The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

•Page 3

•Page 4

•Page 5

•Page 6

You are here •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

1886

Becoming Father Christmas

Ten years after his festive ghost story first went to press, Dickens began a tradition which his great-great grandson, Gerald Dickens, continues to this day. This tradition has caused A Christmas Carol to leave an indelible impression on the world: public readings. Dickens had a life-long love of performing. In her article examining Dickens' early performing life, Leigh Woods notes that Dickens held twenty-three roles as an actor between the ages of twenty-one and forty-five, performing in theatrical productions until 1857 (90). Just a few years before the end of his acting career, in 1853 Dickens gave his first public reading of A Christmas Carol. According to Douglas-Fairhurst, this reading opened up a new outlet for Dickens to share with his audience. Consequently, he gave 127 readings of the Carol from this date until his death in 1870 (xxviii).

Charles Dickens Reading

Charles A. Barry, via Wikimedia Commons

|

Gerald Dickens

Wikimedia Commons

|

1858 Reading Tour

Wikimedia Commons

|

In 1857, the final year of his acting career, Dickens first read the Carol to a London audience. According to a London Times article (later reprinted in the American Littell's Living Age), this first London reading was met with great success. The article writer notes that his audience was, "in a state of breathless interest" during the two hour reading (544). Also in this review, the writer observes that Dickens does not try to impersonate any character, with the exception of Scrooge, whom he impersonates with "senile accents" (544). Woods claims that much can be learned about Dickens'readings based on his choices and casting as an actor. She argues that Dickens often played old men because he wasn't a physically powerful actor (92). While not adept at stage movement, he was a powerful speaker, which leads to his late-in-life reinvention as a reader.

|

|

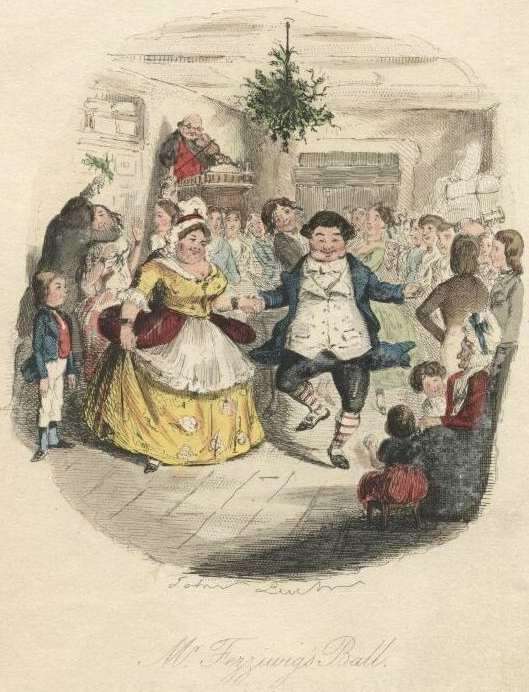

Woods finds that when Dickens read the scene at Fezziwig's ball, where Fezziwig leaps in the air, an observer notes, "Dickens clenched this moment not with a movement of his legs, as his text had it, but with 'a spasmodic shake of the head and a twist of the paper knife he held in his hand'" (92). To make up for the lack of his physical prowess and to emphasize his abilities as an orator, he would stand behind a reading desk, always holding and moving around the paper knife the observer references (92). Moreover, in a letter to his friend John Forster, Dickens admits that even when he had committed his shortened version of the Carol to memory by 1867, he still stood behind the desk and held a copy of the book, declaring himself to be a reader and no longer a performer (92).

|

Fezziwig's Ball

Wikimedia Commons

|

|

Shortly before his death, Dickens revisited America, with the intention of traveling the nation on the heels of his popular British reading tour. Before falling seriously ill, he was able to complete many readings, although not quite as many as he had hoped. His readings were immensely popular in America, inciting inspiration among many. During one of his earliest readings in Boston, Douglas-Fairhurst notes, "a Mr. Fairbanks, who attended a Christmas Eve reading of the Carol in Boston in 1867, was so moved that thereafter he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every worker a turkey" (xx). In the Hartford Currant, a journalist who was able to attend this first American reading lists other distinguished literary attendees included Longfellow, Lowe, Whittier, Holmes, and more (4). Echoing the sentiments of the audience from his first London reading, the Hartford Currant reports his "audience were now confused with laughter and anon listening with breathless interest to catch every word and every undulation of his voice" (4). Although he may have inspired a common attendee, his readings weren't completely without criticism. Following a reading the next year, a writer for the Massachusetts Teacher takes issue with Dickens' style. He finds that Dickens breaks several oratory prescripts and has a peculiar way of intoning the ends of sentences. Yet, the writer still sees Dickens as a powerful reader nonetheless, commenting, "to enjoy its full effect, one must see distinctly as well as hear. Dickens, the reader, only makes yet more manifest the genius of Dickens, the writer" (69). This sentiment seems to be shared by other journalists reporting on his American readings. Also in 1868, a reviewer from The Round Table more specifically identifies the issue with Dickens' oration style as being a fault of his Cockney accent (71).

|

Charles Dickens Readings at Steinway Hall, Boston, Mass., 1867

Wikimedia Commons

|

American Reading Tour Map

Wikimedia Commons

|

Douglas-Fairhurst asks us to be careful in being overly sentimental about these readings as they were extremely demanding and likely hastened his early death (xxix). In a letter to Charles Fechter on March 8, 1868, Dickens foreshadows his eventual fate by writing that he has had, "an American cold (the worst in the world) since Christmas Day." He further elaborates that his harsh schedule demands he energetically read four times a week in all manner of locations. He does see these readings as a necessary way to reach his audiences and he feels the importance of them through descriptions he says the Americans have given him, "I am like a 'well-to-do American gentleman,' and the Emperor of the French, with an occasional touch of the Emperor of China." His earlier trip to America, just before the writing of the Carol, left him with poor impressions of American life. His last trip to America, despite his improved social standing, was his undoing. Nonetheless, by the time of Dickens' death, he was known as Father Christmas in America just as he was in England (Douglas-Fairhurst xi).

|

"Dickens Returns on Christmas Day"

Almost a century and a half later Dickens' Carol remains a holiday classic. However, popular culture today has privileged The Carol over Dickens' other Christmas works and consequently pieces like The Chimes and The Haunted Man have fallen away from public memory. Along with the stories, our society has largely lost the fascinating and puzzling supernatural elements that were so prolific in Dickens' writing. This shift in attention does not change the fact that Dickens' played an integral part in reviving the Christmas spirit in England and in the spreading of Christmas spirits (the kind you do not imbibe) across the country and across continents. After his death, Dickens' adoring fans had a hard time letting go of "Father Christmas". In America Dickens' spirit reportedly appeared at a seance (Marks), meanwhile, his fellow Englishmen kept his spirit alive in a more metaphorical way by honoring him in a poem:

A girl in rags, staying her way-worn feet,

Cried, “Dickens dead? Will Father Christmas die?”

City he loved, take courage on the way …

Dickens returns on Christmas Day. (Foley xi)

A girl in rags, staying her way-worn feet,

Cried, “Dickens dead? Will Father Christmas die?”

City he loved, take courage on the way …

Dickens returns on Christmas Day. (Foley xi)