The Portrayal of the Cloistered Victorian Woman

Shabnam Yusufzai and Sue Chun

1373

|

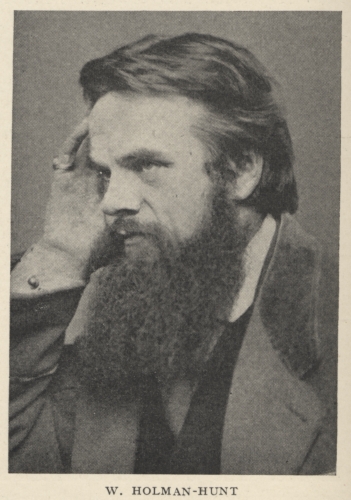

William Holman Hunt’s fascination with Tennyson’s poem, The Lady of Shalott, instigated his series of representations of the Lady.@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 235. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

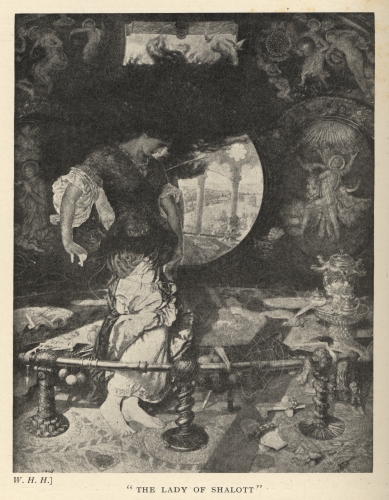

Hunt had sketched a variety of Shalottian subjects in 1850, depicting the Lady in several positions at different stages in her life. Amongst these many sketches, one particular illustration - his "Study for the 'Lady of Shalott" - captures the critical moment of Tennyson’s poem when the Lady looks directly out into the world and realizes her deadly fate: “Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack’d from side to side; “The curse has come upon me,” cried The Lady of Shalott.”@Alfred Tennyson, "The Lady of Shalott ENG 633: 19th Century Literature and Culture II Course Reader, ed. Lorriane Janzen (Toronto: Ryerson University, 2011)160-162. Hunt’s depiction of this moment consists of the Lady physically entangled in the threads of her own tapestry, although this is a moment absent in Tennyson’s narrative. It is evident that the concept of this 1850 illustration has lived on through and within his subsequent illustrations including Hunt’s 1857 Moxon wood engraving, Lady of Shalott, and his final 1905 oil on canvas painting, Lady of Shalott. Although the Lady’s physical entanglement remains constant throughout his later illustrations, Hunt had also made important changes throughout his various versions. A significant adjustment can be seen with the lady’s hair, which is tied at the back of her neck in Hunt’s 1850 sketch, but is later transformed into long flowing hair that, according to Tennyson, looks as though it were “wildly tossed about as if by a tornado”@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 235. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. in his 1857 and 1905 versions of the illustration. It is interesting to note that although Tennyson had confronted Hunt about this element in his 1857 moxon illustration of the Lady, and disapproved of it, Hunt still included it in his final 1905 illustration. |

|

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood regarded Tennyson as one of their favourite poets.@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.

Within two decades since the publication of Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott”, the poem had a great aesthetical impact on the Brotherhood@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. . Despite this fact, through short conversation between Hunt and Tennyson, Tennyson’s disapproval of Hunt’s depiction of the Lady is evident as he states that “The illustrator should always adhere to the words of the poet!”@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. Hunt – along with the Brotherhood – however, was not simply illustrating when painting scenes of a poem. His painting is in itself a new poem created within the context of Tennyson’s verse@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. . John Ruskin, a famous art critic who heavily backed the Brotherhood's work, stated, “Good pictures never can be illustrations; they are always another poem subordinate but wholly different from the poet’s conception and serve chiefly to show the reader how variously the same verses may affect various minds."@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 231-256. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. |

|

Hunt’s portrayal of the Lady as being fallen and sexually charged is perhaps the greatest divergence in Hunt’s painting from Tennyson’s poem. While Tennyson’s Lady remains “passive, docile, and selfless"@Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 34. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>., Hunt’s Lady is presented as a fallen Victorian woman, who “threatens to subvert her prescriptive selflessness"@Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): 34. Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.. She has become, in a sense, a monster woman who can no longer redeem her lost purity. Hunt conveys this concept through various elements of artistic detail. While Hunt’s original 1850 sketch depicts the Lady with a small - almost frail - frame, she has grown into a “creature” of significant size@Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>. - that would break through the image's frame if she were to lift her head - in his 1857 Moxon version.

|

As mentioned earlier, the Lady’s hair has also transformed from being

neatly tied at the back of her neck to loose hair that seems to be

flying around, out of control@Thomas L. Jeffers. "TENNYSON'S LADY OF SHALOTT AND PRE-RAPHAELITE RENDERINGS: STATEMENT AND COUNTER-STATEMENT." Religion & the Arts 6.3 (2002): 235. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 2 Feb. 2011.. The Pre-raphaelite painters were

exceedingly fond of women’s hair – especially long flowing hair – which

is interpreted as a symbol of female sensuality@Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>.. The Victorian viewer

saw unruly hair to be closely associated with uncontrolled sexuality.@Shuli Barzilai, "Say That I had a Lovely Face": The Gimms' "Rapunzel," Tennyson's "Lady of Shalott," and Atwood's Lady Oracle." Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature 19.2 (2000): 242.

In Hunt’s painting, her hair becomes “a metaphor for monstrous female sexual energies.”@Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>. Her thick and tangled mass of hair is often said to be derived from the mythical creature, Medusa. Her hair appears to be alive and “vibrate with libidinous energy… like a vigorous brood of snakes".@ But it is not merely the Lady’s hair that resembles the mythical monster, but her very character. Both characters transform from a pure “beautiful” woman to one who is fallen and cursed through the attainment of a sexual conscience. While Medusa’s story is explicit with the sexual element that causes her fall, its connection with the Shalottian figure causes viewers to conceptualize a sexual element of immorality in Tennyson’s Lady. In a sense, Hunt has perverted and violated the ideological innocence of Tennyson’s Lady within the viewer’s mind. Tennyson’s verbal disapproval of Hunt’s portrayal of the Lady’s hair can be seen as a clear expression of disapproval regarding Hunt’s overall representation of the Lady as a fallen woman.

In Hunt’s painting, her hair becomes “a metaphor for monstrous female sexual energies.”@Sharyn R. Udall. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s “Lady of Shalott”.” Woman’s Art Journal 11.1 (1990): Woman’s Art Inc. Web. 2 Feb. 2011. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358385>. Her thick and tangled mass of hair is often said to be derived from the mythical creature, Medusa. Her hair appears to be alive and “vibrate with libidinous energy… like a vigorous brood of snakes".@ But it is not merely the Lady’s hair that resembles the mythical monster, but her very character. Both characters transform from a pure “beautiful” woman to one who is fallen and cursed through the attainment of a sexual conscience. While Medusa’s story is explicit with the sexual element that causes her fall, its connection with the Shalottian figure causes viewers to conceptualize a sexual element of immorality in Tennyson’s Lady. In a sense, Hunt has perverted and violated the ideological innocence of Tennyson’s Lady within the viewer’s mind. Tennyson’s verbal disapproval of Hunt’s portrayal of the Lady’s hair can be seen as a clear expression of disapproval regarding Hunt’s overall representation of the Lady as a fallen woman.