A Deconstruction of Victorian Gender Identity through the Lady of Shalott

Meaghan Munholland & Matthew Wright

Ryerson University

1300

The Lady of Shalott

John William Waterhouse

|

The medieval revival in the Victorian era was not a glorification of Britain’s mythical past, but rather a veneration of its present. Victorian society contemporized the chivalrous ideals of "knights" and "damsels," projecting self-reverence through popular medieval characters and settings. @Debra N. Mancoff, The Return of King Artur: The Legend through Victorian Eyes (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1995): 8.

The depiction of Victorian society within an appropriation of Arthurian values is particularly prominent in regards to the construction of gender. Alfred Tennyson’s 1832 (revised in 1842) poem " The Lady of Shalott" first appeared in Poems, which was the second volume of the writer’s poetry to be published under his full name. @Anna Jane Barton, "'What profits me my name?' The Aesthetic Potential of the Commodified Name in Lancelot and Elaine." Victorian Poetry 44.2 (2006): 140. Tennyson’s poem epitomizes the projection of the specific gender roles assigned to men and women of the Victorian era through the medieval lens. As with many poetic works, there have been numerous visual materials associated with Tennyson’s poem. One of the most iconic paintings connected to Tennyson’s text is John William Waterhouse’s 1888 oil on canvas painting titled The Lady of Shalott. This exhibit demonstrates how distinct gender roles illustrated in both Tennyson and Waterhouse's works, respectively, mimic the socially constructed characteristics of the sexes throughout the Victorian era. Although Tennyson and Waterhouse's works were created more than half a century apart, both poet and painter construct similar representations of the masculine and the feminine, illustrating the stagnation of gender roles throughout a century credited with great change and progress. This exhibit explores how, and to what extent, both the poem and painting reflect specific traits that were derived from a Victorian projection of gender identities. |

Alfred Tennyson's "The Lady of Shalott" expresses the struggle of a young, forlorn woman who longs so desperately for the affection of a romanticized, ideal male companion that this longing ultimately leads to her death. This exhibits an overarching theme in many of Tennyson's poems: "the tension between the artist’s desire for aesthetic withdrawal and the recognition of the need for responsible commitment to society."

@Jon C. Stott, Raymond E. Jones, and Rick Bowers. The Harbrace Anthology of Literature 2nd ed. (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Canada, 1997): 179. She becomes so enslaved by her desire for Lancelot that she loses all social value, thereby sacrificing her role as a "good" and obedient female. The idea of sacrifice is also evident in Waterhouse’s painting as the artist includes candles in his depiction of the Lady of Shalott. Burning candles are often elements in a sacrificial ceremony and in this sense Waterhouse uses the three candles, two of which are extinguished, to illustrate the self sacrifice of the Lady’s status and ultimately her forfeiture of life. She abandons her daily obligations and instead resorts to live in a far-off idea of chivalrous fulfillment in order to transcend her current condition. She desires an Arthurian knight in shining armour, who will act as her enabler and who will inject meaning into her otherwise fragmented and incomplete existence. In this portrayal of gender, femininity is endowed with fragility and powerlessness, while masculinity is embodied with strength and decisive action. The female character, in this regard, becomes the slave whose emancipation can only be enabled by the male (the master).

In Tennyson's poem the ideal of the protagonist remains unfulfilled. There is no plot-turn toward emotional relief; she is never saved or empowered by the man she longs for. Instead, her only act of pseudo-empowerment is the arguably unconscious provocation of the curse she is under, which ultimately leads to her death. The poem, then, ends with the irony of Lancelot watching her lifeless body float past him down a stream as he muses over her beauty. What makes this event even more ironic and tragic is how her death immediately follows a life of negation. At no point does she experience relief or fulfillment, "the Lady simply exchanges one kind of imprisonment for another; her presumed freedom is her death." @Shuli Barzilai, "Say That I Had a Lovely Face": The Grimms' "Rapunzel," Tennyson's "Lady of Shalott," and Atwood's Lady Oracle." Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature 19.2 (2000): 232. As a Tragedy of Errors, the poem alludes to a fundamental misunderstanding causing conflict and irresolution. The idea of female subservience stems from a patriarchal interpretation of femininity and both Tennyson and Waterhouse construct their "Ladies" to be pleasing to them as men and as masters/creators. |

John William Waterhouse

Photograph by Mendelssohn, c.1886.

|

The fact that the Lady is not named plays a significant role in establishing her identity, or lack thereof. Names signify identity to the external world and are internalized by the bearer.

@Barton 135. In Tennyson’s poem, the title character is known as 'The Lady of Shalott' and her given name is never revealed. She is named after the physical space in which she is imprisoned. She is identified by her circumstance of captivity rather than as an individual. The negation of the Lady’s name illustrates that her position as a woman in need of a male rescuer is valued above her own identity. The Lady also illustrates the power of naming and its internalizing effect as she identifies herself as 'The Lady of Shalott,' inscribing the moniker on the side of her boat.

A Deconstruction of Victorian Gender Identity through the Lady of Shalott

Meaghan Munholland & Matthew Wright

Ryerson University

1301

Although the Lady remains nameless, the male object of her affection is identified by name. Lancelot epitomizes the idea of chivalry and can easily be compared to the ideal Victorian gentleman as outlined in John Henry Cardinal Newman’s 1852 text

The Idea of a University.

@John Henry Cardinal Newman, The Idea of a University (New York: Image Books, 1959): 217-219.

Lancelot appreciates beauty as he remarks upon the Lady’s attractiveness and he is brave as the only onlooker of the Lady’s corpse who ponders rather than exhibiting fear. Lancelot also "acknowledges the being of God,"

@Newman 219.

as he asks the Divine to "lend her grace."

@Alfred Tennyson,"The Lady of Shalott," ENG 633: 19th Century Literature and Culture II Course Reader, ed. Lorraine Janzen (Toronto: Ryerson University, 2011) 162. Although in many respects Lancelot does exhibit the traits of a Victorian gentleman, he fails to fulfill Newman’s chief requirement of a gentleman who "is mainly occupied in merely removing the obstacles which hinder the free and unembarrassed action of those about him."

@Newman 217.

Lancelot is not concerned with the Lady’s circumstances and is wholly ignorant of her and her despair, although she is certainly "about him" as he travels "beside remote Shalott."

@Tennyson 161.

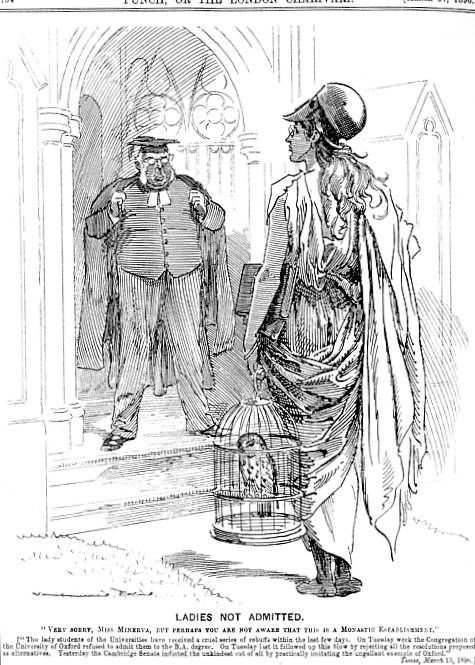

"Ladies Not Admitted"

Punch Magazine, March 1896

|

Newman’s The Idea of a University offers a perceptive commentary regarding higher education, yet women are completely absent from the text. The negation of women from The Idea of a University illustrates that higher education is a gentleman’s domain thus maintaining women’s ignorance and intellectual stagnation. The Victorian male desire to withhold knowledge from women is epitomized in Tennyson’s poem as the Lady is ignorant of what exists beyond the fragmented reproduction of reality through shadows. When the Lady is enlightened regarding the outside world, her knowledge, and acknowledgment, of the external leads to her death. The cartoon titled " Ladies not Admitted," which appeared in the Victorian humour magazine Punch on March 21st 1896, shows a male educator denying the Roman goddess of wisdom, Minerva, entrance to a University. This satirical illustration demonstrates the broader Victorian social belief that a woman’s place was not within the walls of an intellectual space but rather femininity is more congruent within the walls of a domestic space @Mancoff 72.

such as the Lady of Shalott’s enclosure where she tends to her domestic duty of weaving. In Victorian culture, women were considered ideal solely based on their moral and domestic achievements and their ability to provide comfort and pleasure to men. @Mancoff 74. |

While Newman’s The Idea of a University is void of female consideration, Waterhouse’s painting physically depicts only femininity. The Lady of Shalott is alone which illustrates vulnerability. She is also clutching to a chain that connects her to the shore. The chain is symbolic of her imprisonment in the tower and the fact that Waterhouse paints the Lady still holding the chain insinuates a reluctance to completely rid herself of her former controlled existence. Although Waterhouse’s painting shows only the Lady, Lancelot is still present in the visual image. Although not physically represented, an impression is established in the viewer that he is existent in the Lady’s mind. Waterhouse depicts the Lady in her trance-like state, yet her pained expression insinuates that she is yearning for her knight of Camelot. The Victorian male viewer would have received great pleasure from being able to penetrate the Lady’s thoughts and to find a revered member of his own sex preoccupying the mind of the fragile female.

The Lady of Shalott is idealized by the male reader because she is subservient. She is content with her weaving and does not question her role as an entrapped female with no agency or power. She is controlled and compelled by an abstract containment (the curse) as Victorian females are under the control of the abstract concept of the male dominated society of the nineteenth century. However, when the Lady of Shalott subverts the situation in which she has been compelled to comply with, she dies. This reflects the idea of dying a "social death" for Victorian women who balked patriarchal norms. After witnessing the shadows of two young lovers, the Lady is no longer compliant with her isolation and entrapment and longs to see the world as it is and not through shadowy reproductions. The fact that she becomes disillusioned after she sees a sexual act between a man and a woman, illustrates that she herself is a sexual being and yearns for a male partner. This breaks with the male construction of an idealized female who is sexually ignorant and repressed and the remainder of the poem demonstrates the consequences for a sexually self aware woman. She is a "fallen" woman, no longer figuratively and literally elevated in her tower, who is cast down physically and socially in the eyes of the male reader.

A Deconstruction of Victorian Gender Identity through the Lady of Shalott

Meaghan Munholland & Matthew Wright

Ryerson University

1338

I am Half-Sick of Shadows - said the Lady of Shalott (1915)

John William Waterhouse

|

Waterhouse also explores the idea of a fallen woman in his painting. He paints the Lady of Shalott in white, staying true to Tennyson’s text, which is symbolic of her former innocence and angelic status. The Lady’s hair, however, juxtaposes the "goodness" of her white dress. Waterhouse paints the Lady with her hair down, in its untamed natural state. Other Waterhouse paintings, which depict the Lady in her tower, are shown with the Lady’s hair up, styled and tidy. This signifies that while she is imprisoned she is moral and refined, yet when she exposes herself to the external world to which she was denied, she is unruly and uncontrolled. To Victorian viewers, untamed hair was a marker of uncontrolled sexuality @Barzilai 242. which again illustrates the Lady of Shalott as being constructed as a sexual being commencing at the end of Part 2 of Tennyson's text. |

The depiction of the Lady of Shalott in both Tennyson's poem and Waterhouse's painting are derived from a patriarchal idealization of an idealization. That is, the Lady herself idealizes precisely what a patriarchal male would want her to idealize, in order to fulfill his own idea of the perfect female. This plays into a perverse pleasure that the stereotypical Victorian male reader would have derived from the protagonist’s suffering. John William Waterhouse was at the tail end of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, which was a response to the more posed, formulaic styles of the Renaissance-inspired Mannerists, like Raphael and Caravaggio. Pre-Raphaelites are known for taking inspiration from Romanticism and Medievalism, which they believed enabled the strongest emotional response from their viewers. This is part of what makes Waterhouse's The Lady of the Shalott so appealing to the Victorian man; like a modern Hollywood film, the characters are designed to be extra-ordinary, the product of fantasy rather than reality. This is precisely the intention of both Waterhouse and Tennyson, to mythologize a female character who is the visible personification of absolute perfection, and then to add the heart-wrenching twist of impending tragedy. Waterhouse painted The Lady of Shalott with idealized proportions, using colours accentuated to 'pop', in order to establish the impression of an uncanny, dream-like state.

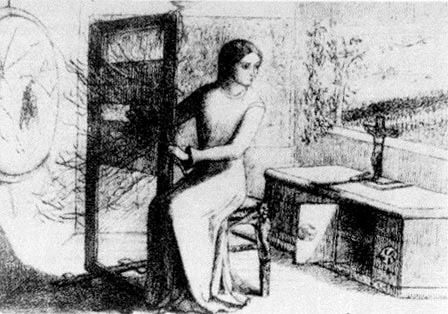

In contrast to Waterhouse’s lavish oil on canvas painting, Elizabeth Siddal’s 1853 pen and ink on paper illustration titled The Lady of Shalott at Her Loom explores the female perception of the title character. Siddel uses unadorned techniques to represent the Lady of Shalott which mirrors the Lady’s gray and bland existence in her tower. It is also interesting to note that Siddal’s visual work was created thirty five years prior to Waterhouse’s painting. This demonstrates the evolution of the visual interpretation Tennyson’s poem through a gendered, but also historical lens. The simplicity of Siddal’s medium demonstrates that a female artist does not see the Lady as an idealized and extra-ordinary fantasy but rather as a lonely woman who longs for something beyond her current situation. Siddal also perceives the Lady as a moral figure as the artist’s illustration prominently displays a crucifix, which is not present in Tennyson’s poem. Arguably, many Victorian females would have empathized with the Lady of Siddal's visual work as an imprisoned and isolated woman. They would have championed her attempt to free herself from her repressive constraints and pitied her when she fought and lost the battle over her own destiny. |

The Lady of Shalott at Her Loom

Elizabeth Siddal

|

Pictures at Play: The Lady of Shalott & The Dicksee

Illustration by Harry Furniss

|

Between Tennyson’s poetry and Waterhouse’s painting is an interesting inter-textual communication that is alluded to in a series of satirical sketches that were published in the same year the painting was first unveiled to the public.

Pictures at Play, or Dialogues of the Galleries,

@Andrew Lang, William Ernest Henley and Harry Furniss, Pictures at Play, or Dialogues of the Galleries (New York: AMS Press, 1970) Print. written by art critics Andrew Lang and W.E. Henley, and illustrated by Harry Furniss, brings Waterhouse’s

The Lady of Shalott to life as a speaking character who interacts with other paintings in an art gallery and sings reflectively about her own conception and depiction as a piece of art. In

Act V of the play, she mentions a connection between her and Victorian realist painter Jules Bastien-Lepage,

@Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V. whom Waterhouse took stylistic inspiration from, painting the Lady with similar blocks of colour and thick brush strokes characteristic of Lepage's style. The Lady communicates with another female character in a Sir Frank Dicksee painting, whom the Lady calls "Little Dicksee," envying her for having been depicted in an "age of innocence."

@Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V. This character of purity incarnate tells the Lady of Shalott that she is deceived; she expresses that there is a secret sadness in herself as well. Similarly, the Lady points out that she has been dismissed by some critics as simply the work of "an excessively rising young Associate"

@Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V. instead of as the victim of unrequited love, posing shortly before her death. This further explains the necessity of a context within the painting; without an understanding of Tennyson's poem, Waterhouse's Lady becomes an entirely different character. It is the viewer of the painting who enables it, through his/her own subjectivity. In this way, inter-textuality plays an essential role in establishing the Lady's character in Waterhouse's work. The more these paintings and poems communicate with each other, the greater their meaning and aesthetic response becomes.The satirical verses of

Pictures at Play demonstrate the self-awareness of the Lady as an icon of female objectification. She recognizes that she has been doomed both by Tennyson and Waterhouse, to be immortalized in a state of glorified despair. This is because the painting is a response to the aesthetic ideals prescribed by the poem. Therefore, it is the background knowledge of the viewer that enables them to derive that the Lady is the product of patriarchal social values which expect women to be subservient and everlastingly faithful to their male counterpart, even when he is unattainable. And in

Pictures at Play, it is this implied understanding that personifies the Lady into a talking character.

Although Tennyson and Waterhouse's works were created over half a century apart, the objective of both poem and painting was to express a fundamental disconnect between the facts of reality and the transcendence of idealization. The Lady herself seems to stem from the perverse male idealization of an entirely faithful female admirer, who literally submits herself as his romantic slave. Despite the artistic and literary advancement throughout the Victorian era, it is clear through the examination of both Tennyson and Waterhouse's works that the portrayal of femininity remained relativity static. Both text and painting depict womanhood as something to be idealized, but also something to be punished if an attempt is made to subvert male dominated, societal norms. The initial emotional response of serenity and idyllic beauty is fundamentally deceptive. In order to fully appreciate the Lady of the Shalott, the viewer/reader has to experience disappointment at some level, to realize the Lady's sadness peaking through the otherwise perfect scene. This creates an interesting parallel between viewer/reader and subject matter - just as the Lady experiences the misery of an intrinsic lack of fulfillment, so must the textual and visual audience, who must accept the imperfection of the scene. This is part of what makes the Lady of the Shalott so endearing - that above all, the emotional effectiveness of her character relies on an aesthetic response of empathy between her and the audience.

A Deconstruction of Victorian Gender Identity through the Lady of Shalott

Meaghan Munholland & Matthew Wright

Ryerson University

Endnotes

1 Debra N. Mancoff, The Return of King Artur: The Legend through Victorian Eyes (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1995): 8.

2 Anna Jane Barton, "'What profits me my name?' The Aesthetic Potential of the Commodified Name in Lancelot and Elaine." Victorian Poetry 44.2 (2006): 140.

3 Jon C. Stott, Raymond E. Jones, and Rick Bowers. The Harbrace Anthology of Literature 2nd ed. (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Canada, 1997): 179.

4 Shuli Barzilai, "Say That I Had a Lovely Face": The Grimms' "Rapunzel," Tennyson's "Lady of Shalott," and Atwood's Lady Oracle." Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature 19.2 (2000): 232.

5 Barton 135.

6 John Henry Cardinal Newman, The Idea of a University (New York: Image Books, 1959): 217-219.

7 Newman 219.

8 Alfred Tennyson,"The Lady of Shalott," ENG 633: 19th Century Literature and Culture II Course Reader, ed. Lorraine Janzen (Toronto: Ryerson University, 2011) 162.

9 Newman 217.

10 Tennyson 161.

11 Mancoff 72.

12 Mancoff 74.

13 Barzilai 242.

14 Andrew Lang, William Ernest Henley and Harry Furniss, Pictures at Play, or Dialogues of the Galleries (New York: AMS Press, 1970) Print.

15 Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V.

16 Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V.

17 Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V.

Links

Page 1

"The Lady of Shalott" http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/tennyson/los1.html

"What profits me my name?' The Aesthetic Potential of the Commodified Name in Lancelot and Elaine" http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/journals/victorian_poetry/v044/44.2barton.html

"The Lady of Shalott" http://www.jwwaterhouse.com/view.cfm?recordid=28

""Say That I Had a Lovely Face": The Grimms' "Rapunzel," Tennyson's "Lady of Shalott," and Atwood's Lady Oracle."" http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/stable/464428?seq=1&Search=yes&searchText=Face&searchText=I&searchText=Lovely&list=hide&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3DSay%2BThat%2BI%2BHad%2Ba%2BLovely%2BFace%26acc%3Don%26wc%3Don&prevSearch=&item=13&ttl=21811&returnArticleService=showFullText&resultsServiceName=null

Page 2

"The Lady of Shalott" http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/tennyson/los1.html

"Ladies not Admitted" http://www.victorianweb.org/periodicals/punch/69.html

Page 3

"The Lady of Shalott at Her Loom" http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/siddal/drawings/3.html

"Act V" http://www.johnwilliamwaterhouse.com/articles/pictures-at-play-lady-of-shalott/