An Introduction to D.G. Rossetti

Jerome J. McGann

University of Virginia

The Works

The point of departure for reading Rossetti has to be Walter Pater's essay on the poetry, which he published in 1883 shortly after Rossetti's death. The strongest as well as the subtlest literary-critical intelligence of the period in England, Pater saw "poetic originality" as the defining quality of Rossetti's work. The writing features an "almost grotesque materialising of abstractions" and stylistic "particularisation". Pater's essay explores the paradox of a writer seen as both limpid and abstruse. On one hand Rossetti covets a "transparency in language" devoted to "the imaginative creation of things that are ideal from their very birth". On the other he is "always personal and even recondite, in a certain sense learned and casuistical, sometimes complex or obscure".

|

Like Pope, when Rossetti came into his own as a writer he was quite young, in his teens; and although some of the work from his later years is arguably stronger or more profound, the prose and poetry composed between his fifteenth and twentieth years is already mature, in full possession of his distinctive poetic resources. Coleridge, Keats, Tennyson, Poe, and Browning: these are the English-language writers who stand behind his work and lead him to that "originality" Pater recognized. Almost equally important, of course, were the writers Rossetti himself named "Dante and His Circle." Indeed, Dante is probably Rossetti's single most important precursor, partly because he supplied Rossetti with his central myth of the poet's life, and partly because, in seeking to reconstruct that myth through his translations, Rossetti was led to fashion an English style that has been materially marked by Italian linguistic and poetical resources. |

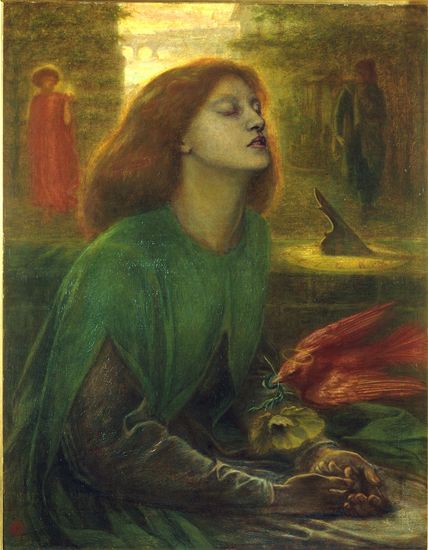

The combination of Rossetti's favorite English poets and his Italian verse inheritance lies behind that astonishing signature work of Rossetti's late teens, "The Blessed Damozel," with its paradoxical combinations - rhythmical as well as figurative.

|

Beatrice is gone up into high Heaven, |

The first two passages, which open the second and third stanzas of Rossetti's translation of Dante's famous canzone "Gli occhi, dolenti," fashion remarkable English equivalents for Dante's hendecasyllabic rhythms. The third passage is his translation of the opening of Cavalcanti's sonnet "Chi e questa, che ven" and it nicely exhibits a number of stylistic features that Rossetti will incorporate into his English verse. Notable are the synaesthesia, the sharp rendering of abstractions, the resort to sequences of brief words that subtly highlight key longer words ("coming", "tremulous", "himself", "infinite"), the careful rhythmic arrangement of the latter, and, finally, the slightly off-rhymes. The rhyming resources of Italian will draw Rossetti to develop many unusual rhymes and rhyming rhythms, some of them shocking, even outrageous. |

|

It lies in Heaven, across the flood |

This is more than a process of materializing spiritual realities and abstract ideas. Rossetti is rather literalizing that range of perceived and unperceived phenomena, turning it into a new kind of reality, purely linguistic. The effect inevitably recalls Coleridge's commentary on "Kubla Khan" as a vision in which "all the images rose up before [him] as things." Here we would be inclined to say "all the images and all the rhythms".