How "A Musical Instrument" Embodies Divinity and Morality

Leah Rifkin and Sarah Cooper

Ryerson University

|

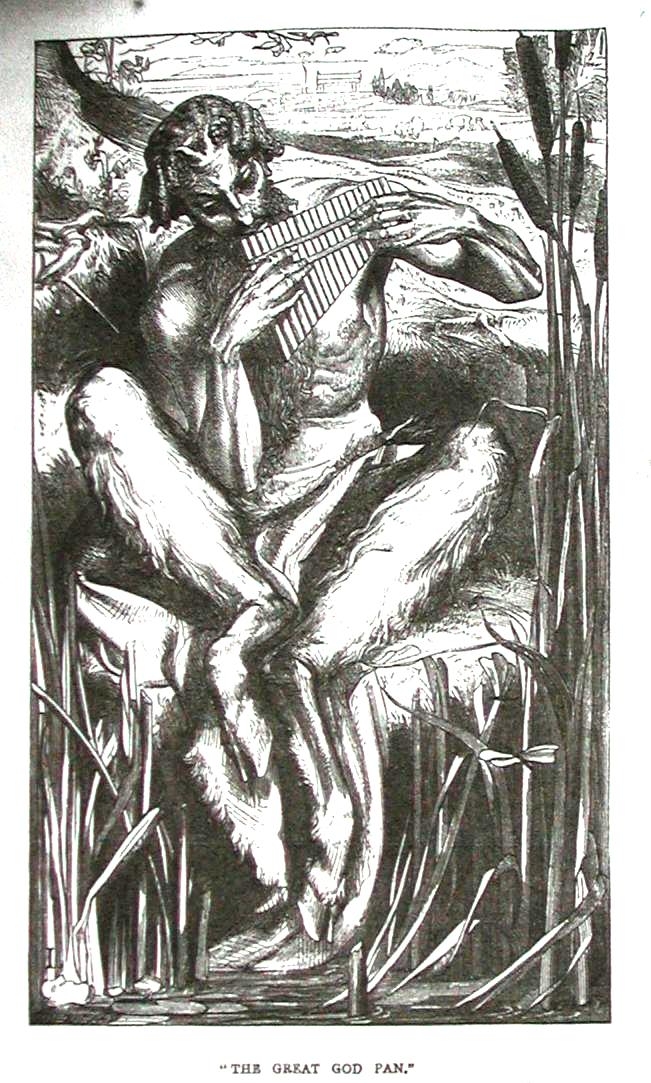

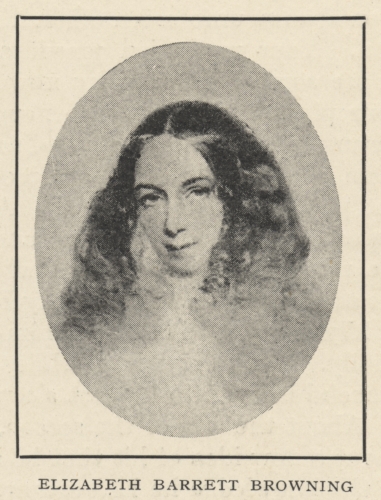

For our exhibit we have selected a Victorian poem written by Elizabeth Barrett Browning called "A Musical Instrument". Our associated visual object is the wood engraving of "The Great God Pan" done by Frederick Leighton. Both of these were published in The Cornhill Magazine@Browning, Elizabeth B. "A Musical Instrument." Ed. William Thackeray. The Cornhill Magazine July 1860. C19 Index. Web. in July 1860. Our associated visual object is a digital image of Browning's poem in The Musical World@Browning, Elizabeth B. "A Musical Instrument." A Musical World 21 July 1860: 459. C19 Index. Web. also published in July 1860. We are interested in poetry as a device used by women to express their opinions and feelings about women's rights in the 19th century. Our research question is what the correlation is between the written and visual portrayal of Pan in Browning’s poem and Leighton’s carving. Furthermore, how do they regard music as a divine art and poetry as a form of feminism. While I will analyze the relationship between Gods and the portrayal of music’s divinity in the poem and Leighton’s wood engraving, Sarah will examine the physical and moral traits of Pan as described in the poem and shown in the engraving as well as their connection to gender roles and women’s suffrage in the late 19th century. We will also look at how the interpretations of the texts are altered depending on the publication in which one reads the poem, the placement of the poem on the page, and the varying reading practices that different publications attested to. |

|

An article written in 1882 titled Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics presents Lord Leighton's views on music as a divine art. For Leighton, all forms of art depend on religious sense and moral sense.@"Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics." The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular 1 Jan. 1882, Vol. 23, No. 467 ed.: 15-17. Musical Times Publications Ltd. Web. Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one of many Christian poets to have Judaic scripture and tradition provide inspiration for her poetry.@Hughes, Linda K. "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies." Victorian Periodicals Review 40.2 (2007): 91-125. Project MUSE. Web. Her religious sense is evident in the style and tone of her poem as the rhythmic pattern and the gospel-style discourse are present throughout. The repetition of the word ‘sweet’ in the phrase that reads “Sweet, sweet, sweet, O Pan!” is indicative of the phrase ‘sweet lord’ that is commonly used in sermons. The general placement of commas in the third and fourth lines of the fifth stanza also pays homage to the pauses and stresses made by pastors in their sermons. Browning’s poem exemplifies Leighton’s belief of music as a divine art and made her art form, which is poetry in this case, exude a sort of religious or divine musical style. |

How "A Musical Instrument" Embodies Divinity and Morality

Leah Rifkin and Sarah Cooper

Ryerson University

|

Another interesting line to consider is Pan’s profession that his method is “The only way, since gods began/ To make sweet music, they could succeed.” There are two ways to view this with regards to feminist themes. Is Elizabeth Barrett Browning advocating an infiltration into a prejudiced society through arts and culture, via music, writing, painting, etc? Or, perhaps she refers to Pan’s violent actions as a course for more direct, disruptive means such as protestation/remonstration and confrontation. In some regards, it could be that she supports both methods. This aggressive method is necessary to destroy the current way of living and end oppression. The other, artistic approach is necessary to heal the world and show that change is indeed positive. The suffering that oppression brought can be built into a positive, creative endeavor. The article points out that art can be free from morals and religion (which the poem is not), however the moral disposition of artists will still influence their work. E.B. Browning had high moral standards as seen in her decision to publish in The Cornhill Magazine.@"Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics." Musical Times and Singing Class Circular Jan. 1882: 15-17. C19 Index. Web.

|

|

The Cornhill Magazine had a certain prominence and reputation in Victorian society which lent the same sort of legitimacy to “A Musical Instrument”. By publishing her poetry in this magazine, E.B. Browning was insuring that she would be reaching women and informing them about the sort of feminist ‘upheaval’ that had already begun. The Cornhill had solidified its role as a well-known “family literary magazine” by 1860. Traditionally, public perception indicated that it was improper for women to be readers. For example, the 1832 painting "Le Roman" by Octave Tasaert depicts a woman engaging in sloppy, leisurely reading in a dark, ominous room. She is "mindlessly absorbing dangerous lessons from novels."@Bergman-Carton, Janis.The Woman of Ideas in French Art, 1830-1848. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print. The Cornhill, however, did not subscribe to the idea of women being in a secondary role with regards to reading. Instead, they highlighted the positive effects of women’s reading practices and encouraged women to think of themselves as a part of a serious reading audience.@Jennifer Phegley,Educating the Proper Woman Reader: Victorian Family Literary Magazines and the Cultural Health of the Nation. (Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2004) 71. Google Books. Web. The Cornhill was the best choice for a pro-feminism piece, in fact, as it was supportive of women’s education in order to better the nation as a whole, reasoning that it was easing men’s burdens. At the same time, it kept out overtly controversial issues that might stir concern from more traditional men not wishing ‘their’ women to be exposed to such things.@Jennifer Phegley,Educating the Proper Woman Reader: Victorian Family Literary Magazines and the Cultural Health of the Nation. (Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2004) 71. Google Books. Web. Despite this unfortunate viewpoint, this allowed for more women to be reached by authors such as Browning and as such The Cornhill certainly seems to be a good fit for “A Musical Instrument”. |

|

Another good periodical in which to fit E.B.Browning’s poem was The Musical World. The periodical may have been titled in this way to pay tribute to art that possesses divine elements presented as music through the cadence of poetic works or within the themes and explicit subject matter of literary texts. As a periodical, it was solely dedicated to the topic of music and the use of the word ‘World’ in the title gives music its own sacred literary realm in which to reside. Comparing the poem’s publication in The Cornhill Magazine and in The Musical World, it is clear that the interpretations of the poem change when there is an image associated with it. Poems in general require at least two inches in a column but if a poem is placed in the center of a page with white space around it, the poem itself will stand out.@Hughes, Linda K. "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies." Victorian Periodicals Review 40.2 (2007): 91-125. Project MUSE. Web. “A Musical Instrument” is known as an example of illustrated poetry and in The Cornhill, it is signed and separated from serial fiction.@Hughes, Linda K. "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies." Victorian Periodicals Review 40.2 (2007): 91-125. Project MUSE. Web. His image was placed after the fifth stanza on a separate page and not coincidentally placed directly subsequent to the two lines in the fifth stanza which his image is portraying. Thackeray made this obvious design decision to make it easier for the reader to make connections between the poem and the wood engraving, thereby making the message of the poem much more clear. For the reader having an image to refer to after reading the poem or between verses of a poem makes it more of a visceral experience.

|

How "A Musical Instrument" Embodies Divinity and Morality

Leah Rifkin and Sarah Cooper

Ryerson University

The Great God Pan

Frederick Leighton

|

An article by Elizabeth Prettlejohn@Prettlejohn, Elizabeth. "Morality versus Aesthetics in Critical Interpretations of Frederic Leighton, 1855-75." The Burlington Magazine 138.1115 (1996): 79-86. JSTOR. Web. 24 Mar. 2011. details the motivations for Frederick Leighton’s art. It discusses the idea of rating art based on being “purely artistic” rather than riddled with moral messages. Critics say there is a lack of expression in Leighton's work that contradicted the structure of expression as the base for communicating a message to the viewer. However, the article argues that he intentionally did not follow this common model because he wanted to depict a character's "social status, their psychological or emotional states, or their moral natures". Most of Leighton's pieces illustrate women, and his wood engraving of Pan can also be considered a subject of the female sex in terms of what the god symbolizes in the poem. True, he has a destructive nature that is inherently masculine in terms of 19th century roles because he smashes, destroys, and kills. He hacks and hews with a “hard bleak steel” and puts holes in it as he whittles is reed. The last line of the fifth stanza describes him blowing in “power by the river” which is distinctively masculine imagery with no softness to be found. |

|

But in the sixth stanza, the perspective on his actions has been subverted. He becomes a feminine embodiment through the repeated emphasis on the sweetness of his music. He is creating, giving life, which is traditionally considered the role of woman. He revives the dying lilies and entices the dragonfly to return. The enticing, soft, sweet, life-giving woman is the epitome of feminine character. It is this picture which Leighton has chosen to illustrate. Much like the poem itself, Pan is a seemingly masculine figure with some feminine undertones. While the image is of a very masculine body with well-defined muscles, strong facial features and a bushy beard, the body language suggests otherwise. His posture denotes a certain softness; his legs poised in a loose position and hands softly focused on producing the regenerative music. It is not the devastation that Leighton chooses to focus on but rather the moment of revival.

|

|

Some critics say that Leighton believed that neither music nor painting are proper tools for teaching morals. Art may have "an awakening influence, an ethos of its own, a power of intensification, and a suggestiveness through association which aid those higher moods of contemplation that are as edifying in their way as direct moral teaching”.@"Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics." Musical Times and Singing Class Circular Jan. 1882: 15-17. C19 Index. Web. One can pay close attention to Leighton's wood engraving of "The Great God Pan" to establish if it was successful in portraying the moral teachings which E.B. Browning’s poem explores. The poem presents morals and lessons about the divine importance of music (as an art form) and poetry (as a literary form) to Victorian society. Both are a means to express one’s thoughts and emotions concerning the issues of the time.

Indeed, issues such as the feminist movement went hand in hand with the art and culture of the time. Reading and writing were empowering acts for the 19th century woman who had traditionally been kept to the side with matters regarding education. As a female author, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s work is viewed with a separate kind of scrutiny. Her works were certainly feminist, and reading into the gender roles embodied within "A Musical Instrument" one will find a reflection of the times. Distinctly masculine with a feminine touch, Pan shows what the women of the 19th century were capable of and what women’s suffrage could do for society. |

How "A Musical Instrument" Embodies Divinity and Morality

Leah Rifkin and Sarah Cooper

Ryerson University

Endnotes

1 Browning, Elizabeth B. "A Musical Instrument." Ed. William Thackeray. The Cornhill Magazine July 1860. C19 Index. Web.

2 Browning, Elizabeth B. "A Musical Instrument." A Musical World 21 July 1860: 459. C19 Index. Web.

3 "Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics." The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular 1 Jan. 1882, Vol. 23, No. 467 ed.: 15-17. Musical Times Publications Ltd. Web.

4 Hughes, Linda K. "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies." Victorian Periodicals Review 40.2 (2007): 91-125. Project MUSE. Web.

5 "Pan - Myth Encyclopedia - Mythology, Greek, God." Encyclopedia of Myths. Web.

6 "Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics." Musical Times and Singing Class Circular Jan. 1882: 15-17. C19 Index. Web.

7 Maunder, Andrew. ""Discourses of Distinction": The Reception of the "Cornhill Magazine", 1859-60." Victorian Periodicals Review 32.3 (1999): 239-58. JSTOR. Web.

8 Bergman-Carton, Janis.The Woman of Ideas in French Art, 1830-1848. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

9 Jennifer Phegley,Educating the Proper Woman Reader: Victorian Family Literary Magazines and the Cultural Health of the Nation. (Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2004) 71. Google Books. Web.

10 Jennifer Phegley,Educating the Proper Woman Reader: Victorian Family Literary Magazines and the Cultural Health of the Nation. (Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2004) 71. Google Books. Web.

11 Hughes, Linda K. "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies." Victorian Periodicals Review 40.2 (2007): 91-125. Project MUSE. Web.

12 Hughes, Linda K. "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies." Victorian Periodicals Review 40.2 (2007): 91-125. Project MUSE. Web.

13 Prettlejohn, Elizabeth. "Morality versus Aesthetics in Critical Interpretations of Frederic Leighton, 1855-75." The Burlington Magazine 138.1115 (1996): 79-86. JSTOR. Web. 24 Mar. 2011.

14 "Sir Frederick Leighton on Art and Ethics." Musical Times and Singing Class Circular Jan. 1882: 15-17. C19 Index. Web.

Links

Page 1

"Web" http://www.jstor.org/stable/3357633

"Web" http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/vpr/summary/v040/40.2hughes.html

"Web" http://www.mythencyclopedia.com/Ni-Pa/Pan.html

Page 2

"Web" http://www.jstor.org/stable/20083684

"Web" http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/vpr/summary/v040/40.2hughes.html

"Web" http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/vpr/summary/v040/40.2hughes.html

Page 3

"Web" http://www.jstor.org/stable/886732