[Peter Bayless] Evolution, Degeneration, Imagination: The Specter of Moral, Social and Physical Mutability in The Leisure Hour

pbayless

1880

Elizabeth Hely Walshe’s novel The Ferrol Family was serialized in the pages of The Leisure Hour between January 5th and March 29th of 1860. The novel is not a famous one or even familiar one--in fact, it is so obscure that chances are if one knows about it, one is either a particularly committed scholar of mid-century Victorian publishing or has happened across it through pure serendipity. There is by most standards nothing exceptionally remarkable in the text itself, at least when one considers it to those whom history has treated more kindly--the works of the Dickenses, Braddons, and Collinses, as it were, of the period. What does make The Ferrol Family interesting, for our purposes, are two facts, one deliberate and one an accident of history. The deliberate: The Ferrol Family was written for and bought by The Leisure Hour, a family magazine produced by the Religious Tract Society as a reaction to a perceived lack of wholesomeness in the magazines and publications of the day. Its inclusion in those pages constituted an endorsement by the sort of thinkers and gatekeepers who were attempting to frame and harness the moral imagination of mid-Victorian Britain. The accidental: The Ferrol Family’s run in The Leisure Hour took place less than two months after Charles Darwin’s seminal and famous work, On The Origin of Species, was published.

What resulted was a vignette of an intersection being played out across the educated society of the day between the decades-old moral imagination and the nascent scientific one. Though The Ferrol Family does not breathe a word of Darwin in its pages and only mentions medical science in passing, its themes demonstrate a fertile ground for the hybridization of the new evolutionary theory with extant fears of moral decay. The fears of degeneration thus produced in turn intersected with and reinforced pseudoscientific beliefs about race and criminality. These beliefs would continue to grow clearer and gain weight through the fin-de-siecle and beyond, but the pages of The Leisure Hour in the first months of 1860 offer a window into their germination, a glimpse all the more striking, once unearthed, for its innocent obscurity.

What resulted was a vignette of an intersection being played out across the educated society of the day between the decades-old moral imagination and the nascent scientific one. Though The Ferrol Family does not breathe a word of Darwin in its pages and only mentions medical science in passing, its themes demonstrate a fertile ground for the hybridization of the new evolutionary theory with extant fears of moral decay. The fears of degeneration thus produced in turn intersected with and reinforced pseudoscientific beliefs about race and criminality. These beliefs would continue to grow clearer and gain weight through the fin-de-siecle and beyond, but the pages of The Leisure Hour in the first months of 1860 offer a window into their germination, a glimpse all the more striking, once unearthed, for its innocent obscurity.

Aside: The Leisure Hour and the Religious Tract Society

|

The Religious Tract Society was formed by George Burder, a minister, in 1799, but did not expand out of its original eponymous function and into the market for periodicals until the 1820s. The Leisure Hour began publication in 1852 and aimed to compete with other, more secular and “melodramatic” magazines of its type. Like them, it featured as the centerpiece of each issue an installment of serial fiction, intended, however, to be of a “self-improving” rather than merely titillating or sensational nature; The Ferrol Family was only one in a long series of such pieces. Elsewhere, it featured columns on subjects that included popular science and history; these, however, secular or physical though they might be, were calculated to also be “of an uplifting character” (Lloyd et al.). The magazine that was synthesized out of these disparate and previously-profane sources reflected a larger shift in tactics on the part of the Society, wherein it adapted itself (or “evolved,” if one wishes to be cute) to meet the demands for popular entertainment and thus preserve the relevance and viewership of its message. As Beth Palmer writes, by the era of The Leisure Hour the Society had overcome both an “evangelical dislike” of fiction and its original, exclusively theological focus to provide both the serial fiction and the popular-science interest pieces with whose convergence this exhibit is concerned.

|

[Peter Bayless] Evolution, Degeneration, Imagination: The Specter of Moral, Social and Physical Mutability in The Leisure Hour

pbayless

1937

Context: The Degeneration Imagination

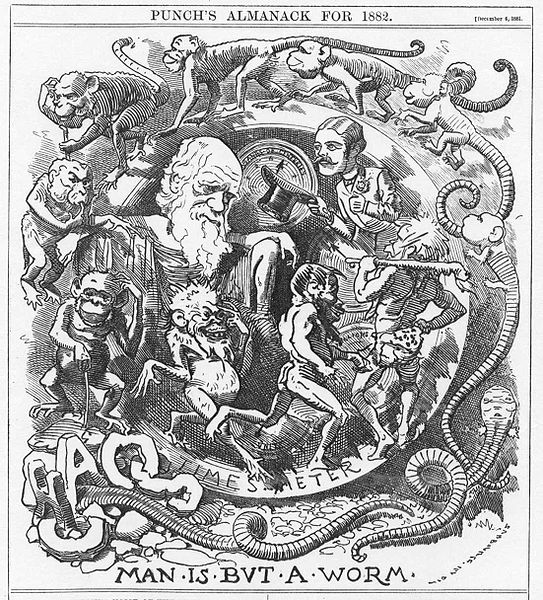

The abstract fears that came to be associated with scientific descriptions of degeneration have a long pedigree, of course--humans have been afraid of disease and death, and have been ascribing those same calamities (and many others) to divine agencies or to just retribution for immorality, for seemingly almost as long as written history has existed. It was during the nineteenth century, however, that the ‘rational’ or ‘physical’ sciences began to provide a compelling framework over which to drape these long-established moral fears. Charles Darwin's already-mentioned theory of natural selection, and similar ideas, stoked the fear of devolution even as they described its opposite: in order for natural selection to 'select,' for one group or entity to be 'chosen,' the thinking went, something else must be selected against--must be found unfit and thus die. Other, even more fundamental scientific descriptions of degeneration were being proposed in the form of the concepts of entropy and thermodynamics. As Chamberlain and Gilman write in the introduction to their anthology Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress, degeneration seemed like an indisputable, universal fact-- “people, nations, perhaps the universe itself” all grow old, die, and decay to dust (x). At the same time, the growing interest in scientific rationalism (or at least those portions of its discoveries that could be distilled for popular consumption) did not mean that superstition or supernatural dread disappeared overnight, as indeed they have not as we approach two centuries later. The Victorian generation was then one that had an increasing amount of apparently empirical verification for the religious idea that the visible world is not the ultimate reality, that the microscopic structure of the cosmos and (what we now call) the genetic could undermine the best-laid efforts of human beings. Small wonder, then, the popularity of the idea as reflected in pieces of news interest, cartoons, and other parts of the Victorian milieu. If there was one thing that both the theologically and scientifically minded of the day seemed to share, it was a preoccupation with narrative accounts of decline and fall. Degeneration, it seemed, offered something for everybody.

What was degeneration, precisely? Chamberlain and Gilman describe:

First of all, it meant to lose the properties of the genus, to decline to a lower type... to dust, perhaps, or to the behavior of the beasts of the barnyard. It also meant to lose the generative force, the force that through the green fuse drives the flower. (ix)

|

Fear of degeneration, then, encompassed a wide array of human phobias and aversions, any one of which, one imagines, could potentially trigger the association: fear of death, fear of becoming physically or cognitively disabled, fear of no longer being able to procreate or to see to one’s progeny as one would like. It was opposed to a “sanctity of types, or genuses, or species,” the social and moral implications of which will be seen when one realizes that this includes a comfort in the sense of belonging to one’s own racial, cultural or class group, and, as the authors mention, this belonging-to-category would become all the more frantically embraced the more uncertain it became (x). The more these fears grew, the larger a set of things took on a new meaning even if they might not have previously been associated, either implicitly or explicitly, with degeneration: fear of poverty, of different ethnic groups, of religious immorality. The scientific descriptions of evolution and its converses provided a “mode of coherence and continuity for the descriptions of phenomena” (xii). In other words, as Geoffrey Reiter puts it: degeneration was, firstly, terrifying because so many disparate fears could be subsumed under a single "aegis," and, conversely, was rhetorically useful because it was an indictment that could be applied to so many different things to "justify and articulate" the hostility towards them (218, 217).

|

|

As has already been alluded to, the use of degeneration as moral judgment had antecedents dating to long before a scientific language was developed to give it a greater (if spurious) sort of legitimacy. Eric Carlson notes that the core Christian doctrine of the Fall of Man, in the book of Genesis, is itself a story of medical affliction: to punish Adam and Eve for their sin of disobedience, God introduces a “bodily disposition towards illness and death and condemns future generations to this dismal bodily end” (Carlson 124). Likewise, Carlson observes that biblical stories of the taint of sin transmitting itself down through generations seemed to easily explain the observation that some chronic illnesses run in families. A preexisting association between morality and bodily health, or lacks thereof, thus already existed, and this association fitted neatly with the concept of degeneration as used by popular thought of the mid-19th century. It therefore comes as no surprise that the word carried moral weight and was used to condemn groups. In the case of other races--colonized populations, for example--evidence of degeneracy could be found in behavior and physiognomy alike. Native populations were seen as “morally underdeveloped” and this, in a pseudo-Darwinian misappropriation of the concept of environmental influence, was ascribed in part to the climate in which they made their homes; European colonists or soldiers, it was thought, could succumb to the same sort of “‘surexcitation of sexual organs’” arising from the tropic heat, and, combined with the bad influence of the natives themselves, could quickly become overstimulated, overindulged, and indolent.

|

|

Given the belief that ill moral, mental and social health themselves could be passed down to successive generations along with what were taken to be the physical markers of these maladies, among the many fears of degeneration was that of European societies themselves subsiding back into barbarism. If nature could cause an animal species to slowly lose viability and gradually be relegated to near extinction, so the thinking went, human races and kingdoms might likewise find themselves degenerating and being supplanted by others (102). The result was, at least at first, a perceived need to educate and police the society and individual in order to guide both to progress and away from decline. If virtues could be inculcated in the population, went this logic, the natural tendency towards degeneration could perhaps be averted (Nye 50-51). I believe that it is to this tradition that The Leisure Hour belongs, however subtly. The mission of the magazine and the Society, to socially and morally uplift were years or decades old in 1860, but the more recent idea of evolution had provided a useful framing rhetoric and a means of appealing to the reader with references to the exciting new science of the day. It is worth noting that at this early stage the specter of degeneration appears somewhat nascent and more subtle: like the ghosts in Dickens's A Christmas Carol, it is alluded to in order to warn, with the implication that disaster may be averted--that evolution rather than devolution may take place, whether racial, moral or societal. Later in the century, the idea of genetic degeneration would become much more entrenched in the popular understanding of history and the perception of the city as a place for opportunity and upward mobility would turn into one of a “breeding ground” for the subhuman “residuum” (64-65), but The Ferrol Family belongs, chronologically and in spirit, to a philosophy that hoped to uplift the working and middle classes.

|

The Leisure Hour did not necessarily batter its readers over the head with its moral messages outside of its fiction, at least not during the run of The Ferrol Family (the serial novel itself is arguably another matter). Nor did it explicitly connect, during this period, the pseudoscientific idea of degeneration with the moral decay it stood as a bulwark against. But instead, perhaps, it followed the same strategy in scientific education as it did in morals: subtly 'uplifting' readers with articles designed to appeal to their intellectual curiosity about the scientific developments of the day, carefully selected and presented so as to convey a sense of superiority and progress over previous epochs of history (and their supposed contemporary analogues). We would expect to find articles on popular science and society alike praise moral progress or warn against downfalls on a societal or biological level, or that encourage readers to take an interest in the sort of science that underlay these attitudes. A quick look at the magazine’s other content during the novel’s run supports this hypothesis. Two separate pieces entitled “Man among the Mammoths”-- one an article in its own right, another, later one a blurb in the Varieties column--appealed to an apparently current interest in biological and anthropological history, using tales of finds in the soil strata of England to invite readers to take pride in their own geographical origins, while disagreeing on whether exactly mankind actually lived among the mammoths. “Multiplication of Species,” also in the Varieties column, namedropped the then new and exciting Charles Darwin and his book, showing that such were supposed to be recognizable and of interest to the common reader. “A Night with the Ethnologists” featured the correspondent attending a scientific talk and reporting on the recently unearthed exotic skulls he had been privileged to witness firsthand, skulls for which the term “crania” was used as metonym and the precise cranial features of which were hypothesized to be directly correlated with their prior owners’ level of civilization. Finally, “Past versus Present” and “Fruits of the Revival in Ulster” both presented rosily optimistic views of the human capacity for evolution; “Past”’s author flatly rejecting the notion that the human race is degenerating and indeed claiming that the “recovery and redemption” of the species is at hand, words which, even if they are cheerful, still implicitly accept the evolution-degeneration framing; and “Revival” giving an account of the ability of dedicated effort to morally uplift a community, but ending on a somewhat depressing note as it allows that some who have been uplifted will, inevitably, subside again: “Whatever is good in this great movement is unquestionably due to the Spirit of all grace, for no other cause is adequate to the production of such an effect… Whatever is evil is to be attributed to the infirmity and error of man.”

It was into this climate that The Ferrol Family set forth to have its effect on the morals of its readers. The context laid out here does not always related directly to the novel, but it offers an invaluable perspective on how certain events in the novel may be read in ways that are not at all obvious at first, particularly to readers of the 21st century.

[Peter Bayless] Evolution, Degeneration, Imagination: The Specter of Moral, Social and Physical Mutability in The Leisure Hour

pbayless

1881

Do This, Not That

The Ferrol Family tells the story of the eponymous extended family who, almost to a man or woman, serve as models for the sort of moral concern that the Leisure Hour wished to impart to its readers. Thematically, the novel concerns itself with the problem of excessive vanity and of fiscally imprudent living, as reflected in the novel’s subtitle of Keeping Up Appearances, and particularly as these problems motivate its characters to commit immoral and or criminal acts in order to hold on to their lifestyles when their chosen “appearances” prove to exceed the reach of their pocketbooks. Roughly speaking, the characters are divided into two predictable camps: those who resolve to live fiscally temperate lives and thus serve as positive models, and those who allow their appetites to get the better of them and are thus, in the just world spun by Walshe with her editors’ blessing, headed for downfall. In at least two of the cases, the downfall in question is directly linked to the fear of sickness and physical infirmity, and in at least a third it intersects with the framework of nascent social Darwinism.

Mr. Hugh Ferrol

|

If there is a pyramid of economic hubris in The Ferrol Family, then surely Hugh Ferrol (the eldest of a surprising variety of Hughs who populate the book) is at its apex. An irresponsible financier whose unwise investments have led his firm into “hopeless insolvency,” Hugh’s response to his potential embarrassment is to begin attempting to coerce his son Euston into marrying a woman who will bring with her a personal fortune of sufficient size to cover the family’s liabilities.

Before he can overcome Euston’s determination to instead marry for love, Mr. Ferrol is struck by an apparent stroke, and in a highly significant move on the author’s part, his temporal and economic power is taken away via the simultaneous robbing of his physical agency; “the hand which could yesterday have signed away thousands,” writes Walshe, “lay helpless and aimless as an infant’s” (19). A physical degeneration, superficially similar to that of advanced age but effected overnight instead of “by the lapse of a score years,” has overtaken the elder Ferrol: “The face was drawn and withered. . . the eyes hollow, the lips shrunken.” The effect on an observer, in the purpose of Euston, is--if one follows where the Leisure Hour’s moral finger is pointing, and Walshe does--to be confronted with the inherent infirmity and impermanence of earthly flesh: |

Euston shuddered. Like all others who have their portion in this world, the necessity of leaving it was invariably put far from his thoughts; but here the idea was forced upon him--thrust under his very eyes. He had a sensation, as if standing upon the edge of some utter darkness, and looking into its rayless depths, blindly. Beyond the narrow ledge of life, on which that nerveless form lay, he saw neither help nor hope! (19)

Euston is briefly saved from having to confront this reality by, ironically, the return of the medical men, who offer some temporary hope for his father. But Mr. Ferrol’s collapse is inevitably, if not immediately, fatal, and many pages later the novel’s eye returns to him to witness his final decline and death:

His hair is thinner and whiter since we saw him last--of that withered bleached hue, which differs as much from the “glorious” hoary head of healthful age, as doth the fruit decayed at core from the ripe richness of perfect maturity. The once firm lines of his mouth have been touched with some helpless indecision: over his whole figure was an air of wavering and weakness. (51)

Confronted with this entirely unsubtle selection of degeneration imagery arrayed against him, the elder Hugh Ferrol attempts to cling to hope on more or less the same terms, wishing for regeneration and physical improvement, bolstered by the hopes of medical science. “I soon shall be [able to attend to business,” he says: “did not Doctor Proby say so?” (51). Minutes later, he declares, “I think I walk better than I am yesterday. . . I think I am better” (52).

We can only conjecture as to what the outcome of his case might have been, in the world of the novel, if he had been willing to accompany his wishes for physical reinvigoration with a commitment to a spiritual one. As it happens, he does not, and so his fate is the predictable one. And as the descent into death is described in increasingly abstract terms, the novel takes a parting shot at the men of science:

Come, science, thou art powerful; build up the shattered tenement again; even for a week--a day--an hour, retard the final dispossession! What! mute to the appeal, standest helplessly beside the unequal struggle! O poor soul; poor, blind, groping soul, tottering on the verge of a black infinitude. (67)

The relationship between the moral alarmists and science thus ends on an amusingly mercenary note: science is useful when its language or theories can be used to stir up alarm, but power to resolve the fears it causes is still held out of its grasp. One might be reminded of more recent moral panics surrounding biological bogeymen, such as the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s!

Dr. and Mrs. Hugh Ferrol

If the purpose of the elder Mr. Hugh Ferrol is to caution readers against being willing to morally compromise themselves in order to maintain a high social standing, then the tale of the confusingly named (and, as mentioned, still not the last of the book’s Hughs) Dr. Ferrol is a cautionary one against not reaching too high in the first place. An-up-and-coming doctor who is attempting to cast himself as a city physician, ministering to the relatively affluent classes rather than the book’s implied alternative of becoming a more humble doctor to the poor or rural dwellers, “Dr. Hugh” soon learns--or perhaps unwisely decides, led astray by the influence of his social-climbing mother and other family members--that to “keep up appearances” of the proper sort for a higher-class doctor requires paying rent in the city, retaining a fancy carriage and coachman, and any number of other things that together combine to make him and his wife live above their means. When a crisis looms, Dr. Hugh eventually submits to the temptation to forge his brother-in-law’s signature on a bank-bill in the hopes that he can pay it back himself before it comes due. The offended party, Mr. Wardour, learns of the forgery but decides, in a model of Christian charity, to cover the bill himself. The law, when the debts catch up with the doctor anyway, is not so charitable, and soon Dr. Hugh finds himself jailed while his case awaits judgment.

Here the ‘punishment’ of Dr. Hugh for his intemperance takes two distinctly different, and successive, stages, both of which play upon the fear of a Fall. First, the nights that the doctor spends jailed take the form of a vision in which the torments of Hell are paraded in front of the sinner. The jail is a bedlam or inferno of noise, “peals of laughter” and “comic songs” filling its “dismal stone passages” (181); however the author tries to tell us that the residents are “far from despondency,” it is difficult to see their mirth as in any way enviable or other than pathetic. Dr. Hugh asks who his raucous neighbors are, and is told,

“In thirty-two, sir? The celebrated Mr. Swyndle, sir, that failed for ninety thousand a fortnight since; you may have heard of Swyndle and Co., sir, the affair made a great noise. All the papers full of it. A very agreeable gentleman, sir--very agreeable.”

As the author helpfully clarifies, the turnkey clearly has “a species of professional respect” for this great man.

While it is hardly necessary to have the models of Darwin in order to remonstrate against a career of financial risk, the rapidly changing complexion of the public imagination at this time could not have helped but color the image of the unsubtly named Mr. Swyndle (the modern meaning of swindle was already current in 1860). What Walshe offers the reader is a glimpse of natural selection perverted: accepting the axiom that the fittest will rise to the top, she dives to the core of The Ferrol Family’s moral by reminding that ‘fittest’ must be properly defined as well. What leads to economic evolution may yet bring into the bargain moral and societal degeneration. Swyndle and his partners, along with the elder (and now deceased) Mr. Hugh Ferrol, have displayed traits that are in some sense selected for: the ability to make money, perhaps, or simply to “make noise” in the papers (and, cleverly, in their jail cells). Walshe shows--perhaps unconsciously--how an organism, to use the Darwinian metaphor, can appear to thrive yet ultimately prove maladapted.

If the preceding seems to be getting somewhat too abstract, then never fear; the family of Dr. Hugh receives its punitive downfall in the physiological sense as well. Here it is not the sinner himself whose vitality fails, but his wife’s instead, in a Biblically cruel twist (literally: the displacement of moral punishment onto the innocent reminds one of the death of David and Bathsheba’s child). Dr. Hugh has, as summarized by the story, done what society expects of him; he has gone through the “usual stages” and “due course” of legal recovery from insolvency (193); and, released from the court at last, he goes home to find his wife sickened and dying: not from any primarily physical malady, but from the sheer weight, or “shock,” of the legal and financial humiliation.

She had never been able to visit him in prison; the shock received on that last morning in their own home [when the officers came to arrest her husband] had been too much for her strength. Great weakness had seized her in nerve and limb. (194)

As her husband bemoans and Agatha does not fully deny, he has been a “blight on her life”; the term is something more than a figure of speech here, as his misdeeds cause her (however improbably) to waste away and die as surely as any more physical illness. The punishments for the crimes of Dr. Hugh are thus reified in the flesh at last, just when one is thinking we might escape the novel without anyone else paying more than the legal or pecuniary penalties for their sins. Smacking of authorial fiat as it does, this conclusion to the story neatly revisits the fear, newly substantiated by pseudoscience, of the link between moral and physiological ill-fortune.

Conclusions: Meaning in Obscurity

The Ferrol Family did not itself instigate or represent a watershed moment in the "evolution," so to speak, of Victorian moral or scientific thought. However, it and its context in the Leisure Hour offer an interesting and perhaps useful look at the genesis of a popular intellectual trend that would, as described above, become more concrete as the mid-century gave way to the fin-de-siecle. They show that in 1860, the readers of a periodical whose primary audiences included the working or servant class could be expected to not only understand, but be curious about, anthropological and biological theories of the day; furthermore, that these theories were implicitly seen as 'uplifting' by the moral gatekeepers on the publication's editorial staff and that they were correlated with moral lessons in the fiction that ran alongside them. If the correlations are in some ways still nascent, subtle and obscure, then, like the famous Galapagos finches of Darwin himself, they may still point us in a useful direction.

[Peter Bayless] Evolution, Degeneration, Imagination: The Specter of Moral, Social and Physical Mutability in The Leisure Hour

pbayless

1893

Works Cited

Textual Sources

“A Night with the Ethnologists.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 19 Apr. 1860: 244-246. Print.

Carlson, Eric T. "Medicine and Degeneration: Theory and Praxis." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. 121-144. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

"Degeneration: An Introduction." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. ix-xiv. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

“Fruits of the Revival in Ulster.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 1 Mar. 1860: 142-143.

Lloyd, Amy, and Graham Law. “Leisure Hour(1852-1905).” Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism(2009). C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. Web. 11 May 2013.

“Man among the Mammoths.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 19 Jan. 1860: 37-39. Print.

Palmer, Beth. “Religious Tract Society.” Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism(2009). C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. Web. 11 May 2013.

“Past versus Present.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 19 Apr. 1860: 255-256. Print.

Nye, Robert A. "Sociology and Degeneration: The Irony of Progress." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. 49-71. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

Reiter, Geoffrey. “‘Travelling Beastward’: George Macdonald's Princess Books And Late Victorian Supernatural Degeneration Fiction.” George MacDonald: Literary Heritage and Heirs: Essays on the Background and Legacy of His Writing. 217-226. Wayne, PA: Zossima, 2008.

Stepan, Nancy. "Biological Degeneration: Races and Proper Places." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. 97-120. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

“Varieties. – Man among the Mammoths.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 26 Jan. 1860: 64. Print.

“Varieties. – Multiplication of Species.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 2 Feb. 1860: 80. Print.

Walshe, Elizabeth Hely. The Ferrol Family. The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 5 Jan. 1860 – 29 Mar. 1860. Print.

Carlson, Eric T. "Medicine and Degeneration: Theory and Praxis." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. 121-144. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

"Degeneration: An Introduction." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. ix-xiv. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

“Fruits of the Revival in Ulster.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 1 Mar. 1860: 142-143.

Lloyd, Amy, and Graham Law. “Leisure Hour(1852-1905).” Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism(2009). C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. Web. 11 May 2013.

“Man among the Mammoths.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 19 Jan. 1860: 37-39. Print.

Palmer, Beth. “Religious Tract Society.” Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism(2009). C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. Web. 11 May 2013.

“Past versus Present.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 19 Apr. 1860: 255-256. Print.

Nye, Robert A. "Sociology and Degeneration: The Irony of Progress." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. 49-71. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

Reiter, Geoffrey. “‘Travelling Beastward’: George Macdonald's Princess Books And Late Victorian Supernatural Degeneration Fiction.” George MacDonald: Literary Heritage and Heirs: Essays on the Background and Legacy of His Writing. 217-226. Wayne, PA: Zossima, 2008.

Stepan, Nancy. "Biological Degeneration: Races and Proper Places." Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress. Ed. J. Edward Chamberlin and Sander L. Gilman. 97-120. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. Print.

“Varieties. – Man among the Mammoths.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 26 Jan. 1860: 64. Print.

“Varieties. – Multiplication of Species.” The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 2 Feb. 1860: 80. Print.

Walshe, Elizabeth Hely. The Ferrol Family. The Leisure hour : a family journal of instruction and recreation. 5 Jan. 1860 – 29 Mar. 1860. Print.

Images

"Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde poster." <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dr_Jekyll_and_Mr_Hyde_poster.png> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 25 April 2013.

"Fig. 1 William Rimmer, Elements of Design, (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1894), plate 9. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester." <http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring_03/articles/gr/davi_1b.jpg> Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide: a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture. Web. 24 April 2013.

"Fig. 1 William Rimmer, Elements of Design, (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1894), plate 9. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester." <http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring_03/articles/gr/davi_1b.jpg> Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide: a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture. Web. 24 April 2013.

"FIG. 19.—From a photograph of an insane woman, to show the condition of her hair." <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Expression_of_the_Emotions_Figure_19.png> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2013.

Index. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 1 Jan. 1852: 1. Print.

Index. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 1 Jan. 1852: 1. Print.

"Johan Friedrich Blumenbach 1752 - 1840." <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Johann_Friedrich_Blumenbach.jpg> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2013.

"Man is But a Worm."<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Man_is_But_a_Worm.jpg> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2013.

"Mother Nature casting evils out of her children." <http://www.isis.aust.com/stephan/writings/sexuality/images/nature.jpg> Isis Creations. Web. 25 April 2013.

"Ominous reception of his son and daughter-in-law by old Mr. Ferrol." The Ferrol Family. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 26 Jan. 1860: 49. Print.

"Tell her that our firm is insolvent, and will be in the Gazette before a week." The Ferrol Family. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 12 Jan. 1860: 17. Print.

Title page. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 1 Jan. 1852: 5. Print.

“Passing Away!” The Ferrol Family. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 29 Mar. 1860: 193. Print.

"The Irish Frankenstein." <http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/rickard/J.jpg> Web. 24 April 2013.

"Man is But a Worm."<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Man_is_But_a_Worm.jpg> Wikimedia Commons. Web. 24 April 2013.

"Mother Nature casting evils out of her children." <http://www.isis.aust.com/stephan/writings/sexuality/images/nature.jpg> Isis Creations. Web. 25 April 2013.

"Ominous reception of his son and daughter-in-law by old Mr. Ferrol." The Ferrol Family. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 26 Jan. 1860: 49. Print.

"Tell her that our firm is insolvent, and will be in the Gazette before a week." The Ferrol Family. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 12 Jan. 1860: 17. Print.

Title page. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 1 Jan. 1852: 5. Print.

“Passing Away!” The Ferrol Family. The Leisure Hour: a family journal of instruction and recreation. 29 Mar. 1860: 193. Print.

"The Irish Frankenstein." <http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/rickard/J.jpg> Web. 24 April 2013.