Truth and Fiction: the Art and Poetry of the Crimean War

Miya

A work of art, in its entirety, can stretch beyond the original canvas. The unique brand of art and poetry that arose out of the Crimean War, for instance, was defined by shifting perspectives and an ongoing dialogue between mediums. Thanks to technological advancements, Great Britain was in the midst of a major cultural flux, abandoning Romantic depictions of battle in pursuit of its painful, ugly realities. Thus, this exhibit will decipher Lord Tennyson's poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,”@Tennyson, Alfred. "The Charge of the Light Brigade." The Examiner 29 Dec. 1854. through its relationship to two visual artifacts: Roger Fenton's photograph “The Valley of the Shadow of Death”@Fenton, Roger. Shadow of the Valley of Death. 1855. Photograph. Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Illustrated London News. Print. and Punch magazine's political cartoon “The Reason Why.”@Leech, John. "The Reason Why." Ed. Mark Lemon and Henry Mayhew. Punch 29 (1855): 83. University of Toronto Archives. Web. 5 Mar. 2011. <http://www.archive.org/details/punch28a29/emouoft>. Each assumes a unique vantage point on the same pivotal moment, the Crimean War's Battle of Balaclava. However, it is only through cross-comparison that one truly grasps how the social and political landscape of a nation has a direct influence on the development of its culture.

|

The Charge of the Light Brigade |

Alfred Tennyson

(1809-1892)

|

At first reading, Tennyson's poem could be interpreted as a rallying battle cry, a patriotic declaration of support for an empire that had come under sharp public criticism. Indeed, contemporaries of Tennyson, such as Gladstone and Goldwin Smith, derided the poet's “stodgy,” political views.@Bennett, James R. "Maud's Battle-Song." Victorian Poetry 18.1 (1980): 35-49. Print. The Charge of the Light Brigade, in particular, was criticized for its apparent “war-mongering” spirit.@Sypher, F. J. "Politics in the Poetry of Tennyson." Victorian Poetry 14.2 (1976): 101-12. Print However, a closer reading of the text reveals that it is not the British empire the poet glorifies, but "the spirit of the common soldier," an important distinction that reflects a larger trend towards realism.

During the Crimean War, the lowest positions in the British army were often occupied by poor, working-class men. Enlisting out of desperation, these soldiers were subject to meagre pay and appalling living conditions with little chance of advancement.

Lalumia, Matthew. "Realism and Anti-Aristocratic Sentiment in Victorian Depictions of the Crimean War." Victorian Studies 27.1 (1983): 25-52. Print.

became the favoured subject of paintings, while the depiction of “high-born” military commanders faded into obscurity. Tennyson echoes this trend by placing the experience of the anonymous soldier at the forefront. By contrast, the commander of the troops is left unnamed, referenced only in a single line: “Some one had blundered.” Still, the poem has more than a touch

of romance. As literary critic F.J. Sypher points out, the idea of

glory in death, despite its futility, is a common theme throughout

Tennyson's work.@ Sypher, F. J. "Politics in the

Poetry of Tennyson." Victorian Poetry 14.2 (1976):

101-12. Print Sypher, F. J. "Politics in the

Poetry of Tennyson." Victorian Poetry 14.2 (1976):

101-12. Print

The Valley of the Shadow of Death

Roger Fenton, The Examiner

|

With the birth of photography, capturing reality, in its purest form, seemed possible as never before. Along with the telegraph, the invention of photography enabled the masses to access information at rapid-fire speed. No longer encumbered by the lengthy lag times of traditional post, journalists could relay battle events to the British public, almost as they unfolded. Against this backdrop emerged “the first iconic war photograph.”@Morris, Errol. "Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?" The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr., 25 Sept. 2007. Web. 5 Mar. 2011. <http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/25/which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg-part-one/>. When Roger Fenton's “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” was published in The Illustrated London News, it caused an instant sensation. Devoid of carnage or casualties, rather it is the suggestion of death that lends the image its power. The deserted enclave, muddied ground thick with canon ball shot and the faded footprints of doomed guardsmen, echoes with the ravages of war and “desolation of the human soul.”@Morris, Errol. "Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?" The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr., 25 Sept. 2007. Web. 5 Mar. 2011. <http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/25/which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg-part-one/>. |

|

However, the cameraman still presents an "edited reality," choosing who and what captures his photographic eye, while that which falls outside the frame is rendered obsolete.@In her book, Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag claimed several icon war photographs were, in fact, staged. In particular, she alleged that Fenton himself had placed the canon balls on the road to create a scene with greater emotional impact. In 2007, documentary filmmaker Errol Morris travelled to the original scene of the photo to investigate the merit of the argument, which he ultimately declared was unfounded. However, the "truth" of Fenton's famous photograph is still debated today. |

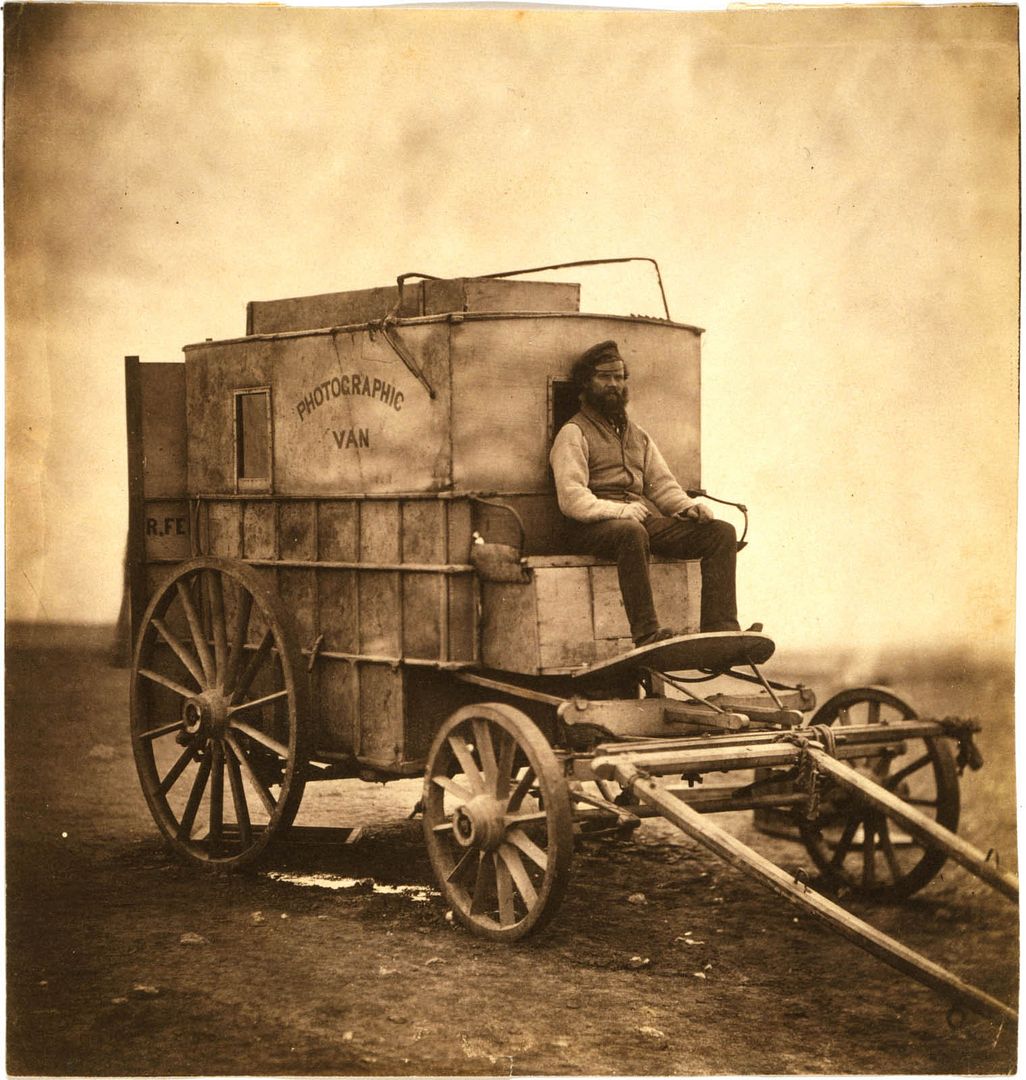

Roger Fenton's assistant Marcus Sparling

Seated in Fenton's mobile photography van, before entering "The Valley of The Shadow of Death"

|

It is important to note that artists and poets like Tennyson were included in the popular readership. For instance, British newspapers initially reported that 607 cavalrymen rode in the Battle of Balaclava, rather than the actual number of 700. Even after Tennyson learned of the error in latter reports, he opted to keep the original line because “six is much better than seven hundred... metrically.”@Yang, Cecil Y., and Edgar F. Shannon Jr., eds. Letters of Alfred Lord Tennyson. Vol. 2. New York: Harvard UP, 1987. Print. While the poet's decision to publish false information opens up a larger debate over the merits of aesthetics versus accuracy, it also raises another important question; one regarding the idea of a stable reality in an ever-changing world. With the rise of multimedia technology, Victorian society became increasingly information-driven, interconnected and, in some ways, transient. As a result, separating truth from fiction became more problematic. Tennyson speaks to the growing influence of the periodic press in his poem: “All the world wondered.” In addition, the following lines, “Into the valley of Death/Rode the six hundred,” are a direct reference to the title of Fenton's photograph, as it appeared in the Examiner. The title of the photograph, in turn, was likely inspired by the following psalm from the Old Testament: “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death/ I will fear no evil, for you are with me...” (Psalm 23:4). Thus, one becomes aware of an ongoing cross-chatter between mediums. Holding up a mirror to another mirror evokes the same effect; rather than a single image, the reflection contains an infinite volleying chasm, a copy of a copy of a copy.

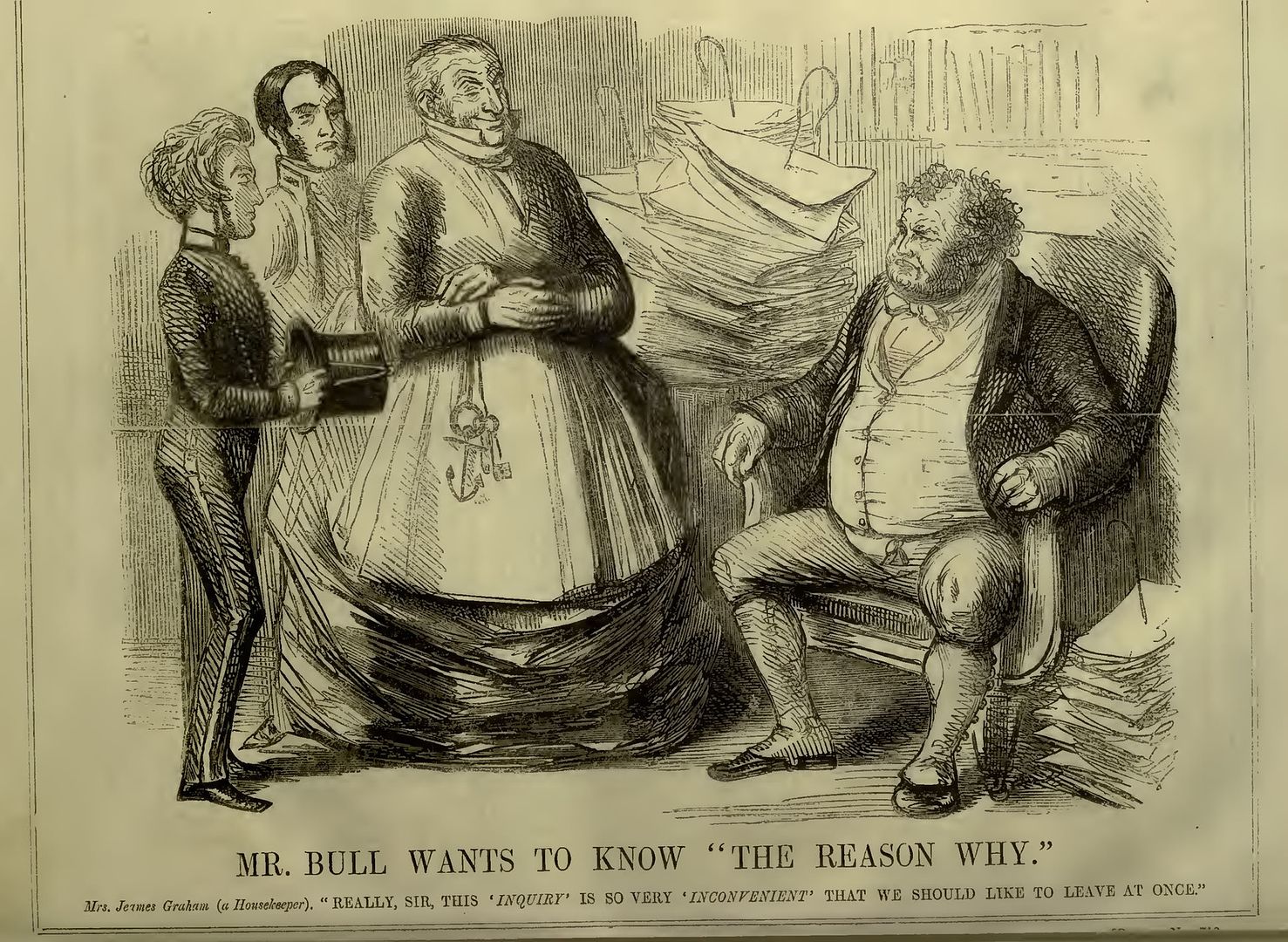

John Leech, "The Reason Why"

Punch magazine (1855)

|

For further evidence of this

inter-relationship, one turns to Punch magazine. The satirical comic, "The Reason Why," by

artist John Leech is a prime example of how Tennyson's poetry both

shapes and was shaped by the popular media. In Leech's political

cartoon, an aristocratic officer dressed as a housekeeper shoos away

the “mess” left behind by the disaster at Balaclava. Meanwhile, a

government official gazes on with furrowed brow, looking very much

like a stern headmaster chiding a naughty schoolboy. The

poetic reference, “There's not to reason why,/ There's but to do

and die,” is a testament to The Charge of the Light Brigade's

iconic status. However, the magazine's cheeky take on Tennyson also

shows how one can re-appropriate and reshape popular art, including

poetry, to give it new meaning. Leech implies that glory in death

alone is not a sufficient explanation. The people of Great Britain

demanded answers and for those responsible to be held accountable.@ As a direct result of public outcry

over the mishandling of the Crimean War, the British government ended

the purchase system in 1871, opting instead for a merit system “open

to all.” The “Cardwell reforms” included: shorter service

terms, more promotions, higher wages and better overall living

conditions for the soldiers. |

|

As a whole, the magazine quite

literally “re-frames” Tennyson's poetry within the context of the

times. This particular issue of Punch, for instance, also contains

the following scathing editorial, criticizing the military fiasco at

Balaclava: “That an old dowager, with money and influence, ought to

be able to buy her hobledehoys into the most respectable positions in

the British army... the argument was worthy of hearers who did not

instantly laugh it down.” There are other insights into the public

mood. An announcement that Queen Victoria would be visiting wounded

soldiers at Windsor, for instance, appears on a corresponding page.@ Although aristocratic officers were

heavily criticized for the mismanagement of the Crimean War, the

Queen herself became a symbol of new-found empathy for the plight of

wounded soldiers. In fact, according to Lalumia, Queen Victoria

herself commissioned a series of photographs of patients at a

military hospital in Brompton. The moving images, captured by

journalists Joseph Cundall and Robert Howlett, appeared in The

Illustrated London News in 1855.

|

Punch magazine cover (Jan. 1855)

|

In conclusion, the relationship between this triad of artists – poet, photographer and cartoonist – shows how a single historic event can be dissected through the prism of subjective experience. Only by comparing all three does one fully grasp the High Victorian era's underlying themes of chaos and disillusion. In this way, not only Tennyson's poem, but larger ideas of truth and fiction are exposed as complex, multivariate and, most importantly, ever-evolving.

Truth and Fiction: the Art and Poetry of the Crimean War

Miya

Truth and Fiction: the Art and Poetry of the Crimean War

Miya

Endnotes

1 Tennyson, Alfred. "The Charge of the Light Brigade." The Examiner 29 Dec. 1854.

2 Fenton, Roger. Shadow of the Valley of Death. 1855. Photograph. Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Illustrated London News. Print.

3 Leech, John. "The Reason Why." Ed. Mark Lemon and Henry Mayhew. Punch 29 (1855): 83. University of Toronto Archives. Web. 5 Mar. 2011. <http://www.archive.org/details/punch28a29/emouoft>.

4 Bennett, James R. "Maud's Battle-Song." Victorian Poetry 18.1 (1980): 35-49. Print.

5 Sypher, F. J. "Politics in the Poetry of Tennyson." Victorian Poetry 14.2 (1976): 101-12. Print

6 Lalumia, Matthew. "Realism and Anti-Aristocratic Sentiment in Victorian Depictions of the Crimean War." Victorian Studies 27.1 (1983): 25-52. Print.

7 During the Crimean War, the lowest

positions in the British army were often occupied by poor,

working-class men. Enlisting out of desperation, these soldiers were

subject to meagre pay and appalling living conditions with little

chance of advancement. Lalumia, Matthew. "Realism and Anti-Aristocratic Sentiment in Victorian Depictions of the Crimean War." Victorian Studies 27.1 (1983): 25-52. Print.

8 Sypher, F. J. "Politics in the

Poetry of Tennyson." Victorian Poetry 14.2 (1976):

101-12. Print

9 Sypher, F. J. "Politics in the

Poetry of Tennyson." Victorian Poetry 14.2 (1976):

101-12. Print

10 Morris, Errol. "Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?" The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr., 25 Sept. 2007. Web. 5 Mar. 2011. <http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/25/which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg-part-one/>.

11 Morris, Errol. "Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?" The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr., 25 Sept. 2007. Web. 5 Mar. 2011. <http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/25/which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg-part-one/>.

12 In her book, Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag claimed several icon war photographs were, in fact, staged. In particular, she alleged that Fenton himself had placed the canon balls on the road to create a scene with greater emotional impact. In 2007, documentary filmmaker Errol Morris travelled to the original scene of the photo to investigate the merit of the argument, which he ultimately declared was unfounded. However, the "truth" of Fenton's famous photograph is still debated today.

Morris, Errol. "Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?" The New York Times.

Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr., 25 Sept. 2007. Web. 5 Mar. 2011.

<http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/25/which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg-part-one/>.

13 Yang, Cecil Y., and Edgar F. Shannon Jr., eds. Letters of Alfred Lord Tennyson. Vol. 2. New York: Harvard UP, 1987. Print.

14 As a direct result of public outcry

over the mishandling of the Crimean War, the British government ended

the purchase system in 1871, opting instead for a merit system “open

to all.” The “Cardwell reforms” included: shorter service

terms, more promotions, higher wages and better overall living

conditions for the soldiers.

15 Although aristocratic officers were

heavily criticized for the mismanagement of the Crimean War, the

Queen herself became a symbol of new-found empathy for the plight of

wounded soldiers. In fact, according to Lalumia, Queen Victoria

herself commissioned a series of photographs of patients at a

military hospital in Brompton. The moving images, captured by

journalists Joseph Cundall and Robert Howlett, appeared in The

Illustrated London News in 1855.

Links

No links