NINES Peer-Reviewed Essays content in NINES is protected by a Creative Commons License.

D.G. Rossetti’s “The Burden of Nineveh”: Further Excavations

Pages:

«Previous page

1Page 1

2Page 2

3Page 3

4Page 4

You are here 5Page 5 EndmatterEndmatter »Next page

You are here 5Page 5 EndmatterEndmatter »Next page

536

Rossetti’s changes to the 1850 “Jonah” stanza (number 6) for publication in Oxford/Cambridge are less extensive, the most significant being the replacement of “grey stones” with “London stones,” a move that foregrounds the geographical exile of the Assyrian bull-god as well as the continuities between ancient and modern empires. The shadow on the stones is simultaneously a marker of alienation and of belonging, an idea the poem explores in some detail. Also interesting is the specificity of “fifteen days of flame” in the 1856 version, a number reported in the history of Sardanapalus by the Hellenistic author Athenaeus (in his Deipnosophistae) and likely picked up in other accounts.@The Deipnosophists, 5.389 (bk. xii, 529). Interestingly, Athenaeus also presents Sardanapalus as “combing purple wool” (5.387) with his concubines, a possible source of the languid weaving of the “purple-mouthed” maidens in Rossetti’s poem. His interest piqued by the Nineveh bull, Rossetti seems to have done some further reading on Assyrian history. As Frederick Bohrer, Shawn Malley, and others have shown, there was certainly plenty of such material published in England in the 1850s, in the wake of A.H. Layard’s discoveries. Finally, the “scorched” and “shrivelled” language describing Nineveh in 1850 is toned down to “smoulder’d” in the first published version and thereafter.

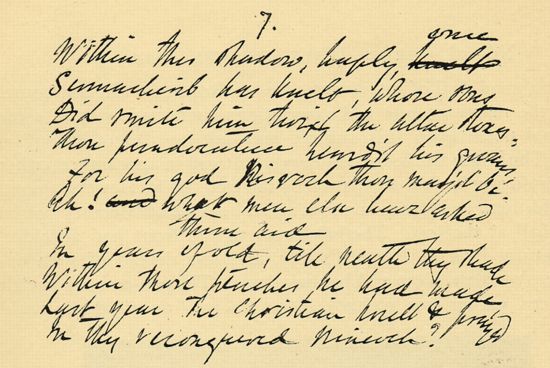

Marillier calls the second of the manuscripts an “interpolation on the opposite page of the manuscript book – or a blank portion of the same page,” and he dates it to “some succeeding year not later than 1856” (221). That seems correct: it looks to be a stanza added during a phase of revision, perhaps as Rossetti was preparing the poem for publication in the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, but more likely earlier, given its wide variation from the 1856 text. For example, because it is numbered “7,” we know that it was copied out as part of the original manuscript sequence, before the omission and condensation that Rossetti mentions above. The following is a transcription of the manuscript (see figure 2):

7.

Within his shadow, haply, knelt once

Sennacherib has knelt, whose sons

Did smite him twixt the altar stones:

Thou peradventure heard’st his groans,

For his god Nisroch thou may’st be.

Oh! and what men in war asked thine aid

In years of old, till neath thy shade

Within those trenches he had made,

Last year the Christian knelt & pray’d

In thy reconquered Nineveh?

Within his shadow, haply, knelt once

Sennacherib has knelt, whose sons

Did smite him twixt the altar stones:

Thou peradventure heard’st his groans,

For his god Nisroch thou may’st be.

Oh! and what men in war asked thine aid

In years of old, till neath thy shade

Within those trenches he had made,

Last year the Christian knelt & pray’d

In thy reconquered Nineveh?

By way of immediate comparison, here are the lines from the 1856 Oxford/Cambridge version:

Within thy shadow, haply, once

Sennacherib has knelt, whose sons

Smote him between the altar-stones:

Or pale Semiramis her zones

Of gold, her incense brought to thee,

In love for grace, in war for aid; . . . .

Ay, and who else? . . . . till 'neath thy shade

Within his trenches newly made

Last year the Christian knelt and pray'd—

Not to thy strength—in Nineveh. (lines 51-60)

Sennacherib has knelt, whose sons

Smote him between the altar-stones:

Or pale Semiramis her zones

Of gold, her incense brought to thee,

In love for grace, in war for aid; . . . .

Ay, and who else? . . . . till 'neath thy shade

Within his trenches newly made

Last year the Christian knelt and pray'd—

Not to thy strength—in Nineveh. (lines 51-60)

The manuscript version has “Nisroch” (the Assyrian god in whose temple Sennacherib was murdered, according to Isaiah 37:38) and the groans of Sennacherib; the revised text presents instead Semiramis and offerings for grace in love, a perceptible softening of the imagery. In addition, Rossetti may have read in Layard’s 1854 Popular Account of the Discoveries At Nineveh that Nisroch was a bird-headed, winged figure (not a bull with a human head); Layard discovered such images in Sennacherib’s palace, and identified the bird-men (somewhat dubiously) with the Biblical Nisroch (47). Finally, the manuscript’s “reconquered Nineveh” is replaced by the more reticent “Not to thy strength,” which downplays the issue of imperial archaeology that the manuscript reading (“reconquered Nineveh”) raises explicitly. These and other variants make both Marillier manuscripts particularly valuable windows onto this early stage of the poem’s composition.

Following its August 1856 publication in the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, “The Burden of Nineveh” appeared in New York, in the May 1858 issue of The Crayon, an art periodical edited by William Stillman and John Duran from 1855-1861.@For more on The Crayon, see http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/n1.c9.raw.html. A note in the Rossetti Archive indicates that it was “picked up and reprinted” but this is not strictly accurate, as the poem had undergone another stage of revisions for this new publication. Indeed, the significance of The Crayon versions of Rossetti’s works has generally remained unrecognized. “The Burden of Nineveh” was sent to editors of The Crayon by one of the Pre-Raphaelite circle (perhaps William Allingham or even William Michael Rossetti), who informs readers in a headnote that the poem (along with “The Blessed Damozel” and “The Staff and Scrip,” also printed in The Crayon) had

appeared some months ago in an English magazine, which was published

for a year, never reaching a large circulation, and which is now

extinct [i.e. The Oxford/Cambridge Magazine]. It contained the writings

of some of those younger men who will win fame for themselves, if they

live, and who, if they die before fame comes to them, will have had

what is better than fame. These poems show such power of expression,

such depth of sentiment, such force of imagination, as are rarely found

in modern verse. They were written by one of the leaders of the

Pre-Raphaelite school in painting, and they are an interesting

illustration of the imaginative tendencies, and of the tone, the

thought and feeling which pervade that school. (Crayon 5.95)

Coming thus directly from the Rossetti circle, these texts are more than simple tear-sheets from the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine. It is true that The Crayon texts of the “The Blessed Damozel” and “The Staff and Scrip” show only minor, incidental variants not traceable to Rossetti. But in the cases of “The Burden of Nineveh” and “Hand and Soul” – which was also printed in The Crayon in 1858 – Rossetti transmitted texts that he had revised in small ways. “Hand and Soul,” for example, which had first been printed in The Germ in 1850, has one additional sentence in The Crayon (printed in bold below), an elaboration of the anecdote of Bonaventura (revealed using JuXta software):

But one night, being in a certain company of ladies, a gentleman that was there with him began to speak of the paintings of a certain youth named Bonaventura, which he had seen in Lucca; adding that Giunta Pisano might now look for a rival. When Chiaro heard this, the lamps shook before him, and the music beat in his ears and made him giddy. He rose up, alleging a sudden sickness, and went out of that house with his teeth set. And the same night he wrote up inside his door the name of Bonaventura, that it might stop him when he would go out. (Crayon 5.273)

This addition finds its way (in slightly altered form)@In the 1869 privately-printed pamplet, the line reads, "And, being again within his room, he wrote up over the door the name of Bonaventura, that it might stop him when he would go out"(6). See http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/46p-1849.1869.mcgann.rad.html into all later printings of the tale, and has been assumed to have been added when Rossetti made revisions prior to the 1869 Penkill proofs. Its presence here offers more evidence that The Crayon was not simply copying published texts but working from material with authoritative, unpublished emendations.