How "A Musical Instrument" Embodies Divinity and Morality

Leah Rifkin and Sarah Cooper

Ryerson University

1320

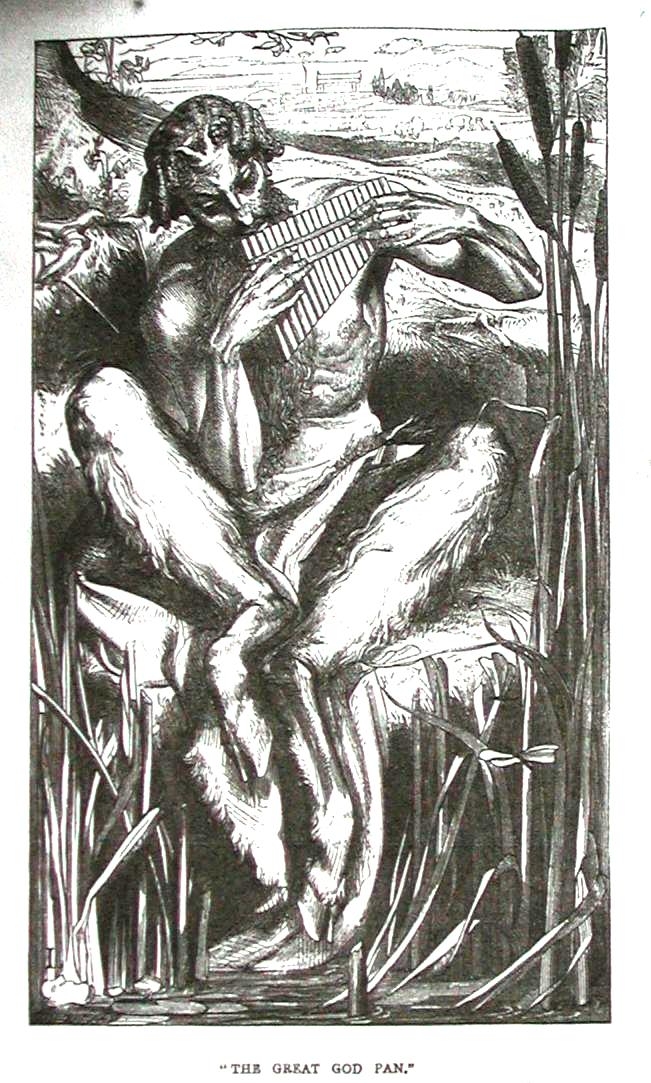

The Great God Pan

Frederick Leighton

|

An article by Elizabeth Prettlejohn@Prettlejohn, Elizabeth. "Morality versus Aesthetics in Critical Interpretations of Frederic Leighton, 1855-75." The Burlington Magazine 138.1115 (1996): 79-86. JSTOR. Web. 24 Mar. 2011. details the motivations for Frederick Leighton’s art. It discusses the idea of rating art based on being “purely artistic” rather than riddled with moral messages. Critics say there is a lack of expression in Leighton's work that contradicted the structure of expression as the base for communicating a message to the viewer. However, the article argues that he intentionally did not follow this common model because he wanted to depict a character's "social status, their psychological or emotional states, or their moral natures". Most of Leighton's pieces illustrate women, and his wood engraving of Pan can also be considered a subject of the female sex in terms of what the god symbolizes in the poem. True, he has a destructive nature that is inherently masculine in terms of 19th century roles because he smashes, destroys, and kills. He hacks and hews with a “hard bleak steel” and puts holes in it as he whittles is reed. The last line of the fifth stanza describes him blowing in “power by the river” which is distinctively masculine imagery with no softness to be found. |

|

But in the sixth stanza, the perspective on his actions has been subverted. He becomes a feminine embodiment through the repeated emphasis on the sweetness of his music. He is creating, giving life, which is traditionally considered the role of woman. He revives the dying lilies and entices the dragonfly to return. The enticing, soft, sweet, life-giving woman is the epitome of feminine character. It is this picture which Leighton has chosen to illustrate. Much like the poem itself, Pan is a seemingly masculine figure with some feminine undertones. While the image is of a very masculine body with well-defined muscles, strong facial features and a bushy beard, the body language suggests otherwise. His posture denotes a certain softness; his legs poised in a loose position and hands softly focused on producing the regenerative music. It is not the devastation that Leighton chooses to focus on but rather the moment of revival.

|

|

Some critics say that Leighton believed that neither music nor painting are proper tools for teaching morals. Art may have "an awakening influence, an ethos of its own, a power of intensification, and a suggestiveness through association which aid those higher moods of contemplation that are as edifying in their way as direct moral teaching”.@"Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics." Musical Times and Singing Class Circular Jan. 1882: 15-17. C19 Index. Web. One can pay close attention to Leighton's wood engraving of "The Great God Pan" to establish if it was successful in portraying the moral teachings which E.B. Browning’s poem explores. The poem presents morals and lessons about the divine importance of music (as an art form) and poetry (as a literary form) to Victorian society. Both are a means to express one’s thoughts and emotions concerning the issues of the time.

Indeed, issues such as the feminist movement went hand in hand with the art and culture of the time. Reading and writing were empowering acts for the 19th century woman who had traditionally been kept to the side with matters regarding education. As a female author, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s work is viewed with a separate kind of scrutiny. Her works were certainly feminist, and reading into the gender roles embodied within "A Musical Instrument" one will find a reflection of the times. Distinctly masculine with a feminine touch, Pan shows what the women of the 19th century were capable of and what women’s suffrage could do for society. |