A Deconstruction of Victorian Gender Identity through the Lady of Shalott

Meaghan Munholland & Matthew Wright

Ryerson University

1338

|

Waterhouse also explores the idea of a fallen woman in his painting. He paints the Lady of Shalott in white, staying true to Tennyson’s text, which is symbolic of her former innocence and angelic status. The Lady’s hair, however, juxtaposes the "goodness" of her white dress. Waterhouse paints the Lady with her hair down, in its untamed natural state. Other Waterhouse paintings, which depict the Lady in her tower, are shown with the Lady’s hair up, styled and tidy. This signifies that while she is imprisoned she is moral and refined, yet when she exposes herself to the external world to which she was denied, she is unruly and uncontrolled. To Victorian viewers, untamed hair was a marker of uncontrolled sexuality@Barzilai 242. which again illustrates the Lady of Shalott as being constructed as a sexual being commencing at the end of Part 2 of Tennyson's text. |

The depiction of the Lady of Shalott in both Tennyson's poem and Waterhouse's painting are derived from a patriarchal idealization of an idealization. That is, the Lady herself idealizes precisely what a patriarchal male would want her to idealize, in order to fulfill his own idea of the perfect female. This plays into a perverse pleasure that the stereotypical Victorian male reader would have derived from the protagonist’s suffering. John William Waterhouse was at the tail end of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, which was a response to the more posed, formulaic styles of the Renaissance-inspired Mannerists, like Raphael and Caravaggio. Pre-Raphaelites are known for taking inspiration from Romanticism and Medievalism, which they believed enabled the strongest emotional response from their viewers. This is part of what makes Waterhouse's The Lady of the Shalott so appealing to the Victorian man; like a modern Hollywood film, the characters are designed to be extra-ordinary, the product of fantasy rather than reality. This is precisely the intention of both Waterhouse and Tennyson, to mythologize a female character who is the visible personification of absolute perfection, and then to add the heart-wrenching twist of impending tragedy. Waterhouse painted The Lady of Shalott with idealized proportions, using colours accentuated to 'pop', in order to establish the impression of an uncanny, dream-like state.

|

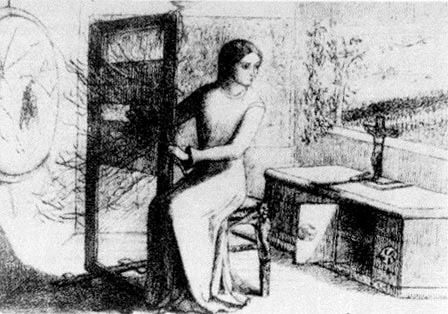

In contrast to Waterhouse’s lavish oil on canvas painting, Elizabeth Siddal’s 1853 pen and ink on paper illustration titled The Lady of Shalott at Her Loom explores the female perception of the title character. Siddel uses unadorned techniques to represent the Lady of Shalott which mirrors the Lady’s gray and bland existence in her tower. It is also interesting to note that Siddal’s visual work was created thirty five years prior to Waterhouse’s painting. This demonstrates the evolution of the visual interpretation Tennyson’s poem through a gendered, but also historical lens. The simplicity of Siddal’s medium demonstrates that a female artist does not see the Lady as an idealized and extra-ordinary fantasy but rather as a lonely woman who longs for something beyond her current situation. Siddal also perceives the Lady as a moral figure as the artist’s illustration prominently displays a crucifix, which is not present in Tennyson’s poem. Arguably, many Victorian females would have empathized with the Lady of Siddal's visual work as an imprisoned and isolated woman. They would have championed her attempt to free herself from her repressive constraints and pitied her when she fought and lost the battle over her own destiny. |

Between Tennyson’s poetry and Waterhouse’s painting is an interesting inter-textual communication that is alluded to in a series of satirical sketches that were published in the same year the painting was first unveiled to the public. Pictures at Play, or Dialogues of the Galleries,@Andrew Lang, William Ernest Henley and Harry Furniss, Pictures at Play, or Dialogues of the Galleries (New York: AMS Press, 1970) Print. written by art critics Andrew Lang and W.E. Henley, and illustrated by Harry Furniss, brings Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott to life as a speaking character who interacts with other paintings in an art gallery and sings reflectively about her own conception and depiction as a piece of art. In Act V of the play, she mentions a connection between her and Victorian realist painter Jules Bastien-Lepage,@Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V. whom Waterhouse took stylistic inspiration from, painting the Lady with similar blocks of colour and thick brush strokes characteristic of Lepage's style. The Lady communicates with another female character in a Sir Frank Dicksee painting, whom the Lady calls "Little Dicksee," envying her for having been depicted in an "age of innocence."@Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V. This character of purity incarnate tells the Lady of Shalott that she is deceived; she expresses that there is a secret sadness in herself as well. Similarly, the Lady points out that she has been dismissed by some critics as simply the work of "an excessively rising young Associate"@Lang, Henley and Furniss Act V. instead of as the victim of unrequited love, posing shortly before her death. This further explains the necessity of a context within the painting; without an understanding of Tennyson's poem, Waterhouse's Lady becomes an entirely different character. It is the viewer of the painting who enables it, through his/her own subjectivity. In this way, inter-textuality plays an essential role in establishing the Lady's character in Waterhouse's work. The more these paintings and poems communicate with each other, the greater their meaning and aesthetic response becomes.The satirical verses of Pictures at Play demonstrate the self-awareness of the Lady as an icon of female objectification. She recognizes that she has been doomed both by Tennyson and Waterhouse, to be immortalized in a state of glorified despair. This is because the painting is a response to the aesthetic ideals prescribed by the poem. Therefore, it is the background knowledge of the viewer that enables them to derive that the Lady is the product of patriarchal social values which expect women to be subservient and everlastingly faithful to their male counterpart, even when he is unattainable. And in Pictures at Play, it is this implied understanding that personifies the Lady into a talking character.

Although Tennyson and Waterhouse's works were created over half a century apart, the objective of both poem and painting was to express a fundamental disconnect between the facts of reality and the transcendence of idealization. The Lady herself seems to stem from the perverse male idealization of an entirely faithful female admirer, who literally submits herself as his romantic slave. Despite the artistic and literary advancement throughout the Victorian era, it is clear through the examination of both Tennyson and Waterhouse's works that the portrayal of femininity remained relativity static. Both text and painting depict womanhood as something to be idealized, but also something to be punished if an attempt is made to subvert male dominated, societal norms. The initial emotional response of serenity and idyllic beauty is fundamentally deceptive. In order to fully appreciate the Lady of the Shalott, the viewer/reader has to experience disappointment at some level, to realize the Lady's sadness peaking through the otherwise perfect scene. This creates an interesting parallel between viewer/reader and subject matter - just as the Lady experiences the misery of an intrinsic lack of fulfillment, so must the textual and visual audience, who must accept the imperfection of the scene. This is part of what makes the Lady of the Shalott so endearing - that above all, the emotional effectiveness of her character relies on an aesthetic response of empathy between her and the audience.