Michael Field's La Gioconda: Redefining Female Beauty In Art

Alix Caissie and Nicole Farrell

Ryerson University

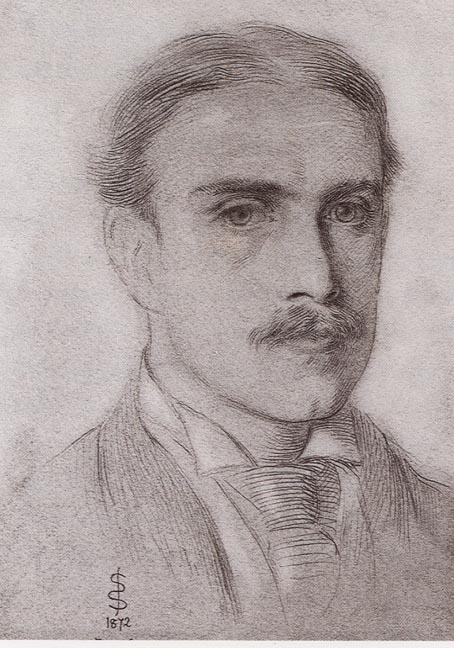

Edith Emma Cooper and Katherine Harris Bradley

@

<span title="External Link: http://thefindesiecle.com/post/540805414/unbosoming-by-michael-field-katherine-bradley" real_link="http://thefindesiecle.com/post/540805414/unbosoming-by-michael-field-katherine-bradley" class="ext_linklike">http://thefindesiecle.com/post/540805414/unbosoming-by-michael-field-katherine-bradley </span>

Michael Field

|

Art in the Victorian era was primarily focused on the importance of aesthetics and beauty for beauty’s sake. Women quickly became revered for their physical beauty and thus were the inspirations for many works of art. Since women were the source of inspiration, the majority of writers and artists were male, and viewed the female form as something to be admired through poetry and imagery. During this time, a poet named Michael Field became prominent in the literary circle for poems inspired by the female form. Although on the surface it appears that Michael Field was just another male writer, in actuality the name was a pseudonym for two females who were in a relationship together. Edith Emma Cooper and Katherine Harris Bradley chose to write under a male name because at this time, women were oppressed and not taken seriously in the art and literary sphere. In choosing to write under the pseudonym of a male alias, they were able to circumvent public gender criticism, and furthermore allow for the possibility to push beyond what was considered acceptable from female writers.@Lee, Michelle. "Inventing Michael Field: Can Two Women Write like One Man?" Poetry Foundation. 27 January 2010. March 16 2011. Through this, they were able to explore and reinvent perspectives on art which to some extent allowed for their work to be read without bias against their gender. |

|

Marion Thain describes Michael Field as “a created and creative space of lyric production,”3Thain, Marion, and Ana Parejo Vadillo. Ed.Michael Field, The Poet:Published and Manuscript Materials. Canada: Broadview Editions 2009. Print. which defines the duo not as two individuals working in tandem, but as a complete and separate entity which functions with the purpose of creating singular works of poetry and drama. Although conducive to their own relationship as lovers, this sense of uniformity was controversial within the Victorian context, as it devalued the importance placed on singular authority and individualism. 4Lee, Michelle. "Inventing Michael Field: Can Two Women Write like One Man?" Poetry Foundation. 27 January 2010. March 16 2011.This focus on singularity reflects the dominant male perspective and opinion on art which this essay will explore in further detail in reference to the painting La Gioconda by Leonardo Da Vinci. La Gioconda was painted in the early 1600s but became a part of popular culture in the 1800s due to the accessible reproduction of the image via the printing press. As one of the most famous images of a female, much has been written about her beauty. In exploring the various perspectives, it has become apparent that when viewed through the eyes of a male, La Gioconda becomes inherently sexualized and in turn victimized because the observer demonstrates power over the objectified female image. In the poem “La Gioconda” by Michael Field, there is a transfer of power in which the female image is interpreted as having dominance which contradicts the more traditional male view. This essay will analyze Walter Pater’s essay on La Gioconda and his interpretation of the female image as both an idealized and sexualized object in contrast to Field’s perspective on reconfiguring the sexualization of the male observer and transferring dominance from the male observer to the female image.

|

|

The physical female body was praised as being the ultimate in beauty, but the mental, emotional and intellectual aspects of women were thusly oppressed. The focus on bodily beauty overshadowed the women themselves and turned their physicality into a commodity. Many women in paintings were portrayed as being “a young girl crying silently, a suffering Madonna, asleeping prostitute...” which are “images of passivity and subservience.” @Byecroft, Breanna. "Representations of the Female Voice in Victorian Poetry." Brown University, 2003. Victorian Web. 17 December 2003. March 16th 2011.Although the focus was on the outward appearance of women, they were not painted in neutral or positive settings or situations. Instead, they were represented in positions of submissiveness and had little power or authority over their selves and bodies. The female image was desired and lusted after, and even idealized and made unrealistic, but was not respected. This meant that the power lied with the male observer who was not only oppressing women’s voices in literature and art, but also degrading their worth by manipulating their physical images. Since males were sexualizing the female form and expressing the importance of beauty, women were seen as objects of sexualized wanting and portrayed as passive, submissive, and weak. In an article exploring how women are portrayed in Victorian art, it is argued that male speakers impose their own voices and opinions upon women, thus silencing women from having their own ideas and also compressing their entire aura into one fixed meaning.@Byecroft, Breanna. "Representations of the Female Voice in Victorian Poetry." Brown University, 2003. Victorian Web. 17 December 2003. March 16th 2011. This objectivist approach towards women was the traditionalist perspective during this era, and Field set out to explore and redefine gender influence in aesthetics. The male perspective is incredibly narrow as its focus is purely on physical aesthetics, whereas Field’s goal was to create a more subjective view that would take into account the complexity of feelings and emotions behind the art form. |

Michael Field's La Gioconda: Redefining Female Beauty In Art

Alix Caissie and Nicole Farrell

Ryerson University

|

Pater’s essay on the painting La Gioconda focuses mainly on how he interprets Da Vinci’s inspiration and perspective. He argues that Da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa as a representation of his “ideal lady, embodied and beheld at last.”@Pater, Walter Horatio. "The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry." Leonardo

Da Vinci 98-129.Victorian Web. 9 October 2003. 1 February 2011. Again, the concept of objectification is brought into the interpretation of art. The woman being “beheld at last” creates the notion that she is something hard to attain and thus worshipped, making her essence less realistic and more idealistic. The suggestion of Da Vinci having created the Mona Lisa as the ideal of femininity is congruent to the dominant male observation of sexualizing women in art. He goes so far as to say that when “set...beside those white Greek goddesses or beautiful women of antiquity..how they would be troubled by this beauty!”@Pater, Walter Horatio. "The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry." Leonardo

Da Vinci 98-129.Victorian Web. 9 October 2003. 1 February 2011. Not only is the Mona Lisa the idealized woman, but she is even more beautiful and more yearned for than goddesses, who are known for being untouchable and the ultimate in male adoration. It is also important to note that Pater chose to analyze La Gioconda in an essay format, and focused on Da Vinci’s inspiration behind the painting. Instead of personally expressing his feelings about the painting through poetry or more informal prose, he structured an essay which reflects the rigidity and objectivity of the male observer. His focus on Da Vinci’s interpretation shows his attention to how other males saw the image and what might have inspired Da Vinci to paint La Gioconda, which he deduces as an idealization of the perfect woman. By choosing to write a structured essay, his argument becomes a representation of the objectivity of the male observer and the focus on one fixed meaning of the image rather than in Field’s poetry which was a more personal reflection and subjective in its exploration of what the female image represented. |

|

Field, however, denies this objectivity and instead presents La Gioconda as a figure who denies the male gaze and takes on a more dominant role outside male objectification. As Lyseck presents, the first half of “La Gioconda” plays into the exchange of the female form as an object of male consumption, listing off the desired attributes which demonstrate how easily the female image can be consumed.@Lysack, Krista. "Aesthetic Consumption and the Cultural Production of Michael Field’s Sight and Song."SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-190045.4 (2005): 935-960. 2 Feb 2011. The breaking down of the female form into the eyes, lips, cheek,

and smile mimics the approach that Pater takes, which defines the female “not as a real woman, but as a series of male fantasies.”@Ehnenn, Jill. “Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song.” Victorian Poetry. 43.1 (2005): 109-154. 2 Feb 2011. Furthermore, the implementation of the word “historic” to describe these qualities is a direct critique towards Pater’s idealization of La Gioconda, and the eternalization of the female as a sexualized commodity. Accordingly, Field’s utilization of this word allows them to enter into a criticism not only of Pater’s essay, but of the encompassing role of female aesthetic within the Victorian context; whereby they can move away from simply translating the painting to arguing for its importance in redefining the female aesthetic experience. |

A smile of velvet's lustre on the cheek;

Calm lips the smile leads upward; hand that lies

Glowing and soft, the patience in its rest

Of cruelty that waits and does not seek

For prey; a dusky forehead and a breast

Where twilight touches ripeness amorously:

Behind her, crystal rocks, a sea and skies

Of evanescent blue on cloud and creek;

Landscape that shines suppressive of its zest

For those vicissitudes by which men die.@Field, Michael. “La Gioconda.” Sight and Song. London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane, 1892. 87. Rpt in Michael Field, The Poet: Published and Manuscript Materials. Ed. Marion Thain and Ana Parejo Vadillo. Canada: Broadview Editions, 2009.

|

With the introduction of a semi-colon on the third line of the verse, “La Gioconda” suddenly takes on Field’s perspective.@Parejo Vadillo, Ana I. "Sight and Song: Transparent Translations and a Manifesto for the Observer."Victorian Poetry38.1 (2000): 15-34. Web. 2 Feb 2011. The poem switches, turning away from the description of the female form to a description of her motive. Yet, the introduction of the lines, “hand that lies/ Glowing and soft, the patients in its rest/Of cruelty that wait and doth not seek/For prey” presents a duality. On one hand, the act of passivity attributed to La Gioconda, “exposes the institutionalized silencing of women under the male gaze,”@Ehnenn, Jill. “Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song.” Victorian Poetry. 43.1 (2005): 109-154. 2 Feb 2011. thus providing a strict critique of Pater assertion of male dominance. However, it also demonstrates a resistance within the figure, which provides La Gioconda with agency. Although the passivity provides that La Gioconda does not become outwardly dominant, it does create a sense of imagery where she appears almost spider-like, waiting patiently for those seeking only her beauty to become entrapped in her web. La Gioconda then becomes the one that preys on the subject, turning the objectification towards the reader, whereby they become consumed by her. Moreover, with the introduction of the colon on the seventh line, Field is denying the consumption of the image as a whole. By directing the reader towards the background, they refocus the reading to something which is “far less satisfying,”@Lysack, Krista. "Aesthetic Consumption and the Cultural Production of Michael Field’s Sight and Song."SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-190045.4 (2005): 935-960. 2 Feb 2011 reinforcing La Gioconda’s dominance as woman outside of a sexualized object.

|

Michael Field's La Gioconda: Redefining Female Beauty In Art

Alix Caissie and Nicole Farrell

Ryerson University

Endnotes

1 <span title="External Link: http://thefindesiecle.com/post/540805414/unbosoming-by-michael-field-katherine-bradley" real_link="http://thefindesiecle.com/post/540805414/unbosoming-by-michael-field-katherine-bradley" class="ext_linklike">http://thefindesiecle.com/post/540805414/unbosoming-by-michael-field-katherine-bradley </span>

2 Lee, Michelle. "Inventing Michael Field: Can Two Women Write like One Man?" Poetry Foundation. 27 January 2010. March 16 2011.

3 Byecroft, Breanna. "Representations of the Female Voice in Victorian Poetry." Brown University, 2003. Victorian Web. 17 December 2003. March 16th 2011.

4 Byecroft, Breanna. "Representations of the Female Voice in Victorian Poetry." Brown University, 2003. Victorian Web. 17 December 2003. March 16th 2011.

5 Thain, Marion, and Ana Parejo Vadillo. Ed.Michael Field, The Poet: Published and Manuscript Materials (Canada: Broadview Editions 2009.

6 Ehnenn, Jill. “Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song.” Victorian Poetry. 43.1 (2005): 109-154. 2 Feb 2011.

7 Lysack, Krista. "Aesthetic Consumption and the Cultural Production of Michael Field’s Sight and Song."SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-190045.4 (2005): 935-960. 2 Feb 2011.

8 Lysack, Krista. "Aesthetic Consumption and the Cultural Production of Michael Field’s Sight and Song."SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-190045.4 (2005): 935-960. 2 Feb 2011.

9 Pater, Walter Horatio. "The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry." Leonardo Da Vinci 98-129.Victorian Web. 9 October 2003. 1 February 2011.

10 Pater, Walter Horatio. "The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry." Leonardo Da Vinci 98-129.Victorian Web. 9 October 2003. 1 February 2011.

11 Lysack, Krista. "Aesthetic Consumption and the Cultural Production of Michael Field’s Sight and Song."SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-190045.4 (2005): 935-960. 2 Feb 2011.

12 Ehnenn, Jill. “Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song.” Victorian Poetry. 43.1 (2005): 109-154. 2 Feb 2011.

13 Field, Michael. “La Gioconda.” Sight and Song. London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane, 1892. 87. Rpt in Michael Field, The Poet: Published and Manuscript Materials. Ed. Marion Thain and Ana Parejo Vadillo. Canada: Broadview Editions, 2009.

14 Parejo Vadillo, Ana I. "Sight and Song: Transparent Translations and a Manifesto for the Observer."Victorian Poetry38.1 (2000): 15-34. Web. 2 Feb 2011.

15 Ehnenn, Jill. “Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song.” Victorian Poetry. 43.1 (2005): 109-154. 2 Feb 2011.

16 Lysack, Krista. "Aesthetic Consumption and the Cultural Production of Michael Field’s Sight and Song."SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-190045.4 (2005): 935-960. 2 Feb 2011

Links

Page 1

"Inventing Michael Field: Can Two Women Write like One Man?" http://www.poetryfoundation.org/journal/article.html?id=238584

"Inventing Michael Field: Can Two Women Write like One Man" http://www.poetryfoundation.org/journal/article.html?id=238584

"Representations of the Female Voice in Victorian Poetry." http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/ebb/byecroft14.html

""Representations of the Female Voice in Victorian Poetry."" http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/ebb/byecroft14.html

"Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song" http://muse.jhu.edu/content/nines/journals/victorian_poetry/v042/42.3ehnenn.html [Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field's Sight and Song]

Page 2

"The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry." http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/pater/renaissance/6.html

"The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry." http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/pater/renaissance/6.html

"Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song." http://muse.jhu.edu/content/nines/journals/victorian_poetry/v042/42.3ehnenn.html [Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field's Sight and Song]