The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

You are here •Page 3 •Page 4 •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 3 •Page 4 •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

1890

"Hear the Tolling of the Bells"

"The Chimes" by Charles Dickens, 1844

The National Gallery, London

|

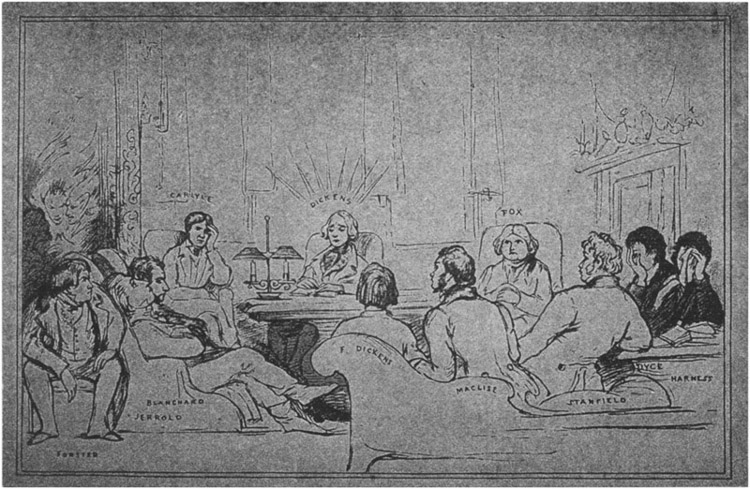

Daniel Maclise, 1844

Project Gutenberg

|

While most Dickensian scholars are very familiar with Dickens' most famous Christmas story, The Christmas Carol, very little scholarship has been done on his lesser known Christmas novellas. Despite being popular, the Carol was a financial failure for Dickens. He found financial success with the publication of four additional Christmas books in each of the following four years. The second of these was titled The Chimes, A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. In the introduction to a rare American printing of the complete version of The Chimes with pictures, H.S Nichols notes that Dickens began writing the story in Genoa@This date and location is also when and where Dickens was treating Madame de la Rue (Willis & Wynne)., where he found inspiration in the bells that rang through the city (v). He found them to be maddening, which inspired him to create the character of Trotty Veck, who loves the bells, but also goes mad from their constant sounding. Philip V. Allingham, contributing editor to the Victorian Web, notes that after Dickens finished writing the novel on November 3, 1844, he quickly returned to London to oversee the printing. On December 3, he gathered an eclectic group of friends and liberals, some of whom were inspirations for the book, for a reading. These friends included, among others, Thomas Carlyle, John Forster, and Daniel Maclise (Nichols vi-vii). Maclise memorialized the gathering in an iconic sketch reminiscent of “The Last Supper.”

|

|

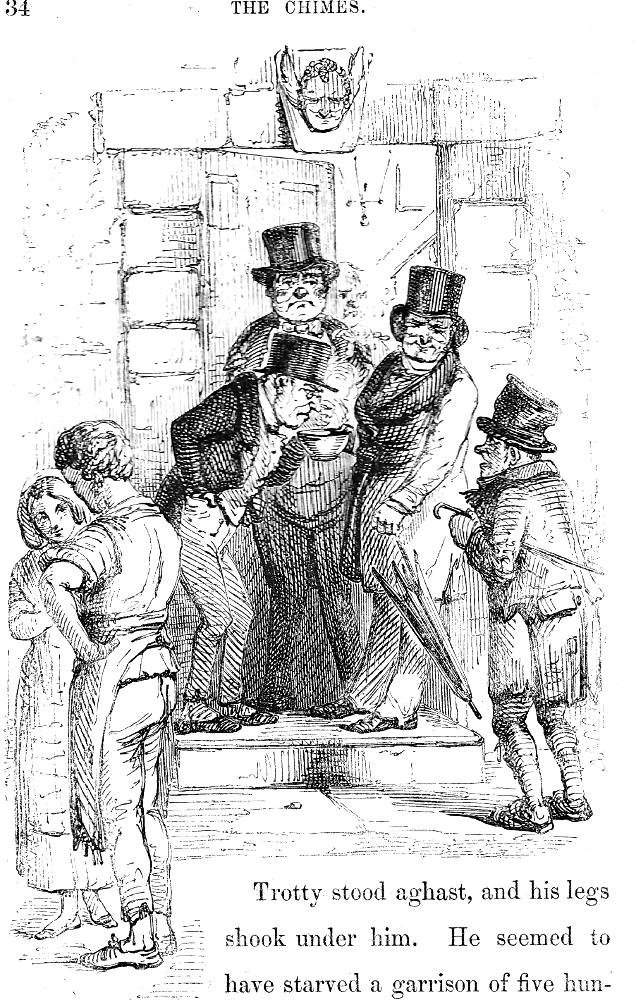

The story centers on the character of Trotty Veck (properly known as Toby or Tobias). Trotty is a poor widower and a self-employed messenger. He has an adult daughter, Meg, who is soon to be married. The story begins on New Year’s Eve and is divided into four quarters. In the first two quarters, Trotty encounters two groups of middle-class men and hears their unfortunate opinions of the working class. A hard-nosed gentleman declares, “The good old times, the grand old times, the great old times! Those were the times for a bold peasantry, and all that sort of thing” (37). When the middle-class men hear of Meg’s impending marriage, one gentleman immediately contends that the poor have no business getting married. Another of these gentlemen, Alderman Cute, goes through a list of working-class people he intends to “Put Down” including single women, boys, suicide victims, widows, and so on. Clearly, in The Chimes, the middle-class are not pleased with the poor, including Trotty and his family.

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

American Edition Edited by H.S. Nichols, 1914

|

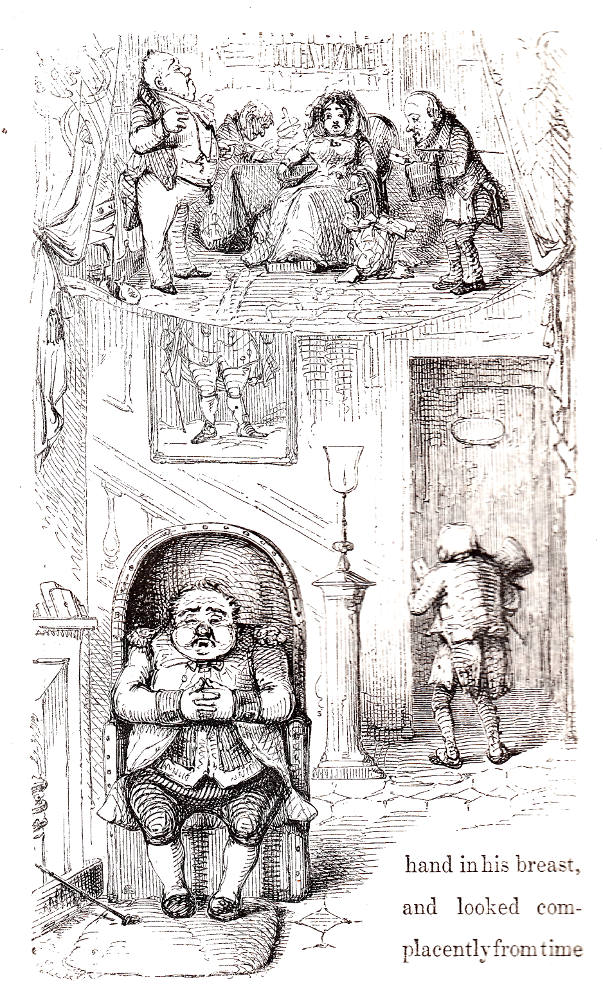

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

While this book was certainly intended to be a Christmas book, a book primarily for profit, Dickens is very clearly offering a moral message. The book was very popular, a financial success, and cause for much debate after its printing. Allingham argues the reason The Chimes may have fallen out of favor as time has passed is because it is was intended to be a satire, and it is difficult for modern readers to understand it as such. Allingham points out that the 1840s were known as the “hungry forties,” and there were many events the English would have been well acquainted with (1847 potato famine, a revolutionary movement known as Chartism, riots by laborers in Manchster, rick-burning by agricultural laborers in Dorset, and rampant prostitution), and therefore would have easily read The Chimes as a social statement. Further supporting this view, Michael Slater argues the novella was heavily influenced by the ideas of Thomas Carlyle, a prominent advocate for the Chartist movement. Slater notes that both Dickens and Carlyle felt there was an impending social revolution. Moreover, they were very concerned about the “widening gap between the rich and the poor” (507). This concern is very evident in the first two quarters of The Chimes, where the working-class characters receive full character development, whereas the middle-class characters are merely used as props or stereotypes. Readers of The Chimes immediately bond with Trotty and see him as the hero of this tale.

|

|

Unfortunately for Trotty, all the middle-class chatter he overheard, regarding the poor being born bad, sinks into his subconscious. Trotty laments, “We seem to do dreadful things; we seem to give a good deal of trouble…we have no right to a New Year” (18). As he begins to internalize the persecutory messages of the middle-class, his beloved bells begin to turn on him. As they chime he hears, “Put ‘em down, Put ‘em down! Good old Times, Good old Times! Facts and figures, Facts and figures! Put ‘em down, Put ‘em down!” (49).

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

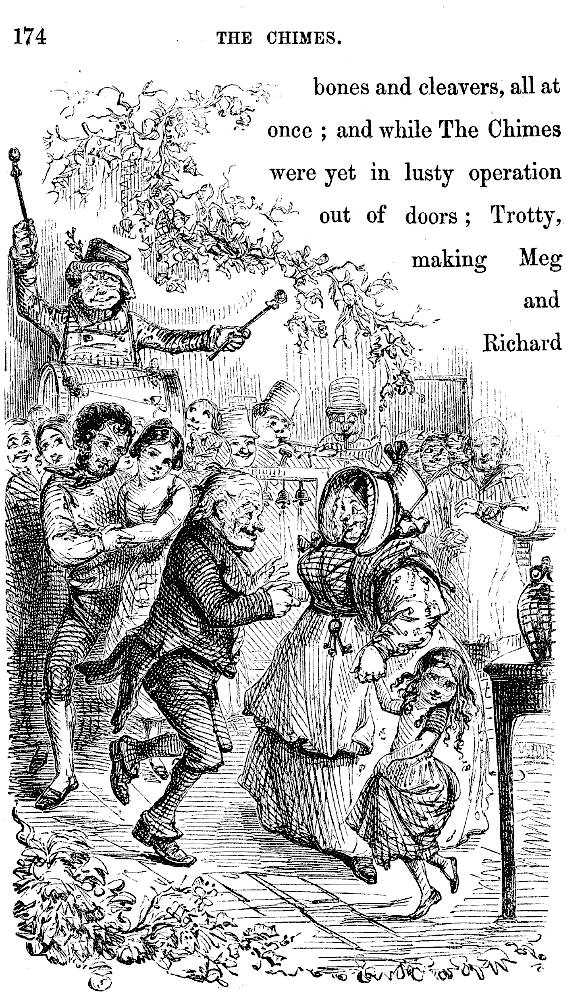

In the third quarter, Trotty is drawn in by the bells, who intend to teach him a lesson about his newly formed opinions. When he enters the tower he sees it is “swarming with dwarf phantoms, spirits, elfin creatures of the Bells” (96). These creatures transform him into a dreamlike state, where he believes he died nine years previous, and is accompanied by a child spirit to see how his daughter is faring (reminiscent of the Carol’s Ghost of Christmas Past). Unfortunately, we find in the fourth quarter, because she never married and instead lived a life according to the beliefs of the middle-class men, her life has not turned out well. The bells demand that Trotty learn a lesson from the one person closest to him in life. He of course promises that he has learned his lesson, and he eventually wakes only to realize that it has all been a dream and is forever a changed man.

|

|

There are a myriad of fantastical creatures in this story, taking the spirits in the Carol a step further. In the tower, there are, as can be seen in the illustrations, cherubs, ghouls, demons, ghosts, and more. Moreover, in the dream sequence, Trotty is a ghost, along with his spirit-child companion. As has been established, ghost stories were a popular genre during the Victorian Christmas. Dickens, however, prefers to make the ghosts in his ghost stories moral lessons. As will be seen in a Gaskell ghost story found in Household Words, this formula does not hold true for all writers of Christmas or Gothic ghost stories. The Dickensian formula revolves around a central character that needs to learn a lesson, which he learns with the help of spirits; spirits that appear in a dream-like state, and spirits that only he can see. This formula could be symptomatic of his general skepticism surrounding ghosts. In his introduction to a collection of all five Christmas books, Douglas-Fairhurst writes, "Dickens, who, like many of his contemporaries, routinely mocked the belief in ghosts as a lingering trace of the uncivilized past, but also found it impossible to shake more primitive feelings of dread out of his mind or voice" (xiii). Dickens was able to appeal to the genre of ghost stories through his dream-state formula, while remaining distant to the idea of ghosts as a conscious reality.

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

Despite having fallen out of popularity, modern readers may actually find familiarity in the story. There are several theories as to where Dickens found inspiration for The Chimes as well as who Dickens inspired with this novella. The bells in Genoa may not have been Dickens' only inspiration. Marilyn Kurata argues that Dickens also found transatlantic inspiration in the figure of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Kurata notes that, upon his return from America in 1842, he gave his close friend John Forster a copy of Moses from an Old Manse (10). In this collection, Hawthorne included “Young Goodman Brown,” written in 1835, nine years prior to the writing and publication of The Chimes. Kurata finds similarities in the hero of the stories: night journeys, fantastical visions, and innocents that lose their faith (11). Although the heroes do seem to follow a pattern, the purpose and effects of each are drastically different, with “Brown” being vastly darker and arguably scarier, and The Chimes more of an uplifting moral message. While the similarities are hard to dispute, Kurata’s observations seem to locate a vague similarity in the story lines.

|

|

If Dickens was influenced by an American author, he certainly paid the favor back by being a significant influence for Edgar Allan Poe. If a reader is at all familiar with Poe’s “The Bells,” the possible connection between the two works is evident within the first few pages of The Chimes. The melodious tone and specific phrases can be linked directly to Poe’s poem. One such familiar line occurs when the narrator of The Chimes declares the bells are “high up in the steeple!” (4). These connections continue throughout the novel in various instances including: “Up, up, up; and climb and clamber; up, up, up; higher, higher, higher up!” (92), “…heard them howl” (97), “he saw them representing, here a marriage ceremony, there a funeral; in this chamber an election, and in that a ball; everywhere, restless and untiring motion” (97), “..uproar of the bells” (97), and “Goblin of the Bell” (100). Another obvious similarity is the structure, both being in four quarters. These claims are further strengthened in an article by Burton Pollin. Pollin notes that Poe had a deep reverence for Dickens, despite Dickens' refusal to give Poe publishing favors. Moreover, Pollin provides proof that Poe certainly had an opportunity to read The Chimes before writing “The Bells.” The Chimes was printed, without Dickens' consent, in the New-York Evening Mirror on Jan 28, 1845, printed in the space just before Poe’s “The Raven.” Pollin also points to a now lost book, published by a close friend of Poe, Frederick W. Thomas, upon Poe’s death. Before it was lost, some transcriptions quote Thomas as saying that The Chimes was Poe’s final inspiration for “The Bells.”

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

While many modern readers, even Dickens enthusiasts, may have previously overlooked The Chimes in Dickens' great body of works, it still stands as an important contributor to Dickens’ place in history as Father Christmas.