remarks these loop-lines which digress from the main line nonetheless return to their central point, resulting in new yet inclusive “life and motion and enterprise” (52).

Michel Foucault, in “Space, Knowledge, and Power,” similarly responds to “the social phenomena that railroads gave rise to” (243) during the nineteenth century. The accessibility of railways encouraged Europe to “establish a network of communication no longer corresponding necessarily to the traditional network of roads” (243). Mary Elizabeth Braddon saw that literature, too, must allow for loop-lines and shifts away from traditional and central forms of communicating.

|

The year 1855 marked the removal of newspaper stamp

taxes. Popular short stories and novels, like Aurora Floyd, became

available through six shilling and two-shilling yellowback editions. These

periodicals were available in railway waiting rooms, allowing wider access to

contemporary literature. This availability opened doors, blurring a purity

division between high and low literature (Nemesvari and Surridge 13). George

Eliot would, in 1866, pervert this shift toward wider access by labeling

Braddon’s work as sensationalized, low “trash” (12). Critics like Eliot

attempted to colonize the new, ambiguous space Braddon’s genre occupied by not

only dragging her “private life [into] the glare of public scrutiny” (10), but

by fallaciously labeling her work as immoral and “unrealistically sordid,”

though it drew heavily from true, daily news reports (15).

|

|

Aurora Floyd’s own critics within the novel place

her private life under scrutiny and police the spaces she occupies. Mellish

Park in particular, Aurora Floyd’s haven, continually gets perverted,

disrupted, and reconstructed. When Aurora sneaks out of the home for a meeting

with blackmailing James Conyers, deceitful Mrs. Powell tells a servant Aurora

is already back in the house, and orders him to “shut all the windows, and

close the house for the night” (Braddon 271). Aurora is locked out of the

house. The narrator tells us, “This being done, all communication between the

house and the garden was securely shut off” (271). Mrs. Powell’s revulsion for

Aurora is characterized as a hate which “such slow, sluggish, narrow-minded

creatures always hate the frank and generous” (188). The shutting off of

communication at Mellish Park smacks of the practices of Braddon’s critics.

|

|

Of course, Mrs. Powell is only one of many

watchdogs who threaten Aurora’s space within the novel. She is the second

oppressor to be exiled by John Mellish, who first offers her the warning, “I

require no information respecting my wife’s movements from you, or from any

one. Whatever Mrs. Mellish does, she does with my full consent” (335). He also

declares to Powell, “I generally prefer the high road” (336) as opposed to low,

deceitful communication practices. In volume III, Mellish finally discharges

Powell, saying “I preferred telling you the plain truth,” (420) and does not

hesitate to pay her stipend dues.

|

|

Mellish Park, like a train station, is an important

networking space for Aurora. It offers her a sense of shared property ownership

and interests with her husband, at a time when conventional marriages were not

balanced. John and Aurora’s love is “mutual and reciprocal” (Schroeder and

Schroeder 96). Natalie and Ronald Schroeder argue, then, that Braddon endorses

unconventional marriages, without repudiating the traditional. Instead, Braddon

is suggesting “that conflicting models of marriage do not necessarily exclude

one another but can coexist” (104). Braddon saw her work as coexisting

alongside conventional Victorian models. She stated in a letter to Sir Edward

Bulwer Lytton, in 1863, “I want to serve two masters. I want to be artistic and

to please you. I want to be sensational, and to please Mudie’s subscribers”

(qtd. in Phegley Educating 110). Rather than choose the conventionally masculine Talbot

Bulstrode, Aurora does assert preference for John Mellish, to the point of

re-marrying him. This exemplifies Braddon’s endorsement of both a digression

from and a return to the “central line”, creating a marriage between two

seemingly contradictory states.

John Mellish is the husband who is able to “converse easily with employees, servants, and other commoners on a personal level” (Schroeder and Schroeder 91) and be fully aware of a patriarchal structure which governs Victorian life. The narrator says, “John Mellish was entirely without personal pride; but there was another pride which was wholly inseparable from his education and position, and this was the pride of caste. He was strictly conservative” (Braddon 412) and that "John Mellish submitted himself to the indisputable force of those ceremonial laws which we have made our masters” (414). John Mellish, like the railway, interacts with castes and undulating narratives both high and low. Like Braddon and Aurora, he attempts to negotiate a space in between where plain truth can be experienced, a new central point or “high road” inclusive of diverging loop-lines. |

Sources

Arnold, Matthew.

Culture and Anarchy: An Essay in

Political and Social Criticism; and Selections. Minneapolis: The H.W.

Wilson Company, 1903.

Blake, Peter, and Barbara Onslow. "Temple Bar(1860-1906)." C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. ProQuest, 2009.

Braddon, Mary Elizabeth. Aurora Floyd. Broadview Literary Texts. Richard Nemesvari and Lisa Surridge, eds. Ontario: Broadview Press, 1998.

Curtis, Jeni. “The ‘Espaliered’ Girl: Pruning the Docile Body in Aurora Floyd.” Beyond Sensation: Mary Elizabeth Braddon in Context. Eds. Marlene Tromp, Pamela K. Gilbert, and Aeron Haynie. New York: State U of NY Press, 2000. 77-92

Dickens, Mary Angela. "Miss Braddon at Home." The Windsor Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly for Men and Women 6 (Jun 1897): 415-418.

Dorré, Gina Marlene. "Horses and Corsets: "Black Beauty," Dress Reform, and the Fashioning of the Victorian Woman." Victorian Literature and Culture 30.1 (2002): 157-78.

Ellis, Mrs. Sarah. The Daughters of England, Their Position in Society, Character, and Responsibilities. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1843.

Foucault, Michel. “Space, Knowledge, and Power.” The Foucault Reader. New York: Pantheon, 1984: 239-256.

Hatton, Joseph. “Miss Braddon at Home. A Sketch and an Interview.” London Society: a Monthly Magazine of Light and Amusing Literature for the Hours of Relaxation. 53.313 (Jan 1888) 22-29.

Holland, Clive. "Miss Braddon; The Writer and her Work." The Bookman: 42, 250 (July 1912):pp. 150-157.

“Horses in the East and Their Treatment.” Penny Magazine 11 (1842): 447-48.

L, E L. "Loops and Parentheses." Temple Bar Aug. 1862: 52-60.

"Lady and Her Horse, The; being Hints Selected from various Sources, and Compiled into a System of Equitation.-the Gentleman and His Horse; being Selections from the Works of Boucher, Nolan, Richardson, and Other Authors on Horsemanship." The Athenaeum.1605 (1858): 133-4.

Nemesvari, Richard and Lisa Surridge, eds. “The ‘Sensational’ Life of M.E. Braddon.” Aurora Floyd. By Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Ontario: Broadview, 1998.

Oliphant, Margaret (uncredited). “Novels.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 102.623 (Sep. 1867): 257-280.

Petcovici, Tania. "Victorian Fashion--An Issue of Female Subjugation." British and American Studies 10 (2004): 207-15.

Phegley, Jennifer. Educating the Proper Woman Reader. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2004.

---. “‘Henceforward I Refuse to Bow the Knee to Their Narrow Rule’: Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Belgravia Magazine, Women Readers, and Literary Valuation.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 26.2 (2004): 149-171.

---"Cornhill Magazine(1860-1975)." C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. ProQuest, 2009.

Sala, George Augustus. “On the ‘Sensational’ in Literature and Art.” Belgravia: A London Magazine 4 (Feb. 1868): 449-458.

--- "The Cant of Modern Criticism."Belgravia: A London Magazine4 (Nov. 1867): 45-55.

Schroeder, Natalie and Ronald A. Schroeder. “Aurora Floyd: Constructing an Alternate Model of Companionate Happiness.” From Sensation to Society: Representations of Marriage in the Fiction of Mary Elizabeth Braddon, 1862-1866. Newark: University of Delaware, 2006.

“Six Reasons Why Ladies Should Not Hunt.” The Field, 15 April, 1854.

Summers, Leigh. Bound to Please: A History of the Victorian Corset. New York: Berg, 2001.

Blake, Peter, and Barbara Onslow. "Temple Bar(1860-1906)." C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. ProQuest, 2009.

Braddon, Mary Elizabeth. Aurora Floyd. Broadview Literary Texts. Richard Nemesvari and Lisa Surridge, eds. Ontario: Broadview Press, 1998.

Curtis, Jeni. “The ‘Espaliered’ Girl: Pruning the Docile Body in Aurora Floyd.” Beyond Sensation: Mary Elizabeth Braddon in Context. Eds. Marlene Tromp, Pamela K. Gilbert, and Aeron Haynie. New York: State U of NY Press, 2000. 77-92

Dickens, Mary Angela. "Miss Braddon at Home." The Windsor Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly for Men and Women 6 (Jun 1897): 415-418.

Dorré, Gina Marlene. "Horses and Corsets: "Black Beauty," Dress Reform, and the Fashioning of the Victorian Woman." Victorian Literature and Culture 30.1 (2002): 157-78.

Ellis, Mrs. Sarah. The Daughters of England, Their Position in Society, Character, and Responsibilities. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1843.

Foucault, Michel. “Space, Knowledge, and Power.” The Foucault Reader. New York: Pantheon, 1984: 239-256.

Hatton, Joseph. “Miss Braddon at Home. A Sketch and an Interview.” London Society: a Monthly Magazine of Light and Amusing Literature for the Hours of Relaxation. 53.313 (Jan 1888) 22-29.

Holland, Clive. "Miss Braddon; The Writer and her Work." The Bookman: 42, 250 (July 1912):pp. 150-157.

“Horses in the East and Their Treatment.” Penny Magazine 11 (1842): 447-48.

L, E L. "Loops and Parentheses." Temple Bar Aug. 1862: 52-60.

"Lady and Her Horse, The; being Hints Selected from various Sources, and Compiled into a System of Equitation.-the Gentleman and His Horse; being Selections from the Works of Boucher, Nolan, Richardson, and Other Authors on Horsemanship." The Athenaeum.1605 (1858): 133-4.

Nemesvari, Richard and Lisa Surridge, eds. “The ‘Sensational’ Life of M.E. Braddon.” Aurora Floyd. By Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Ontario: Broadview, 1998.

Oliphant, Margaret (uncredited). “Novels.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 102.623 (Sep. 1867): 257-280.

Petcovici, Tania. "Victorian Fashion--An Issue of Female Subjugation." British and American Studies 10 (2004): 207-15.

Phegley, Jennifer. Educating the Proper Woman Reader. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2004.

---. “‘Henceforward I Refuse to Bow the Knee to Their Narrow Rule’: Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Belgravia Magazine, Women Readers, and Literary Valuation.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 26.2 (2004): 149-171.

---"Cornhill Magazine(1860-1975)." C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. ProQuest, 2009.

Sala, George Augustus. “On the ‘Sensational’ in Literature and Art.” Belgravia: A London Magazine 4 (Feb. 1868): 449-458.

--- "The Cant of Modern Criticism."Belgravia: A London Magazine4 (Nov. 1867): 45-55.

Schroeder, Natalie and Ronald A. Schroeder. “Aurora Floyd: Constructing an Alternate Model of Companionate Happiness.” From Sensation to Society: Representations of Marriage in the Fiction of Mary Elizabeth Braddon, 1862-1866. Newark: University of Delaware, 2006.

“Six Reasons Why Ladies Should Not Hunt.” The Field, 15 April, 1854.

Summers, Leigh. Bound to Please: A History of the Victorian Corset. New York: Berg, 2001.

Artwork

Agasse, Jacques-Laurent. Stable Boy with Two Grey Horses And A Dog. 1837. Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Anderson, Paul. Castleshaw Lower Reservoir. 2007. Geograph, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Barber, John J. Jam O'Shanter. 1866. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Dunn, Henry Treffry. Dante Gabriel Rossetti Reading Proofs of Sonnets and Ballads to Theodore Watts Dunton in the Drawing Room at 16 Cheyne Walk, London. 1882. Pre-Raphaelites at Home, Watson-Giptill Publications. Wikimedia Commons.

Frith, William Powell. Mary Elizabeth Maxwell (née Braddon). Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

"'Gag' Bearing Rein, The." Illustration, from Rev. G. J. Woods, "The Horse and His Owner," Good Words 22 (1881): 640.

Giraud Company Newspaper Advertisement 1880's. Advertisement. Wikimedia Commons.

Morisot, Berthe. Le Berceau. 1873. Oil. Deutsch, Wiege. Wikimedia Commons.

Pedani, Matteo. Cammeo su conchiglia raffigurante testa femminile allegoria dell'autunno. 2006. Photograph. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Pettie, John. Two Strings to her Bow. 1882. Oil. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Rosen, Jan. Horsewoman. 1882. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Temple Bar. 2011. Photograph. www.rookebooks.com. Wikimedia Commons.

Vail, J.P. Seated Woman with Large Black Dog. 1875. Photograph. George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

"Waiting for Friends at Henley Station." Cartoon. Illustrated London News 12 July 1894. Wikimedia Commons.

Whishaw, Francis. "Railways in the South East of England in 1840." Map. The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co., 1840. Wikimedia Commons.

Anderson, Paul. Castleshaw Lower Reservoir. 2007. Geograph, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Barber, John J. Jam O'Shanter. 1866. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Dunn, Henry Treffry. Dante Gabriel Rossetti Reading Proofs of Sonnets and Ballads to Theodore Watts Dunton in the Drawing Room at 16 Cheyne Walk, London. 1882. Pre-Raphaelites at Home, Watson-Giptill Publications. Wikimedia Commons.

Frith, William Powell. Mary Elizabeth Maxwell (née Braddon). Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

"'Gag' Bearing Rein, The." Illustration, from Rev. G. J. Woods, "The Horse and His Owner," Good Words 22 (1881): 640.

Giraud Company Newspaper Advertisement 1880's. Advertisement. Wikimedia Commons.

Morisot, Berthe. Le Berceau. 1873. Oil. Deutsch, Wiege. Wikimedia Commons.

Pedani, Matteo. Cammeo su conchiglia raffigurante testa femminile allegoria dell'autunno. 2006. Photograph. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Pettie, John. Two Strings to her Bow. 1882. Oil. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Rosen, Jan. Horsewoman. 1882. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Temple Bar. 2011. Photograph. www.rookebooks.com. Wikimedia Commons.

Vail, J.P. Seated Woman with Large Black Dog. 1875. Photograph. George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

"Waiting for Friends at Henley Station." Cartoon. Illustrated London News 12 July 1894. Wikimedia Commons.

Whishaw, Francis. "Railways in the South East of England in 1840." Map. The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co., 1840. Wikimedia Commons.