[Peter Bayless] Evolution, Degeneration, Imagination: The Specter of Moral, Social and Physical Mutability in The Leisure Hour

pbayless

1937

Context: The Degeneration Imagination

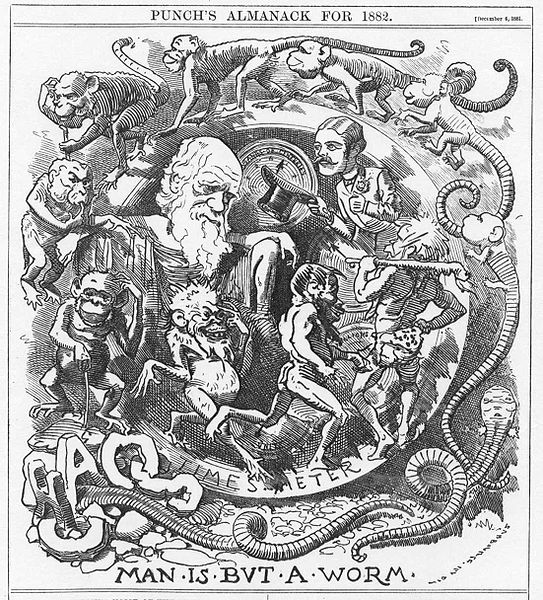

The abstract fears that came to be associated with scientific descriptions of degeneration have a long pedigree, of course--humans have been afraid of disease and death, and have been ascribing those same calamities (and many others) to divine agencies or to just retribution for immorality, for seemingly almost as long as written history has existed. It was during the nineteenth century, however, that the ‘rational’ or ‘physical’ sciences began to provide a compelling framework over which to drape these long-established moral fears. Charles Darwin's already-mentioned theory of natural selection, and similar ideas, stoked the fear of devolution even as they described its opposite: in order for natural selection to 'select,' for one group or entity to be 'chosen,' the thinking went, something else must be selected against--must be found unfit and thus die. Other, even more fundamental scientific descriptions of degeneration were being proposed in the form of the concepts of entropy and thermodynamics. As Chamberlain and Gilman write in the introduction to their anthology Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress, degeneration seemed like an indisputable, universal fact-- “people, nations, perhaps the universe itself” all grow old, die, and decay to dust (x). At the same time, the growing interest in scientific rationalism (or at least those portions of its discoveries that could be distilled for popular consumption) did not mean that superstition or supernatural dread disappeared overnight, as indeed they have not as we approach two centuries later. The Victorian generation was then one that had an increasing amount of apparently empirical verification for the religious idea that the visible world is not the ultimate reality, that the microscopic structure of the cosmos and (what we now call) the genetic could undermine the best-laid efforts of human beings. Small wonder, then, the popularity of the idea as reflected in pieces of news interest, cartoons, and other parts of the Victorian milieu. If there was one thing that both the theologically and scientifically minded of the day seemed to share, it was a preoccupation with narrative accounts of decline and fall. Degeneration, it seemed, offered something for everybody.

What was degeneration, precisely? Chamberlain and Gilman describe:

First of all, it meant to lose the properties of the genus, to decline to a lower type... to dust, perhaps, or to the behavior of the beasts of the barnyard. It also meant to lose the generative force, the force that through the green fuse drives the flower. (ix)

|

Fear of degeneration, then, encompassed a wide array of human phobias and aversions, any one of which, one imagines, could potentially trigger the association: fear of death, fear of becoming physically or cognitively disabled, fear of no longer being able to procreate or to see to one’s progeny as one would like. It was opposed to a “sanctity of types, or genuses, or species,” the social and moral implications of which will be seen when one realizes that this includes a comfort in the sense of belonging to one’s own racial, cultural or class group, and, as the authors mention, this belonging-to-category would become all the more frantically embraced the more uncertain it became (x). The more these fears grew, the larger a set of things took on a new meaning even if they might not have previously been associated, either implicitly or explicitly, with degeneration: fear of poverty, of different ethnic groups, of religious immorality. The scientific descriptions of evolution and its converses provided a “mode of coherence and continuity for the descriptions of phenomena” (xii). In other words, as Geoffrey Reiter puts it: degeneration was, firstly, terrifying because so many disparate fears could be subsumed under a single "aegis," and, conversely, was rhetorically useful because it was an indictment that could be applied to so many different things to "justify and articulate" the hostility towards them (218, 217).

|

|

As has already been alluded to, the use of degeneration as moral judgment had antecedents dating to long before a scientific language was developed to give it a greater (if spurious) sort of legitimacy. Eric Carlson notes that the core Christian doctrine of the Fall of Man, in the book of Genesis, is itself a story of medical affliction: to punish Adam and Eve for their sin of disobedience, God introduces a “bodily disposition towards illness and death and condemns future generations to this dismal bodily end” (Carlson 124). Likewise, Carlson observes that biblical stories of the taint of sin transmitting itself down through generations seemed to easily explain the observation that some chronic illnesses run in families. A preexisting association between morality and bodily health, or lacks thereof, thus already existed, and this association fitted neatly with the concept of degeneration as used by popular thought of the mid-19th century. It therefore comes as no surprise that the word carried moral weight and was used to condemn groups. In the case of other races--colonized populations, for example--evidence of degeneracy could be found in behavior and physiognomy alike. Native populations were seen as “morally underdeveloped” and this, in a pseudo-Darwinian misappropriation of the concept of environmental influence, was ascribed in part to the climate in which they made their homes; European colonists or soldiers, it was thought, could succumb to the same sort of “‘surexcitation of sexual organs’” arising from the tropic heat, and, combined with the bad influence of the natives themselves, could quickly become overstimulated, overindulged, and indolent.

|

|

Given the belief that ill moral, mental and social health themselves could be passed down to successive generations along with what were taken to be the physical markers of these maladies, among the many fears of degeneration was that of European societies themselves subsiding back into barbarism. If nature could cause an animal species to slowly lose viability and gradually be relegated to near extinction, so the thinking went, human races and kingdoms might likewise find themselves degenerating and being supplanted by others (102). The result was, at least at first, a perceived need to educate and police the society and individual in order to guide both to progress and away from decline. If virtues could be inculcated in the population, went this logic, the natural tendency towards degeneration could perhaps be averted (Nye 50-51). I believe that it is to this tradition that The Leisure Hour belongs, however subtly. The mission of the magazine and the Society, to socially and morally uplift were years or decades old in 1860, but the more recent idea of evolution had provided a useful framing rhetoric and a means of appealing to the reader with references to the exciting new science of the day. It is worth noting that at this early stage the specter of degeneration appears somewhat nascent and more subtle: like the ghosts in Dickens's A Christmas Carol, it is alluded to in order to warn, with the implication that disaster may be averted--that evolution rather than devolution may take place, whether racial, moral or societal. Later in the century, the idea of genetic degeneration would become much more entrenched in the popular understanding of history and the perception of the city as a place for opportunity and upward mobility would turn into one of a “breeding ground” for the subhuman “residuum” (64-65), but The Ferrol Family belongs, chronologically and in spirit, to a philosophy that hoped to uplift the working and middle classes.

|

The Leisure Hour did not necessarily batter its readers over the head with its moral messages outside of its fiction, at least not during the run of The Ferrol Family (the serial novel itself is arguably another matter). Nor did it explicitly connect, during this period, the pseudoscientific idea of degeneration with the moral decay it stood as a bulwark against. But instead, perhaps, it followed the same strategy in scientific education as it did in morals: subtly 'uplifting' readers with articles designed to appeal to their intellectual curiosity about the scientific developments of the day, carefully selected and presented so as to convey a sense of superiority and progress over previous epochs of history (and their supposed contemporary analogues). We would expect to find articles on popular science and society alike praise moral progress or warn against downfalls on a societal or biological level, or that encourage readers to take an interest in the sort of science that underlay these attitudes. A quick look at the magazine’s other content during the novel’s run supports this hypothesis. Two separate pieces entitled “Man among the Mammoths”-- one an article in its own right, another, later one a blurb in the Varieties column--appealed to an apparently current interest in biological and anthropological history, using tales of finds in the soil strata of England to invite readers to take pride in their own geographical origins, while disagreeing on whether exactly mankind actually lived among the mammoths. “Multiplication of Species,” also in the Varieties column, namedropped the then new and exciting Charles Darwin and his book, showing that such were supposed to be recognizable and of interest to the common reader. “A Night with the Ethnologists” featured the correspondent attending a scientific talk and reporting on the recently unearthed exotic skulls he had been privileged to witness firsthand, skulls for which the term “crania” was used as metonym and the precise cranial features of which were hypothesized to be directly correlated with their prior owners’ level of civilization. Finally, “Past versus Present” and “Fruits of the Revival in Ulster” both presented rosily optimistic views of the human capacity for evolution; “Past”’s author flatly rejecting the notion that the human race is degenerating and indeed claiming that the “recovery and redemption” of the species is at hand, words which, even if they are cheerful, still implicitly accept the evolution-degeneration framing; and “Revival” giving an account of the ability of dedicated effort to morally uplift a community, but ending on a somewhat depressing note as it allows that some who have been uplifted will, inevitably, subside again: “Whatever is good in this great movement is unquestionably due to the Spirit of all grace, for no other cause is adequate to the production of such an effect… Whatever is evil is to be attributed to the infirmity and error of man.”

It was into this climate that The Ferrol Family set forth to have its effect on the morals of its readers. The context laid out here does not always related directly to the novel, but it offers an invaluable perspective on how certain events in the novel may be read in ways that are not at all obvious at first, particularly to readers of the 21st century.