We're Mad About Lady Audley's Secret

pbayless, agrabin and rebekahtaussig

We're Mad About Lady Audley's Secret: Constructions and Consequences of Madness In and Around Mary Elizabeth Braddon's Novel, by Peter Bayless, Angela Rabin, and Rebekah Taussig

Lady Audley’s Secret and Sensation Fiction: The Dangers of Sensation Fiction

–Michel Foucault

|

Victorian readers in mid-century searching for a masterfully crafted and

tantalizing work of sensation fiction had to look no further than Mary

Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, for this novel

contained bigamy, scandalous crimes, and even madness, just to name a

few of her “secrets.” According to Victorian critics, sensation fiction

“heightened sensory images and passions that could corrupt the morals of

its readers” (Braddon, Introduction, 19). Indeed, in a scathing, yet

hypocritical, critique, Margaret Oliphant labels Braddon as the

“inventor of the fair-haired demon of modern fiction,” in reference to

the novel’s reigning vixen, Lady Audley. (263). Oliphant dubbed Braddon

the “leader of her school,” attributing such title to her fame and

numerous loyal “disciples” (265).

According to June Sturrock, Victorian society’s existing interest in sensational crimes ascended to new heights with the infamous 1860 murder case involving sixteen-year-old Constance Kent, who was arrested for the murder of her three-year-old half brother (73). Although the charges against her were later dismissed, she confessed to the crime in 1865, and was sentenced to death. However, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment (73). As Sturrock notes, the interest in this notorious case stemmed not so much from the violence of the act (the child’s throat was cut), or age of the murder victim. Rather, the Victorians were captivated by “the accusation of a violent family crime against a young and middle-class woman” (73). High-profile crimes such the Kent murder contributed to Victorian culture’s anxieties regarding gender, privacy, and transgressions in the early 1860s, and served as the inspiration for Braddon’s “quintessential sensation novel,” Lady Audley’s Secret (73). |

Madness and the Sensation Novel

The novel’s wayward heroine, Lucy Audley, confesses that she is “mad” in an effort to explain her crimes and why she assumed a new identity before marrying Michael Audley. In conceding victory to her accuser, Robert Audley, Lady Audley exclaims, “You have conquered—a madwoman!” (354). When Robert confronts her about the presumed murder of George Talboys, Lady Audley replies, “I killed him because I AM MAD! because my intellect is a little way upon the wrong side of that narrow boundary-line between sanity and insanity” (355). Although Lady Audley admits that her lucidity lingers on the “wrong side” of the sanity/insanity question, she also attributes her madness to her own mother. However, is Lady Audley indeed “mad” by virtue of her genetic inheritance, as she claims, or is she merely responding to the boundaries, restraints, and required standards of behavior Victorian society imposed on her and, by extension, to all women of that period?

Background: Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1835-1915)

|

As a novelist, editor, actress, daughter,

lover, and mother, Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s life shared the sensational flavor

found in her stories. From a career on

the stage, to living and having children with a married man, to penning what

some considered scandalous novels, Braddon did not live inside the lines of

conventional Victorian expectations.

Throughout

her career, Braddon produced massive amounts of work. She usually composed several stories at the

same time, averaging one to three novels a year for most of her career. A large portion of Braddon’s work was

considered “penny fiction.” These sensational

stories indulged in themes of crime, bigamy, murder, and madness, and found an

avid audience in the working classes.

Braddon received harsh censure from many critics for the composition of

such stories. W. Fraser Rae complains

that Braddon’s stories contaminate pure minds with false notions of human

nature. He regards them as “mischievous

in their tendency, and as one of the abominations of the age.” Margaret Oliphant claims that Braddon has

tainted the craft of novel writing.

According to Oliphant, the English novel was supposed to “call the

highest development of art, as for a certain sanity, wholesomeness, and

cleanness,” but Braddon sullies the elevated purpose of fiction writing by composing

“nasty novels” that corrupt the fair minds of the “young women of good blood

and good training.” Oliphant does not

just critique Braddon’s books, but takes a jab at Braddon’s character,

suggesting that Braddon may be entirely too disconnected from the world of

proper young ladies to know what these young women want to read. |

Background: The Sixpenny Magazine

Ironically, during much of the initial run of Sixpenny during the year preceding this column, Lady Audley’s Secret had been serialized instead in Robin Goodfellow, one of the cheaper magazines to which the anonymous columnist refers and which was actually owned by the same individual, publisher John Maxwell ("Robin Goodfellow (1861)" and "Maxwell, John (1824-1895)"). When Robin Goodfellow closed shop after twelve issues, before Braddon’s novel could be completely serialized, Maxwell re-serialized it in the pages of his newer and slightly higher-class magazine, where, one may assume, it formed a welcome part of the new era in affordable yet quasi-respectable literature to which the columnist alludes.

Seeing Madness

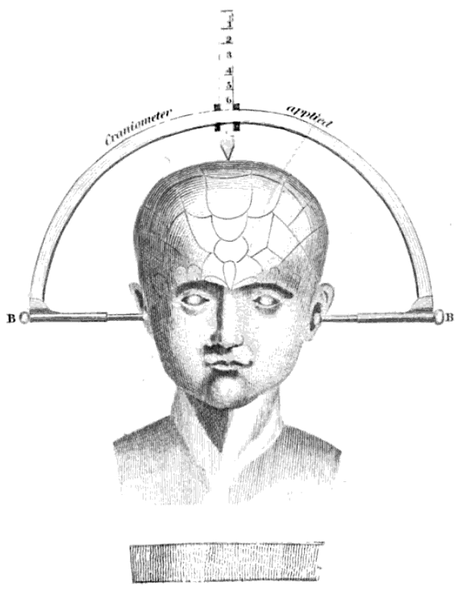

In addition to its more noticeable, purely intellectual and social approaches to the feminine, the criminal, and the insane, Lady Audley’s Secret significantly occupied and to some degree defied an ongoing discourse of its time concerning the physical and physiological manifestations of mental conditions. As late as 1870, several years after the novel’s first serialization, Henry Maudsley in the lectures that formed the basis of his Body and Mind was able to state in all earnestness that the operations of the mind were inextricably intertwined with the aesthetic and physiological manifestations of the self’s corporeal exterior. “We cannot truly understand mind functions,” he wrote, “without embracing in our inquiry all the bodily functions and, I might perhaps without exaggeration say, all the bodily features” (Maudsley 24, emphasis added). Therefore, when a patient is mad, “he [or, we may assume, she] is… lunatic to his fingers’ ends” (41). He approvingly cites another thinker who argues that the “criminal class”—a category having “close relations of nature and descent to… insanity”—was distinguished by low or degenerate physical characteristics (66). To describe this collection of governing principles, Lynn Voskuil coins the phrase “somatic fidelity,” the idea that “the body necessarily and indisputably betrays its inner truths” (613).

|

|

Such scrupulous and methodological

(if also spurious) measurements and mappings of the cranium did not, of course,

translate directly into preconceptions of the aesthetic and cosmetic

manifestations of madness, but the widespread credence that was lent them gave

room for hypotheses like Maudsley’s to take hold. And if Maudsley himself did not focus so much

on exactly what a lunatic woman might be expected to look like, Charles Darwin

(who not coincidentally credited Maudsley for inspiration and assistance in

obtaining models and notes (Darwin 20)) was prepared to fill the void. In his The

Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin reproduces a singular

image entitled, imaginatively, “From a photograph of an insane woman, to show

the condition of her hair.”

Lest one assume that the example given is simply that of a woman whose mania leads her to bizarrely style her own hair, Darwin takes pains to explain the correlation of the hair to the mental illness through purely involuntary physiological processes. In cases like this, he relates, the hair “’rises up from the forehead like the mane of a Shetland pony’” (296) and becomes drier and harsher, so that the wisdom earlier cited by Maudsley about being a lunatic to one’s fingers’ ends also applies “to the extremity of each particular hair” (298). The converse was also held to be true: “’I think,’” Darwin quotes a report, “’Mrs— will soon improve, for her hair is getting smooth, and I always notice that our patients get better whenever their hair ceases to be rough and unmanageable’” (298).

Perhaps, then, the growing reliance on scientific language and methodology to lend credibility to such beliefs may have magnified the potential for fear where such convictions were shaken and subverted. It was such subversion that one Henry Bellair used to shock and titillate his readers in a magazine article entitled “The Lunatic Beauty,” in which he wrote of the “thrilling curiosity and profound awe” evoked when “the countenance of the demented wears the lineaments of beauty and intelligence,” as opposed to the more honest “face[s…] the conformation of which indicates lunacy” (118). Bellair’s solution, to keep Voskuil’s somatic fidelity intact, is to make his anecdote of Adele Collaston a case of what might be called artificial insanity—the natural beauty received her mental illness unnaturally, via a blow on the head (and, in not the most medically or socially progressive resolution ever, is accidentally cured via another application of such violence). Lady Audley’s Secret transgresses further by not allowing its audience this measure of safety. In fact, Braddon’s novel goes so far as to directly put a point on the fact that Helen Talboys’s ostensible nascent or latent madness is hereditarily obtained from her mother, a woman who, like Helen herself, is “no raving, strait-waistcoated maniac […] but a golden-haired, blue-eyed, girlish creature” with “yellow curls” and “radiant smiles” (358). Therefore, Lady Audley (née Talboys) transgresses and sensationalizes not most because she is potentially mad but because she would be mad under false pretenses, mad in defiance of her exterior. As Voskuil writes, she “variably thrill[s] or disgust[s]” Victorian audiences because she looks the part of Victorian womanhood and wifehood but refuses to be it (613), but the reverse is equally true and salient: she professes the part of the madwoman, but refuses to look it.

Badness as Madness

At the same time, some found humor in bringing

madness into the courts. An 1862 issue

of Punch published the article “The Jonathan Lunacy Case,” which

satirized the trial of an “alleged lunatic.”

While his charges are not made explicit, the witnesses called to the

stand generally represent Jonathan as a “silly,” obnoxious drunk who merely requires

some discipline in his life. Madness is

a hot topic for the Victorians, but there is still much confusion on how it

should be defined and what role it can play in the court system and society as

a whole.

This distinction between a lack of morals and

madness was of particular importance to the Victorians, especially as it

related to criminal behavior and incarceration.

This tension is acted out in Lady Audley’s Secret when Dr.

Mosgrave visits Audley Court. The big

question posed to the doctor becomes one of how to account for Lady Audley’s

bad behavior – in other words, is she “bad” because she is mad? Interestingly enough, the doctor initially

says no. He finds Lady Audley’s behavior

perfectly accountable, reasoning:

Not only is Lady Audley considered entirely sane,

but she is spoken of as brave, ingenuitive, and strong – all qualities given

much more credit in a female of the twenty-first century than one of the

mid-nineteenth century. After having a

private (and mysterious) meeting with Lady Audley, the doctor complicates his

previous response. Now he proclaims that

Lady Audley, “has the cunning of madness, with the prudence of intelligence…She

is dangerous!” (Braddon 385). This shift

highlights a particular tension in the Victorian identification of madness; it

exposes a connection between diagnosis and a felt threat to the established

norms. Lady Audley’s independence,

determination, and strength were dangerous in a female. A diagnosis of madness reins her in to

something explicable and, quite literally, containable. In this way, the medical discourse supports

and reaffirms society’s expectations.

Women are to be submissive, docile, and dependent. Those who are otherwise are mad.

As Victorians consider how to define madness,

Braddon calls her audience to analyze the motivation behind the behavior often

deemed “mad” and re-examine the confines that force women into impossible

situations. “Braddon suggests to the

reader that Lucy is not deranged, but desperate; not mad (insane) but mad

(angry)” (Matus 344). The rigid and

sometimes contradictory expectations of the Victorian female pen Lady Audley

into a corner, and she lashes out in a way similar to what Braddon describes as

a wild animal caught in a trap. Instead

of seeing her “bad” behavior as evidence of insanity, Braddon seems to suggest

that society should adjust its morality gate.

Victorian Madhouses: Treatment Facilities or Convenient Incarceration?

From Assimilation to Incarceration

The Asylum

|

In

“The Lunatic Asylum,” William Ainsworth (1855) describes the aesthetics of an asylum

located in a rural England county: a “red brick building, very ugly in its

style of architecture, as nearly as large as Buckingham Palace” (91). The asylum is not a warm, inviting place,

having been built for “strength” instead of “ornament,” protected on the

outside by “upright iron bars” on the windows, and securely enclosing its

residents with big-brother-like “staring wings” (91). Aside from the humorous comparison to the

Royal residence, the imposing structure seems to be at odds with the

surrounding landscape, which Ainsworth (perhaps tongue-in-cheek) describes as

“luxuriant, well-kept acres of pleasure-grounds” (91). |

Criminal Asylum

|

When George Sala and Edmund Yates served as editors of Temple Bar, they pledged to use their editorial authority to keep the politics out of their publication, but “sensational fiction, short stories, and essays became a staple” (Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism). Whether intended or not, however, their article, “Criminal Lunatics,” which appeared in the December 1860 issue of Temple Bar, makes a social and political statement about criminal asylums and their resident inmates while adding a touch of sensation. In each of the five criminal case summaries they reference, the defendant was found not guilty by reason of lunacy. These defendants were spared the gallows for their felonious crimes, but little did they know what “doom” lay ahead for them in the insane asylum (136). Dispensing with any language that would suggest peace and serenity in the happy valley of the asylum, Sala and Yates instead informed their readers that the acquitted would be |

|

The Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum opened in 1863 as the first attempt to place the criminally insane in a separate facility where they could receive treatment unique to their mental conditions. Proposed in 1860 under the provisions of an Act that passed the same year, the Broadmoor Asylum was the result of repeated requests by the Metropolitan Commissioners between 1850 and 1860 (Parry-Jones, The Trade in Lunacy, 67). Referencing the then forthcoming state lunatic asylum, Sala and Yates anticipated that the new institution would remedy the “evils of the present system…by a better classification system of the patients, and by providing better opportunities for their occupation and amusement” (Sala and Yates 137). Despite the Commissioners’ noble ambitions and careful planning to meet estimated demands, overcrowding became a problem too soon, and Broadmoor (as well as other county and borough asylums) could not “fulfill their early promise” (Parry-Jones, “Asylum” 408). Today, the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum is known as Broadmoor Hospital, a reflection of society’s negative perception of the word “asylum.” The preferred euphemism of “hospital” is rather interesting given the “before” and “after” images of the Broadmoor Asylum/Hospital. Although the original asylum did have the appearance of an institution rather than a warm, inviting home, it has evolved into what appears more foreboding, complete with the confining perimeter chain linked fence.

|

Works Cited

Bellair, Henry. "The Lunatic Beauty." Reynolds miscellany of romance, general literature, science, and art 35.896 (1865): 118-9.

British Periodicals. Web. 24 April 2012.

Braddon, Mary Elizabeth. Lady Audley’s Secret. Ed. Natalie M. Houston. Orchard Park, NY: Broadview Press, 2003. Print.

“Broadmoor Asylum.” <http://www.francisfrith.com/broadmoor,berkshire/memories/cricketing-memories-at-broadmoor_239/> Web. 10 April

2012.

“Broadmoor Hospital.” <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Broadmoor_Hospital_-_geograph.org.uk_-_106921.jpg> Wikimedia Commons.

Web. 17 April 2012.

“Constance Kent.” <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ConstanceKent.jpg> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2012.

Cooley, Thomas. The Ivory Leg in the Ebony Cabinet: Madness, Race, and Gender in Victorian America. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P,

2001. Print.

“Curiosities of Madness.” Trewman's Exeter Flying Post or Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser. 11 April, 1860. Print.

Darwin, Charles (1809-1882). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Oxford, New York: Oxford UP, 1998. Print.

“Engraving of craniometer from ‘Elements of phrenology’ (1835).” <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Craniometer.Elements.of.phrenology.George.Combe.1.png> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2012.

"FIG. 19.—From a photograph of an insane woman, to show the condition of her hair." <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Expression_of_the_Emotions_Figure_19.png> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2012.

Frith, William Powell. Mary Elizabeth Maxwell (née Braddon). National Portrait Gallery, London. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mary_Elizabeth_Maxwell_(née_Braddon)_by_William_Powell_Frith.jpg> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 22 April 2012.

Houston, Natalie M. Introduction. Lady Audley’s Secret. By Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Ontario: Broadview Literary Texts, 2003. 9-29.

Print.

"Literature of the Month." The Sixpenny Magazine 1.4 (1861): 490-502. British Periodicals. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

“Madness and Guilt.” The Hampshire Advertiser. 9 August 1862: 8. Print.

Matus, Jill L. “Disclosure as ‘Cover-Up’: The Discourse of Madness in Lady Audley’s Secret.” University of Toronto Quarterly 62.3

(1993): 334-355. Print.

Maudsley, Henry (1835-1918). Body and Mind: An Inquiry Into Their Connection and Mutual Influence, Specifically in Reference to Mental

Disorders. London: Macmillan and Co., 1870. Print.

“MAXWELL, JOHN (1824-1895).” C19: The Nineteenth Century Index: Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism. Web. 24. Apr. 2012.

Nemesvari, Richard. “‘Judge by a Purely Literary Standard’: Sensation Fiction, Horizons of Expectation, and the Generic Construction of

Victorian Realism.” Victorian Sensations: Essays on a Scandalous Genre. Eds. Kimberly Harrison and Richard Fantina. Columbus: Ohio

State University Press, 2006. 15-28.

Oliphant, Margaret. “Novels.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. Sept. 1867: 257-280. Print.

Parry-Jones, William L. “Asylum for the Mentally Ill in Historical Perspective.” Bulletin of the Royal College of Psychiatrists 12.10

(1988): 407-410. Print.

--. The Trade in Lunacy: A Study of Private Madhouses in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. London: Routledge & Kegan

Paul, 1972. Print.

“Phrenology-journal clean.” <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phrenology-journal_clean.jpg> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April

2012.

Rae, W. Fraser. “Sensation Novels: Miss Braddon.” The North British Review. Sept. 1865: 180-204. Print.

“ROBIN GOODFELLOW (1861).” C19: The Nineteenth Century Index: Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism. Web. 24. Apr. 2012.

Sala, George A. H. and Edmund H. Yates. “Criminal Lunatics.” Temple Bar Dec. 1860: 135-143. Print.

Scull, Andrew R. Museums of Madness: The Social Organization of Insanity in Nineteenth-Century England. London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1979. Print.

Showalter, Elaine. “Victorian Women and Insanity.” Madhouses, Mad-Doctors, and Madmen: The Social History of Psychiatry in the

Victorian Era. Ed. Andrew Scull. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981. 313-336. Print.

Sturrock, June. “Murder, Gender, and Popular Fiction by Women in the 1860s: Braddon, Oliphant, Yonge.” Victorian Crime, Madness, and

Sensation. Eds. Andrew Maunder and Grace Moore. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004. 73-88. Print.

“St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics.” <http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f4/St_Lukes_Hospital_for_Lunatics%2C_London.jpg>

Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2012.

“The Causes of Madness.” Dundee Courier and Daily Argus. 2 July 1861. Print.

“The Jonathan Lunacy Case.” Punch 42 (11 January 1862): 11. Print.

Wolff, Robert L. “Devoted Disciple: The Letters of Mary Elizabeth Braddon to Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, 1862-1873.” Harvard Library

Bulletin 22 (1974): 129-161. Print.

Voskuil, Lynn M. "Acts of Madness: Lady Audley and the Meanings of Victorian Femininity." Feminist Studies 72.3 (2001): 611–639.