British Visual and Textual Rhetoric on Slavery

JessN

British Visual and Textual Rhetoric on Slavery

by Jessica Nottingham, Caroline Williams and Raenesha Green

The

Transatlantic

Slave Trade was established as a barter system that compromised

the lives and future of African natives. Over four hundred years of

human

trafficking and enslavement ensued before the immoral institution of

slavery

was legally brought to an end. During the latter part of those

centuries, an abolitionist movement began as people finally began to

open their eyes to the brutality and

unethical mistreatment of the African race. With the rise in voice of

abolitionists throughout Britain in the late eighteenth century, came

also an

increase in rhetoric from writers of Romanticism. One of such was the

talented

William Blake, some of whose work expresses what was considered at the

time to

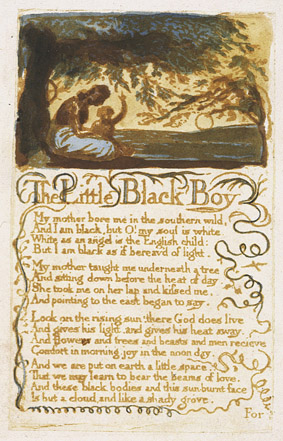

be radical views and abolitionist beliefs. Displayed in Figure 1,Blake’s “Little Black Boy” is an

example of his work that supported the abolitionist agenda and sympathized with

those many souls that fell victim to the slave trade. Lisa Parker’s analysis of

Blake’s “Little Black Boy” in her master's thesis asserts that many scholars

tend to overlook this poem as a work of abolition. However, Parker further

examines Blake’s poem and suggests that,

|

Figure 1. “The Little Black Boy” poem and

engraving by William Blake. The image depicts

the verses in the second stanza of the poem. The stanza is as follows, My mother

taught me underneath a tree The mother sits on the southern plains underneath a tree,

presumably somewhere in Africa, with her child on her lap, the two of them

surrounded by the light of the rising sun. The scene is a familiar one where a

mother passes on what she knows to her child, showing her affection by holding

him on her lap and kissing him. The child pointing up toward the heavens

represents childlike curiosity as he looks to his mother to show the trust

and belief he has in her. This displays a scene that is no different between

mother and child of any race. The shining, rising sun represents how the sun,

God’s light, shines upon them like it does upon anyone else. |

A Brief history of the poet WIlliam Blake

Although

Blake and his comrades supported the fight against slavery

and labor issues, one political cartoonist appeared to underestimate the

severity of slavery as seen in Figure 2, the cartoon entitled Slavery. Freedom. In this cartoon, the viewer’s eye is first drawn

to the large man standing behind a large cask, of wine, perhaps. One may

observe that he symbolizes wealth and fortune, and therefore can relate neither

to the factory worker to the left, nor to the slaves on the right. His dialogue,

though, appears to be sympathetic to the slaves as he tells the factory worker

not to despair, because he has all these rights that the slaves have not been

fortunate enough to experience. Ironically enough, some of these rights apparently refer to the Reform Bill or Act, passed in 1832, which called for

Parliamentary reform and extended the voting rights. The UK

Parliament website, however, explains that though this Act revealed a

potential for change, many of the men were still not eligible to vote because they did not meet the “property qualifications.” The Fat Man in the cartoon also mentions the Magna Carta, which basically states that nobody, including

the Crown, is above the law. Though these are significant acts of political

reform, they do little to nothing to help the conditions of factory workers and their families. The dialogue between the worker and his wife gives the implication

that no matter how hard one works, starvation and struggle are almost guaranteed.

The worker then states that he would basically have to “draw a cart harness’d

like a beast and get fed by the parish” in order to receive sustenance. Below

the factory family is a pile of tax forms that indicate the worker feels all he does is work to pay taxes. Beneath the left part of the

picture is the word “slavery,” which imparts the view that the factory worker is

an example of “white slavery.” On the opposing side of the cartoon is a family

of black slaves, whose portrayal implies that they do not have to worry

about hunger. As the father asks his son, “A ah pikaninny you eat yam yam you

belly full?”, the artist denotes the family as a unit, happy and fed, with fellow slaves

dancing in the background. Beneath the slave family is the word “freedom.” The

cartoon may depict what many onlookers witnessed at the first sight of

slavery: a merry people seemingly with no qualms about their situation. But that

concept is misconstrued as it is only an outside perception of a deeper,

suppressed struggle. Many slaves had the appearance of outward happiness due to

the fear of consequences for expressing their true inner turmoil. In the middle

of the picture is a spread of slavery books, anti-slavery reports and

propaganda, indicating that the artist thought more

time and effort were put toward the abolishment of slavery, than concern

and care toward improving the conditions of lower class British citizens.

What the artist of this cartoon does not represent is the reality of the

Transatlantic Slave Trade. Millions of Africans were tragically affected by the

mass casualties that occurred aboard slave ships in the Middle Passage. Back then, as now, and even in times before,

people tended to be blind to injustice.

|

Figure 2. Slavery. Freedom. This

image demonstrates the fact that there was more than one type of slavery taking

place in the British Empire. While Africans were being exploited and treated

cruelly, so were the lower classes who worked in the factories, to a

much lesser degree. However, the point stands that they too were in need of

freedom. The papers below the barrel, on which the fat (wealthy) preacher/

abolitionist advocates the abolishment of slavery, show that slavery

was on the forefront of everyone’s mind, while the similar plight of others

was completely ignored . On the left is the English worker, exhausted and

barely making ends meet to support his family. On the right is a depiction of

what many (wrongly) believed slaves’ lives were like: well-fed, happy, dancing,

and without a care in the world. The creator of the image disregarded the fact

that slaves owned nothing and were often punished

harshly for little to no reason. The artist’s intent was to shift focus away

from freeing slaves to helping free Englishmen from a type of slavery that he

felt was closely related to serfdom. However, there were Romantic poets like

Blake who recognized the seriousness of both slavery and Britain’s labor

conditions and did their best to shed light on both without discarding one for

the other. |

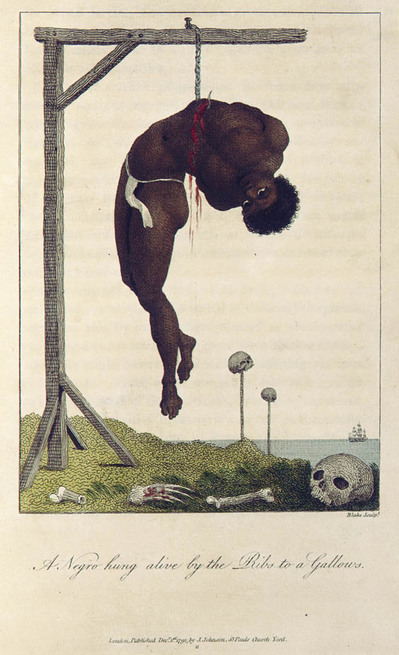

Even

though the enslavement of Africans had been hundreds of years ongoing, many

British did not fully comprehend the cruelty and brutality of slavery until

they came face to face with freed slaves and others with firsthand accounts. According

to Parker, one of Blake’s first experiences with the brutality of

slavery came from his work on the engravings for Captain John Gabriel Stedman’s

A Narrative, of Five Years’ Expedition,

Against the Revolting Negroes of Surinam. As shown in Figure 3, Blake’s graphic work displayed

his sense of compassion for those that suffered the harshness of slavery (Parker 3-4).

Blake passed away before he could bear witness to any further progress toward the abolition of slavery and the regulation of factory laws and conditions. In an

online article, “On the Sacramental Test Act, the Catholic Relief Act, the

Slavery Abolition Act, and the Factory Act,” Elsie B. Michie discusses how headway

was made in 1833, when Parliament passed bills to abolish slavery and regulate

child labor laws. Both these acts involved negotiation: slaves were

mandated to a 12 year apprenticeship before obtaining freedom, and instead of improved conditions for

all factory workers, only children began to see some relief. In the years that

followed, more improvements came as more advocates continued a campaign for equality and regulation reform. With the help of literature, social issues such

as slavery and labor laws were brought to the surface. “The Little Black

Boy,” along with other abolitionist poetry, helped to make the British more

aware of the inhumanity and injustice of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

|

Figure 3."A Negro hung alive by the Ribs to a Gallows," an engraving by William Blake for John Gabriel Stedman's Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, Object 2 (Bentley 499.2) Blake successfully blends his visions of slavery with Stedman’s to portray the cruel realities of slavery. The slave in the picture assumes an almost Christ-like position with the rack representative of the cross. As noted by Gupta, “the large eyes of the slave follow a similar pattern to Western depictions of Christ.” The skulls and bones around and behind the slave definitely indicate he is only one of many who have been subjected to such cruelties. In the distance is a ship that possibly represents the British Empire and how far removed it was from atrocities taking place under its reign, although that did not make Britain any less responsible for this cruel and brutal behavior. |

Works Cited

Adi,

Hakim, Dr. “Africa and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.” BBC. N.p. 5 October 2012. Web. 23 November

2014.

Blake, William. “The Little Black Boy.” The William Blake Archive. Ed. Eaves, Morris, Robert Essick, and Joseph Viscomi. Lib. Of Cong. Web. 26 Nov. 2014

Blake, William, ill. John

Gabriel Stedman, Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam,

object 2 (Bentley 499.2) "A Negro hung alive by the Ribs to a Gallows." The William Blake Archive. Ed. Eaves, Morris, Robert Essick, and Joseph Viscomi. Lib. of Cong. Web. 22

Nov. 2014

Gupta, Anukriti. “Ideas of Slavery and Racism in the Poems of William Blake.” Academia.edu. Web. 13 Nov. 2014.

Michie,

Elsie B. “On the Sacramental Test Act, the Catholic Relief Act, the Slavery

Abolition Act, and the Factory Act.”

BRANCH: Britain, Representation and

Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino

Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism

and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 23 November 2014.

Mitchell, Paul. “William Blake: A Radical Visionary." World Socialist Web Site. 2001. Web. 24 Nov. 2014.

Parker,

Lisa Karee, "A World of Our Own: William Blake and Abolition."

Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006.

Web. 23 November 2014.

“The Reform Acts and

Representative Democracy.” UK Parliament

Website. Web. 23 November 2014.

Slavery.

Freedom. 1832. Lithograph print. Lib. of Cong., Washington, D.C. PC 1-17219. Web. 23 November

2014.