The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

1882

|

|

|

The Victorian era saw a

revival of the Christmas Spirit as well as a surge of curiosity regarding

spirits of a rather different nature. Oddly enough, these two

fascinations became inextricably intertwined by, in large part, the work of one

man, Charles Dickens. Dickens’ seminal ghost story, A Christmas Carol,

was not only a hit in his homeland of England, but it also gained significant

transatlantic recognition and influence in America. However, since The Carol is relatively well-known, this project will examine some of Dickens' lesser known Christmas works which he published in both book and periodical format. Throughout these pieces there lingers a curious supernatural presence which not only harkens back to an older literary tradition, but also reflects the rising trends in popular Victorian practices. Dickens' fantastically strange, yet decidedly moral Christmas tales earned him a place in both European and American hearts as "the man who reinvented Christmas,"but as time has elapsed over these much beloved stories, so have the spirits - both merry and dreary alike - faded from popular consciousness.

As a result of his famous

yuletide tale, Dickens was affectionately dubbed by his readers as “Father

Christmas,” yet his classic story and moral of generosity and good cheer was not something new to the holiday, but a

revival of a lost tradition. After the Middle Age’s strict

enforcement of the religious holiday, observance of Christmas began to wane in

England. This lack of spirit was in part due to the rapidly changing

world which had whisked away England in its progress. With the advent of

the steam engine and Darwinism, England found itself in the middle of an

industrial revolution as well as a crisis of faith. It was not until the

marriage of Queen Victoria in 1840 to German Prince Albert that Christmas began

to make a come-back. In fact, it was Prince Albert who brought England its

first Christmas tree (Grande 44). Despite this royal precedence, the

majority of the population did not celebrate the holiday with notable gusto

until after the publication of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. However, in England’s

wayward colony across the “pond” the burgeoning roots of modern Christmas had

already received a head start with the first movement for official observance

of the holiday occurring in 1836 (Foley 25). It is little wonder then, that A Christmas Carol was such a success in America as well.

Ghosts in the Hearth: the Spirits of Christmas and Victorian Fascination with the Supernatural

Dickens had not stumbled

upon something new by coupling Christmastime with scary ghost stories, in fact

this tradition was centuries in the making. The phrase “a winter’s tale,” while

most commonly associated with William Shakespeare’s play of the same title, found

its origins some time before the playwright of Stratford-upon-Avon decided to

make it immortal and was usually used in reference to a story with a

supernatural theme. As early as 1589, British playwright Christopher

Marlowe makes reference to the telling of winters’ tales in his play The Jew

of Malta (Belsey 4). However, there is reason to suspect that these

references go back as far as medieval times and the Scandinavian sagas where,

according to legend, the “haunting season” begins in December, peaks around

“yuletide,” and finally fades away around March (Belsey 5). All of these

traditions most likely date back even further to the pagan origins of Christmas

where the Winter Solstice was believed to be the day when the veil between the

living and the dead was thinnest. Dickens’ story is in part a revival of this

tradition of weaving fantastical and sometimes frightening tales around a warm

fireside on a cold winter’s night when families had little else to occupy them

but their imaginations. Unlike today, where the meaning of this phrase has all

but fallen by the wayside, it would have been common knowledge back then that a

winter’s tale was comprised of supernatural content. Perhaps this is why A

Christmas Carol was so popular, it combines both Victorian sensibility in

its moral and sensation in its ghosts.

|

While the notion of winter ghost stories was already a somewhat established tradition, Dickens is largely responsible for the association of ghost stories with Christmas day specifically. In addition to The Carol and the four other Christmas ghost stories Dickens wrote, he also filled his ensuing periodicals (Household Words and All the Year Round) with spooks, spectres, and skeptics. Dickens' ghost-mania was, to an extent, a smart move as the supernatural had become very trendy with the Victorians. This nineteenth-century curiosity in the paranormal and rise of Spiritualism took on so many faces and meanings that modern scholars have had difficulty categorizing the movement. Spiritualism was the belief that the dead communicated with the living and consequently seances became very popular during this time period (Everett). This fad incorporated many different branches of experimentation in the supernatural realm, including mesmerism - a practice that particularly fascinated Dickens.

|

Victorian Seance

Mary Evans Picture Library/Harry Price

|

In 1838 Dickens attended a demonstration of mesmerism performed by John Elliotson. The two went on to forge an odd friendship which consequently encouraged Dickens to also practice mesmerism: first on his wife, and later on Madame de la Rue in a more controversial case which helped "destabilize" Dickens' marriage (Willis & Wynne 1-3). Fellow author and friend, Wilkie Collins, would also accompany Dickens to various displays and practices of mesmerism (Pearl 164). Despite his fascination with mesmerism, Dickens was a thorough skeptic of the numerous supernatural encounters that many Victorians boasted of during the middle of the nineteenth century. However, Dickens also knew what the public wanted and thus his writings and publications reflect an interesting amalgamation of sensational ghost stories and skeptical theories.

The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

You are here •Page 3 •Page 4 •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 3 •Page 4 •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

1890

"Hear the Tolling of the Bells"

"The Chimes" by Charles Dickens, 1844

The National Gallery, London

|

Daniel Maclise, 1844

Project Gutenberg

|

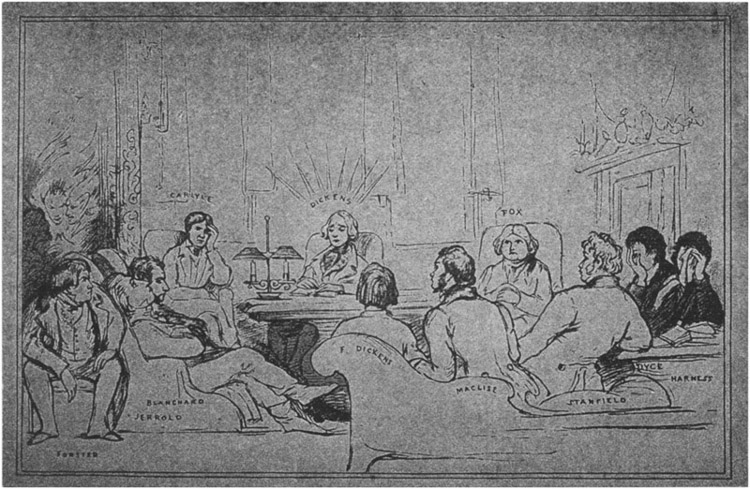

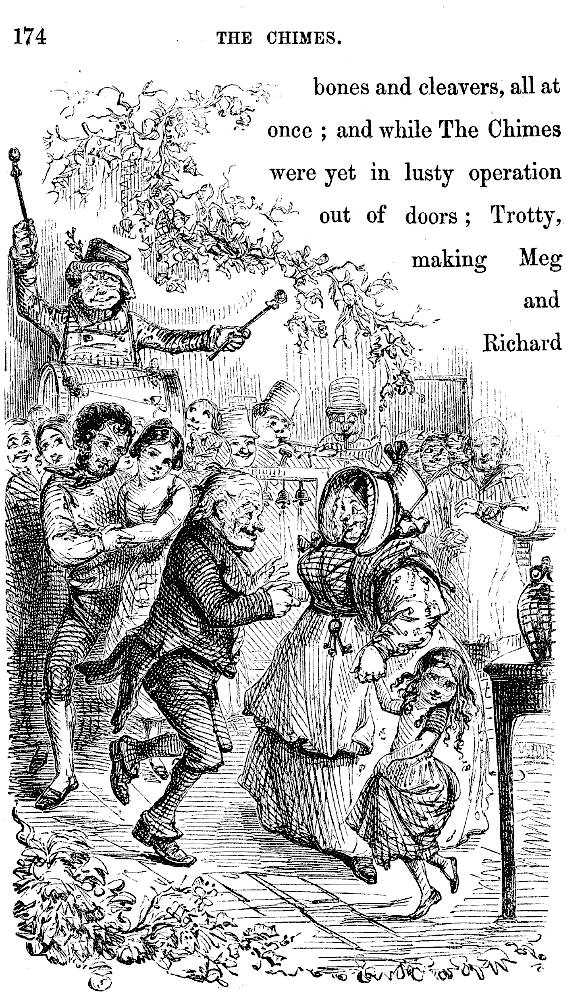

While most Dickensian scholars are very familiar with Dickens' most famous Christmas story, The Christmas Carol, very little scholarship has been done on his lesser known Christmas novellas. Despite being popular, the Carol was a financial failure for Dickens. He found financial success with the publication of four additional Christmas books in each of the following four years. The second of these was titled The Chimes, A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. In the introduction to a rare American printing of the complete version of The Chimes with pictures, H.S Nichols notes that Dickens began writing the story in Genoa@This date and location is also when and where Dickens was treating Madame de la Rue (Willis & Wynne)., where he found inspiration in the bells that rang through the city (v). He found them to be maddening, which inspired him to create the character of Trotty Veck, who loves the bells, but also goes mad from their constant sounding. Philip V. Allingham, contributing editor to the Victorian Web, notes that after Dickens finished writing the novel on November 3, 1844, he quickly returned to London to oversee the printing. On December 3, he gathered an eclectic group of friends and liberals, some of whom were inspirations for the book, for a reading. These friends included, among others, Thomas Carlyle, John Forster, and Daniel Maclise (Nichols vi-vii). Maclise memorialized the gathering in an iconic sketch reminiscent of “The Last Supper.”

|

|

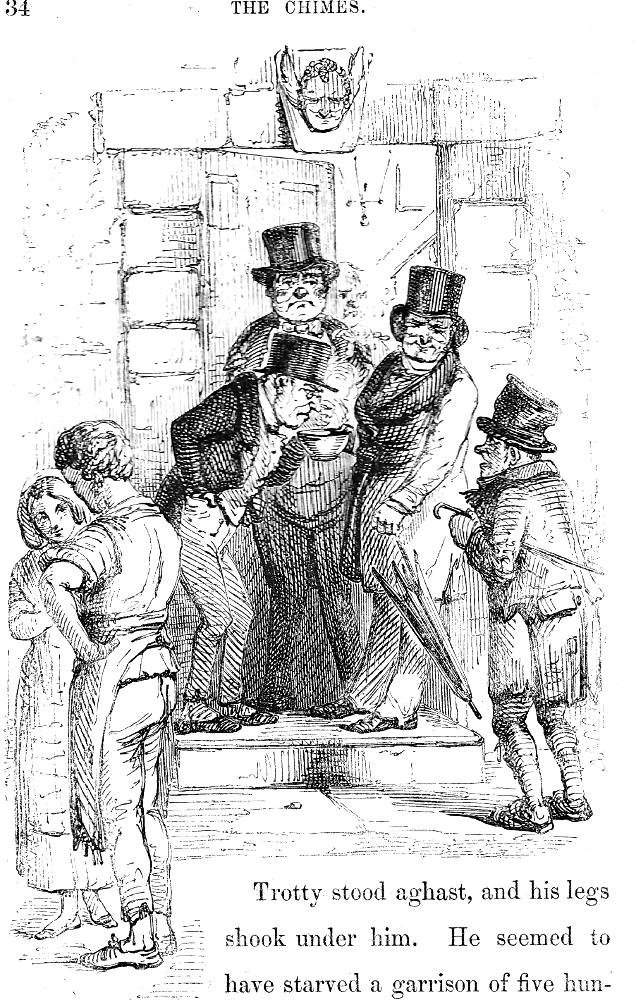

The story centers on the character of Trotty Veck (properly known as Toby or Tobias). Trotty is a poor widower and a self-employed messenger. He has an adult daughter, Meg, who is soon to be married. The story begins on New Year’s Eve and is divided into four quarters. In the first two quarters, Trotty encounters two groups of middle-class men and hears their unfortunate opinions of the working class. A hard-nosed gentleman declares, “The good old times, the grand old times, the great old times! Those were the times for a bold peasantry, and all that sort of thing” (37). When the middle-class men hear of Meg’s impending marriage, one gentleman immediately contends that the poor have no business getting married. Another of these gentlemen, Alderman Cute, goes through a list of working-class people he intends to “Put Down” including single women, boys, suicide victims, widows, and so on. Clearly, in The Chimes, the middle-class are not pleased with the poor, including Trotty and his family.

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

American Edition Edited by H.S. Nichols, 1914

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

While this book was certainly intended to be a Christmas book, a book primarily for profit, Dickens is very clearly offering a moral message. The book was very popular, a financial success, and cause for much debate after its printing. Allingham argues the reason The Chimes may have fallen out of favor as time has passed is because it is was intended to be a satire, and it is difficult for modern readers to understand it as such. Allingham points out that the 1840s were known as the “hungry forties,” and there were many events the English would have been well acquainted with (1847 potato famine, a revolutionary movement known as Chartism, riots by laborers in Manchster, rick-burning by agricultural laborers in Dorset, and rampant prostitution), and therefore would have easily read The Chimes as a social statement. Further supporting this view, Michael Slater argues the novella was heavily influenced by the ideas of Thomas Carlyle, a prominent advocate for the Chartist movement. Slater notes that both Dickens and Carlyle felt there was an impending social revolution. Moreover, they were very concerned about the “widening gap between the rich and the poor” (507). This concern is very evident in the first two quarters of The Chimes, where the working-class characters receive full character development, whereas the middle-class characters are merely used as props or stereotypes. Readers of The Chimes immediately bond with Trotty and see him as the hero of this tale.

|

|

Unfortunately for Trotty, all the middle-class chatter he overheard, regarding the poor being born bad, sinks into his subconscious. Trotty laments, “We seem to do dreadful things; we seem to give a good deal of trouble…we have no right to a New Year” (18). As he begins to internalize the persecutory messages of the middle-class, his beloved bells begin to turn on him. As they chime he hears, “Put ‘em down, Put ‘em down! Good old Times, Good old Times! Facts and figures, Facts and figures! Put ‘em down, Put ‘em down!” (49).

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

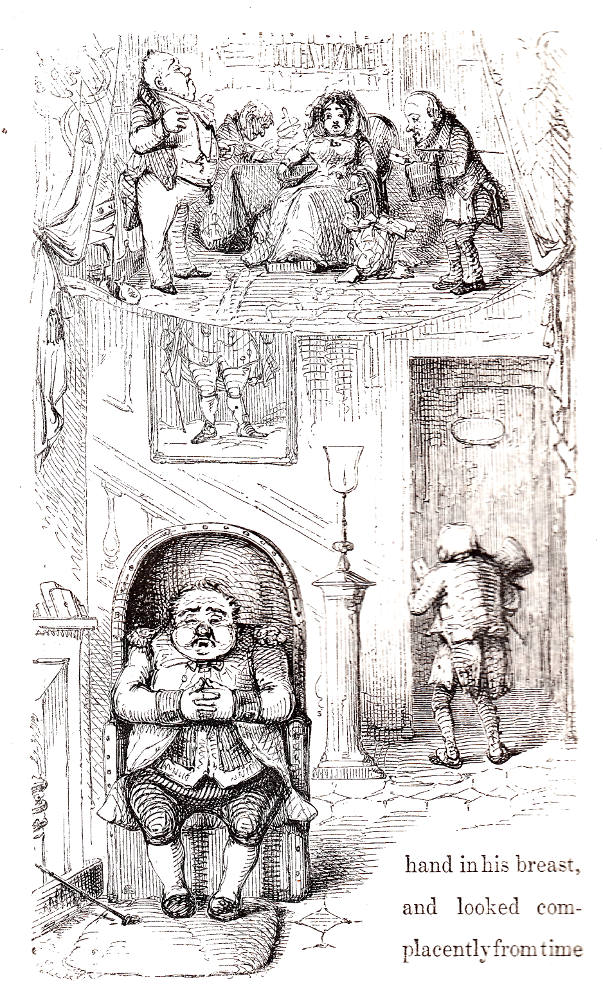

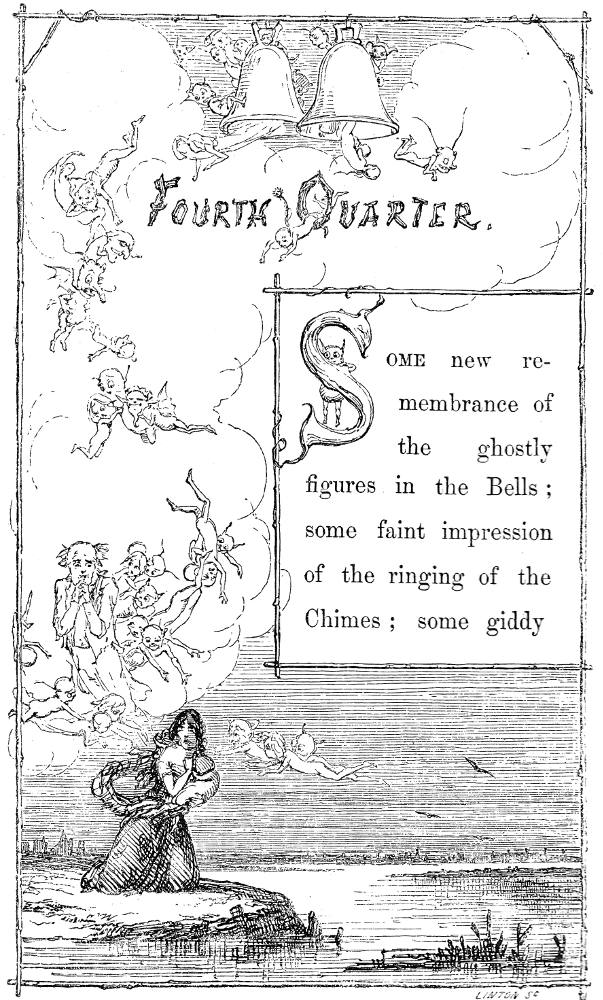

In the third quarter, Trotty is drawn in by the bells, who intend to teach him a lesson about his newly formed opinions. When he enters the tower he sees it is “swarming with dwarf phantoms, spirits, elfin creatures of the Bells” (96). These creatures transform him into a dreamlike state, where he believes he died nine years previous, and is accompanied by a child spirit to see how his daughter is faring (reminiscent of the Carol’s Ghost of Christmas Past). Unfortunately, we find in the fourth quarter, because she never married and instead lived a life according to the beliefs of the middle-class men, her life has not turned out well. The bells demand that Trotty learn a lesson from the one person closest to him in life. He of course promises that he has learned his lesson, and he eventually wakes only to realize that it has all been a dream and is forever a changed man.

|

|

There are a myriad of fantastical creatures in this story, taking the spirits in the Carol a step further. In the tower, there are, as can be seen in the illustrations, cherubs, ghouls, demons, ghosts, and more. Moreover, in the dream sequence, Trotty is a ghost, along with his spirit-child companion. As has been established, ghost stories were a popular genre during the Victorian Christmas. Dickens, however, prefers to make the ghosts in his ghost stories moral lessons. As will be seen in a Gaskell ghost story found in Household Words, this formula does not hold true for all writers of Christmas or Gothic ghost stories. The Dickensian formula revolves around a central character that needs to learn a lesson, which he learns with the help of spirits; spirits that appear in a dream-like state, and spirits that only he can see. This formula could be symptomatic of his general skepticism surrounding ghosts. In his introduction to a collection of all five Christmas books, Douglas-Fairhurst writes, "Dickens, who, like many of his contemporaries, routinely mocked the belief in ghosts as a lingering trace of the uncivilized past, but also found it impossible to shake more primitive feelings of dread out of his mind or voice" (xiii). Dickens was able to appeal to the genre of ghost stories through his dream-state formula, while remaining distant to the idea of ghosts as a conscious reality.

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

Despite having fallen out of popularity, modern readers may actually find familiarity in the story. There are several theories as to where Dickens found inspiration for The Chimes as well as who Dickens inspired with this novella. The bells in Genoa may not have been Dickens' only inspiration. Marilyn Kurata argues that Dickens also found transatlantic inspiration in the figure of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Kurata notes that, upon his return from America in 1842, he gave his close friend John Forster a copy of Moses from an Old Manse (10). In this collection, Hawthorne included “Young Goodman Brown,” written in 1835, nine years prior to the writing and publication of The Chimes. Kurata finds similarities in the hero of the stories: night journeys, fantastical visions, and innocents that lose their faith (11). Although the heroes do seem to follow a pattern, the purpose and effects of each are drastically different, with “Brown” being vastly darker and arguably scarier, and The Chimes more of an uplifting moral message. While the similarities are hard to dispute, Kurata’s observations seem to locate a vague similarity in the story lines.

|

|

If Dickens was influenced by an American author, he certainly paid the favor back by being a significant influence for Edgar Allan Poe. If a reader is at all familiar with Poe’s “The Bells,” the possible connection between the two works is evident within the first few pages of The Chimes. The melodious tone and specific phrases can be linked directly to Poe’s poem. One such familiar line occurs when the narrator of The Chimes declares the bells are “high up in the steeple!” (4). These connections continue throughout the novel in various instances including: “Up, up, up; and climb and clamber; up, up, up; higher, higher, higher up!” (92), “…heard them howl” (97), “he saw them representing, here a marriage ceremony, there a funeral; in this chamber an election, and in that a ball; everywhere, restless and untiring motion” (97), “..uproar of the bells” (97), and “Goblin of the Bell” (100). Another obvious similarity is the structure, both being in four quarters. These claims are further strengthened in an article by Burton Pollin. Pollin notes that Poe had a deep reverence for Dickens, despite Dickens' refusal to give Poe publishing favors. Moreover, Pollin provides proof that Poe certainly had an opportunity to read The Chimes before writing “The Bells.” The Chimes was printed, without Dickens' consent, in the New-York Evening Mirror on Jan 28, 1845, printed in the space just before Poe’s “The Raven.” Pollin also points to a now lost book, published by a close friend of Poe, Frederick W. Thomas, upon Poe’s death. Before it was lost, some transcriptions quote Thomas as saying that The Chimes was Poe’s final inspiration for “The Bells.”

|

“The Chimes” by Charles Dickens, 1844

Victorian Web

|

While many modern readers, even Dickens enthusiasts, may have previously overlooked The Chimes in Dickens' great body of works, it still stands as an important contributor to Dickens’ place in history as Father Christmas.

The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

•Page 3

You are here •Page 4 •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 4 •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

1889

|

...

|

|

...

|

|

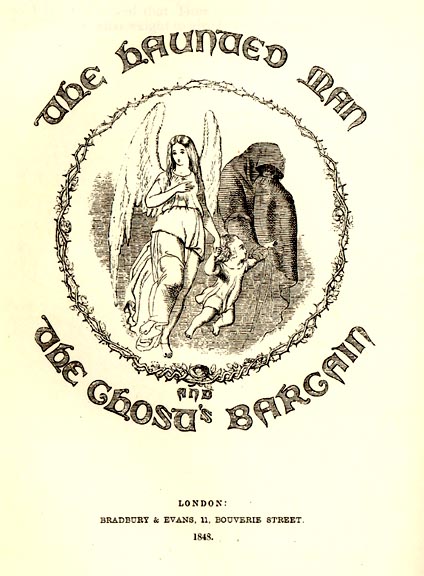

The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain is Dickens’ final independently published Christmas ghost story. Although it was relatively popular at its release in 1848, ironically, The Haunted Man seems to have quickly dwindled from public memory. It begins similar to Dickens’ other Christmas books – a lonely old man, Mr. Redlaw, sits by himself in front of his fire – yet the “ghost” of this story is not the spectre of someone long since deceased, but rather Redlaw’s own self in the form of a phantom doppelgänger. In addition to being undead, the spirit is also a familiar one to the protagonist. Redlaw is neither surprised nor terrified when he senses his phantom-self lurking behind his arm chair. The “ghost” of this tale offers to make a deal with the wallowing Mr. Redlaw – he will take away every memory of wrong and sorrow from him with the caveat that: |

The gift I have given you, you shall give again, go where you will. Without recovering yourself the power that you have yielded up, you shall henceforth destroy its like in all whom you approach. Your wisdom has discovered that the memory of sorrow, wrong, and trouble is the lot of all mankind, and that mankind would be happier, in its other memories, without it. Go! Be its benefactor! Freed from such remembrance, from this hour, carry involuntarily the blessing of such freedom with you. (Dickens 45)

Mrs. Williams decorating Redlaw's chambers

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain

|

For being a Christmas story, there is very little reference to the holiday in The Haunted Man. The reader knows it its winter from how the narrator introduces Mr. Redlaw, "there, upon a winter night, alone," but it is not until his servants arrive on the scene and the pure-hearted Mrs. Williams begins decorating his chambers with festive branches that we learn Christmas is nigh (Dickens 3). The ensuing conversation between Redlaw and the elderly Mr. Philip Williams reveals the theme of the story as they discuss the memories of Christmases past and how Redlaw would sooner forget all of his painful memories while Philip's most cherished possession- and secret to staying sharp at his age- are his memories, both good and bad. Aside from this interaction though there is very little holiday cheer in this story.

|

Mr. Redlaw in his chair with the "Ghost" behind

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain

|

|

Similar to both A Christmas Carol and The Chimes, the characters in The Haunted Man span from lower class to middle/upper-middle

class. Mr. Redlaw is at the top of the social ladder while the other

characters, such as the Williams, the Tetterbys and the poor orphan boy occupy

the lower rungs. Interestingly though, despite the obvious

social hierarchy of the characters, the story is not so much about

charity - as is the case with The Carol - but rather about the importance of remembering

past sorrows and wrongs and learning to forgive and show compassion towards

others who might be suffering.

According to the phantom's warning, Redlaw will pass on his "gift" to all whom he encounters; however, there are a couple exceptions to this rule. The amiable Mrs. Milly Williams and the orphan boy are unharmed by Redlaw's presence while others whom he encounters forget their past wrongs and in turn become bitter people. The orphan boy has not lived enough life to differentiate between wrong and right and thus has nothing to forget and Milly is the very picture of purity. In fact Milly acts as everyone's guardian angel and has learned the secret to forgiving and cultivating bad memories into reminders of the universality of pain, thus, Redlaw's gift cannot pass onto her either. |

Illustration of First Chapter

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain

|

At the story's conclusion we are reintroduced to the holiday season and reminded that Christmas is "a time in which...the memory of every remediable sorrow, wrong, and trouble in the world around us, should be active with us," and thus it is natural that these painful, yet necessary memories should be all the more strong and sacred during the holiday season as a reminder of forgiveness. On this note of moral platitude, Dickens ends his Christmas novella career and sets off on a rather different endeavor in publishing. Despite this change though, Dickens does not forsake his yuletide role, but rather transforms it into a format that best fits his new path - Christmas periodicals.

The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

•Page 3

•Page 4

You are here •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 5 •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

1888

The Xmas No. of Household Words

|

Every Christmas in its nine year run, Dickens’ Household Words published a special Christmas issue. Special Christmas publications were certainly not a new phenomenon, but as with many things Christmas, Dickens was certainly the most successful practitioner of the “Christmas Number.” According to the Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism, the idea of Christmas publications seems to begin in the 1820s with special gift books, or “Books of Beauty,” created by Annuals. These gift books inspired Dickens and other authors to publish Christmas books in the “Hungry Forties” (the Carol, Chimes, and Haunted Man among these). Also in the 1840s, Punch was the first periodical to begin publishing Christmas issues.

|

Detail of: Heath's Book of Beauty, 1833

Wikimedia Commons

|

Household Words, December 1850

Charles Dickens

|

In its first year of publication, Dickens arranged for multiple contributors to write articles examining how Christmas was celebrated all over the world and by different classes of people. This first collection was published on December 21,1850, as part of the regular weekly publication, but with a special title “The Christmas Number.” He began this collection with an autobiographical description of his own Christmas remembrances which he called “A Christmas Tree.” In “A Christmas Tree,” as well as in the organization of the entire first issue, we can find hints as to how Dickens conceives of Christmas and how he envisions his Christmas publications.

|

His autobiographical sketch describes a Christmas tree through his own boyhood remembrances. He gives many detailed descriptions of its ornamentations, smell, and nostalgic meaning. He exclaims, “oh, now all common things become uncommon and enchanted to me. All lamps are wonderful; all rings are talismans” (291). Dickens sees Christmas as a magical and nostalgic holiday; a holiday celebrated by all. For the other articles published in the issue, Dickens recruited contributors to describe experiences of Christmas in British colonies like India and Australia: exotic locations where magical things happen.

For Dickens, Christmas is not only a magical holiday, but also a community holiday where family and friends gather and share. He declares, “and I do come home at Christmas. We all do, or we all should” (292). The return to family and one’s roots seems to be a theme that echoes throughout Dickens' Christmas tales and echoed in future Christmas numbers. Describing this time with family he recalls, “there is probably a smell of roasted chestnuts and other good comfortable things all the time, for we are telling Winter stories – Ghost stories, or more shame for us – round the Christmas fire” (293). This theme of telling stories around the fire, especially ghost stories, resonates throughout the Christmas numbers.

After this first experiment in dedicating a weekly issue to Christmas, Dickens endeavored to separate the issue from the weekly. Each of the following years, Household Words published a special “Christmas Number.” The first of these appeared in 1851, for 2 pence, and was around 35 pages long. Owing to its success, in 1852, the price was raised to 3 pence where it remained until the termination of Household Words. According to the Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism, a regular weekly circulation of Household Words ranged around 40,000 copies. However, the Christmas Issues sold 100,000 copies or more and provided the additional advantage of increasing circulation of the weekly publication every spring.

|

In the 1851 issue, not much changed as far as the style of the publication. Dickens solicited articles from various contributors for a nostalgic collection of Christmas remembrances. The first of these, Dickens authored himself, “What Christmas is, as we Grow Older.” In early December, Dickens wrote to his sub-editor Wills, “I can’t begin the Xmas article and am going out to walk, after vain trials” (75). Although what followed was only a short article, it encapsulates Christmas for Dickens as he evolved into his role as Father Christmas. He implores, “as we grow older, let us be more thankful that the circle of our Christmas associations and of the lessons that they bring, expands!” (1). This article, along with the collection that follows, resonates with Dickens' ambition to make the Christmas issue something that all readers can relate to. In the same letter, Dickens explains to Wills, “It seems to me that what the Xmas No. wants is something with no detail in it, but a tender fancy that shall hit a great many people” (75).

|

Household Words, December 1851

Charles Dickens

|

Household Words, December 1852

Charles Dickens

|

Dickens continues the patter of gathering contributions from various authors in the following year’s issue; however, this issue makes a major shift away from the nostalgia and "tender fancy" Dickens previously wanted. In 1852, the Christmas issue was a collection of tales called, “A Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire.” In this third number, Dickens hearkens to the nostalgia seen in the previous issues with the title, but begins on a new path with the collection: fictional short stories. He was very careful with this new issue and the new endeavor, as is obvious in his letters to Wills in November 1852, about the types of articles he would prefer to publish. He declines to publish a story by Georginia Craik as, “her imitation of me is too glaring – I never saw anything so curious” (93). Although he would not publish Craik in the Christmas number (publishing her in February of the following year) he was enamored with Harriet Martineau’s “The Deaf Playmate’s Story. He calls it, “very affecting – admirably done…I couldn’t wish for better” (93). It is a rather sad story, with a happy ending. The narrator, a young boy, begins to have trouble with his ears and eventually becomes very hard of hearing. He has a close friend that sticks by his side, through quarrels and his disability, the playmate was a source of strength for the narrator. This story, along with others in the collection, was not about Christmas, but in the sentimental tradition of story-telling around the fire.

|

Such a tradition would not be complete without a ghost story, provided in the 1852 issue by Elizabeth Gaskell. Before reading Gaskell’s story, in a letter to Wills, Dickens observes, “it is long” (93). It certainly is the longest addition to the Christmas issue, but an addition that Dickens felt worthy of entry, with some hesitation. The “Old Nurse’s Story” revolves around a nurse being left in charge of a baby after its mother dies. The nurse and the baby relocate to a wealthy relative of the baby, in a brooding, dark, and mysterious mansion. The mansion contains many objects, which raise the sensationalist spectacle of the story, “we could manage to see old China jars and carved ivory boxes, and great heavy books, and, above all, the old pictures!” (13). The objects described seem to be oriental and magical. Old pictures often dredge up memories of the dead, literally as proves to be the case in this story. Making reference to the time of year where the dead are thought to rise, the nurse notes, “as winter drew on, and the days grew shorter, I was sometimes almost certain that I heard a noise as if some one was playing on the great organ in the hall” (14). Although her companions balked at her reports of mysterious music, her premonitions of hauntings prove a reality, for everyone in the home. The hauntings seem to be, as with Dickens' hauntings, a philosophical reminder of the bad deeds of the past. Gaskell’s story remains one of the best examples of a Gothic ghost story. However, upon his initial reading, Dickens felt the ending could have been edited to better effect. In a letter to Gaskell on December 1, 1852, he writes “I send to you the proof of ‘The Old Nurse’s Story,’ with my proposed alteration. I shall be glad to know whether you approve of it" (340). Gaskell heartily rejected his proposal for the ending, which eliminated the ability of everyone to see the specters, limiting their view to only the nurse and the child. This ending would seem more reminiscent of Dickens' own ghosts, being only viewable to the character who needs to see them. As he confirms in his letter to Gaskell’s rejection, “I don’t claim for my ending of ‘The Nurse’s Story’ that it would have made it a bit better. All I can urge in its behalf is, that it is what I should have done myself. But there is no doubt of the story being admirable as it stands…(342))”. It was published in the Christmas number as it stood, allowing Gaskell’s contribution to the Gothic horror to be truly her own.

|

As the Christmas issues progressed, they continued to revolve around the idea of fireside storytelling, gradually becoming less about Christmas, but all with a central purpose for the telling of stories. In the 1854 edition, titled “The Seven Poor Travelers,” the narrator stays at an inn on Christmas Eve, only to discover there are lodgings behind the inn provided at charity to six poor travelers. He invites them for dinner and they exchange stories, with the narrator being the seventh traveler. In the 1856 edition, which he worked closely with Wilkie Collins to produce, the stories emanate from the sinking of the Golden Mary, after which the crew and passengers must pass five days’ time waiting to be rescued on life boats. The collection of stories results from their time at sea, with no apparent connection to Christmas. On April 1 of the following year, Dickens writes to Wills, "I think, in such a case as that of Collins's, the right thing is to give 50 pounds. I think it right, abstractedly, in the case of a careful and good writer on whom we can depend for Xmas Nos. and the like" (218). His generous payment (for which he was notorious and for which he was constantly at odds with Wills) proves to be a good pay off, for Collins continued to contribute to the Christmas numbers every year thereafter.

|

Household Words, December 1854

Charles Dickens

|

Household Words, December 1858

Charles Dickens

|

The last Christmas number appeared in 1858 and was titled “A House to Let.” Although both Gaskell and Adelaide Anne Procter were contributors to this number, Dickens and Collins collaborated extensively on the issue. On November 20, 1858, Dickens writes to Wills, “…Wilkie and I have arranged to pass the whole day here…to connect the various portions of the Xmas No. and get it finally together” (256). After leaving Household Words, thus dismantling the magazine altogether, Dickens did not abandon his role of Father Christmas, continuing with Christmas publications in All the Year Round and later solidifying his place in history though his public readings.

|

The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

•Page 3

•Page 4

•Page 5

You are here •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 6 •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

1887

All The Year Round

ATYR Regular Dec. issue

Dec. 24th 1859

|

After Dickens split with his sub-editor,

Wills, he began his next endeavor in periodical publishing with his final

journal All the Year Round (ATYR) in 1859. Like its predecessor, Household Words, ATYR

also published extra, collaborative, Christmas Numbers. While Household

Words was aimed at middle-class readership, ATYR sought its audience in the upper stratosphere of the middle

class. Yet despite its slightly more sophisticated readers (or perhaps because

of them), ghost stories abound in ATYR.

Although spooks revealed themselves year round within the periodical, they

gained a special momentum during the yule season, particularly in the Christmas

numbers.

The Christmas numbers did not replace the normal publications, but rather supplemented them with a doubly long collaborative piece that usually followed a united story line throughout the number. Depending on the publishing schedule, regular issues of ATYR were released on both Christmas Eve and day. Many of the periodical’s December issues included some manner of supernatural story. Interestingly enough, these “winter tales” take on multiple forms: sensational spectres, “real life” ghost encounters, philosophical quandaries on the paranormal, and outright skepticism. This variety of tales reflects both Victorian curiosity with the supernatural and Dickens’ own suspicious fascination with the unknown. |

|

Ad for Extra Christmas Number

Dec. 1860

|

|

In the very first Christmas edition of ATYR, Dickens joined forces with his

partner in spiritual investigation – Wilkie Collins – to create a thrilling

tale of a haunted house. This publication is strikingly different from his first Christmas issue of Household Words which focused more on Christmas cheer and less on winter ghosts. Along with

Dickens and Collins, other notable writers joined the collaborative team, such

as Elizabeth Gaskell, and on December 13th 1859 “The Haunted House”

was published for public consumption. It

is interesting that the very first Christmas number of ATYR should be solely comprised of stories of paranormal investigation

and according to Louise Henson, this particular issue may have been inspired by

a tiff with former Household Words

contributor William Howitt. Apparently Howitt

had complained to Dickens about one of his more skeptical articles in ATYR which “cast doubt on the

authenticity of spiritual communications between the living and the dead”

(Henson 55). Dickens replied to him stating that he was “perfectly unprejudiced

and impressionable on the subject” and in turn offered to investigate any “suitably

haunted” house that Howitt suggested (Henson 55). This incident thus became the inspiration for

“The Haunted House” Christmas edition and the beginning of an ongoing spiritual

debate with Howitt.

|

First Christmas Number of ATYR

Dec. 13th 1859

|

Dickens' Final Collaborative Work

Dec. 12th 1867

|

ATYR's extra Christmas numbers sold better than the regular December editions and as Dicken's wrote in a letter to Collins regarding the 1864 number: "The Christmas number has been

the greatest success of all; has shot ahead of last year; has sold about two

hundred and twenty thousand; and has made the name of Mrs. Lirriper so swiftly

and domestically famous as never was" (Dickens). For the next six years Dickens continued to collaborate with other popular authors of the time to create these extra Christmas numbers until his death in 1870.

|

Christmas Number Containing "The Signal Man"

Dec. 12th 1866

|

The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

•Page 3

•Page 4

•Page 5

•Page 6

You are here •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 7 ♦Endnotes »Next page

1886

Becoming Father Christmas

Ten years after his festive ghost story first went to press, Dickens began a tradition which his great-great grandson, Gerald Dickens, continues to this day. This tradition has caused A Christmas Carol to leave an indelible impression on the world: public readings. Dickens had a life-long love of performing. In her article examining Dickens' early performing life, Leigh Woods notes that Dickens held twenty-three roles as an actor between the ages of twenty-one and forty-five, performing in theatrical productions until 1857 (90). Just a few years before the end of his acting career, in 1853 Dickens gave his first public reading of A Christmas Carol. According to Douglas-Fairhurst, this reading opened up a new outlet for Dickens to share with his audience. Consequently, he gave 127 readings of the Carol from this date until his death in 1870 (xxviii).

Charles Dickens Reading

Charles A. Barry, via Wikimedia Commons

|

Gerald Dickens

Wikimedia Commons

|

1858 Reading Tour

Wikimedia Commons

|

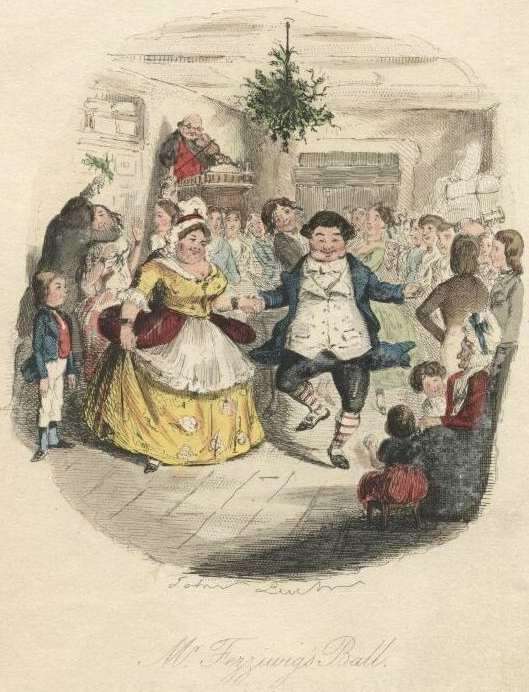

In 1857, the final year of his acting career, Dickens first read the Carol to a London audience. According to a London Times article (later reprinted in the American Littell's Living Age), this first London reading was met with great success. The article writer notes that his audience was, "in a state of breathless interest" during the two hour reading (544). Also in this review, the writer observes that Dickens does not try to impersonate any character, with the exception of Scrooge, whom he impersonates with "senile accents" (544). Woods claims that much can be learned about Dickens'readings based on his choices and casting as an actor. She argues that Dickens often played old men because he wasn't a physically powerful actor (92). While not adept at stage movement, he was a powerful speaker, which leads to his late-in-life reinvention as a reader.

|

|

Woods finds that when Dickens read the scene at Fezziwig's ball, where Fezziwig leaps in the air, an observer notes, "Dickens clenched this moment not with a movement of his legs, as his text had it, but with 'a spasmodic shake of the head and a twist of the paper knife he held in his hand'" (92). To make up for the lack of his physical prowess and to emphasize his abilities as an orator, he would stand behind a reading desk, always holding and moving around the paper knife the observer references (92). Moreover, in a letter to his friend John Forster, Dickens admits that even when he had committed his shortened version of the Carol to memory by 1867, he still stood behind the desk and held a copy of the book, declaring himself to be a reader and no longer a performer (92).

|

Fezziwig's Ball

Wikimedia Commons

|

|

Shortly before his death, Dickens revisited America, with the intention of traveling the nation on the heels of his popular British reading tour. Before falling seriously ill, he was able to complete many readings, although not quite as many as he had hoped. His readings were immensely popular in America, inciting inspiration among many. During one of his earliest readings in Boston, Douglas-Fairhurst notes, "a Mr. Fairbanks, who attended a Christmas Eve reading of the Carol in Boston in 1867, was so moved that thereafter he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every worker a turkey" (xx). In the Hartford Currant, a journalist who was able to attend this first American reading lists other distinguished literary attendees included Longfellow, Lowe, Whittier, Holmes, and more (4). Echoing the sentiments of the audience from his first London reading, the Hartford Currant reports his "audience were now confused with laughter and anon listening with breathless interest to catch every word and every undulation of his voice" (4). Although he may have inspired a common attendee, his readings weren't completely without criticism. Following a reading the next year, a writer for the Massachusetts Teacher takes issue with Dickens' style. He finds that Dickens breaks several oratory prescripts and has a peculiar way of intoning the ends of sentences. Yet, the writer still sees Dickens as a powerful reader nonetheless, commenting, "to enjoy its full effect, one must see distinctly as well as hear. Dickens, the reader, only makes yet more manifest the genius of Dickens, the writer" (69). This sentiment seems to be shared by other journalists reporting on his American readings. Also in 1868, a reviewer from The Round Table more specifically identifies the issue with Dickens' oration style as being a fault of his Cockney accent (71).

|

Charles Dickens Readings at Steinway Hall, Boston, Mass., 1867

Wikimedia Commons

|

American Reading Tour Map

Wikimedia Commons

|

Douglas-Fairhurst asks us to be careful in being overly sentimental about these readings as they were extremely demanding and likely hastened his early death (xxix). In a letter to Charles Fechter on March 8, 1868, Dickens foreshadows his eventual fate by writing that he has had, "an American cold (the worst in the world) since Christmas Day." He further elaborates that his harsh schedule demands he energetically read four times a week in all manner of locations. He does see these readings as a necessary way to reach his audiences and he feels the importance of them through descriptions he says the Americans have given him, "I am like a 'well-to-do American gentleman,' and the Emperor of the French, with an occasional touch of the Emperor of China." His earlier trip to America, just before the writing of the Carol, left him with poor impressions of American life. His last trip to America, despite his improved social standing, was his undoing. Nonetheless, by the time of Dickens' death, he was known as Father Christmas in America just as he was in England (Douglas-Fairhurst xi).

|

"Dickens Returns on Christmas Day"

Almost a century and a half later Dickens' Carol remains a holiday classic. However, popular culture today has privileged The Carol over Dickens' other Christmas works and consequently pieces like The Chimes and The Haunted Man have fallen away from public memory. Along with the stories, our society has largely lost the fascinating and puzzling supernatural elements that were so prolific in Dickens' writing. This shift in attention does not change the fact that Dickens' played an integral part in reviving the Christmas spirit in England and in the spreading of Christmas spirits (the kind you do not imbibe) across the country and across continents. After his death, Dickens' adoring fans had a hard time letting go of "Father Christmas". In America Dickens' spirit reportedly appeared at a seance (Marks), meanwhile, his fellow Englishmen kept his spirit alive in a more metaphorical way by honoring him in a poem:

A girl in rags, staying her way-worn feet,

Cried, “Dickens dead? Will Father Christmas die?”

City he loved, take courage on the way …

Dickens returns on Christmas Day. (Foley xi)

A girl in rags, staying her way-worn feet,

Cried, “Dickens dead? Will Father Christmas die?”

City he loved, take courage on the way …

Dickens returns on Christmas Day. (Foley xi)

The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

•Page 3

•Page 4

•Page 5

•Page 6

•Page 7

You are here ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here ♦Endnotes »Next page

1938

Works Cited

Allingham, Philip V. "The Chimes Illustrated: Ten Woodcuts and Two Steel

Engravings." The Victorian Web. N.p., 16 Jan. 2007. Web. 1 May 2013.

Belsey, Catherine. "Shakespeare’s Sad Tale for Winter: Hamlet and the Tradition of Fireside Ghost Stories." Shakespeare Quarterly 1st ser. 61 (2010): 1-27. Project Muse. Web.

Dickens, Charles, and Robert Douglas-Fairhurst. A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Books. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006.

Dickens, Charles. Charles Dickens As Editor Being Letters Written to Him by William Henry Wills His Sub-editor. Ed. R.C. Lehmann. London:

Smith, Elder &, 1912.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Issue." Household Words 21 Dec. 1850: 289-312. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1851: 1-24. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1852: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1854: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1856: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1858: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. Ed. H.S. Nichols. New York: n.p.,

1914.

Dickens, Charles. "The Haunted House." All the Year Round 13 Dec. 1859. Open Library. Web.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1848. Googlebooks. Google. Web.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens Volume 1. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1879.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens Volume 2. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1879.

Dickens, Charles. "Mugby Junction." All the Year Round 12 Dec. 1866. Open Library. Web.

Dickens, Charles. "No Thoroughfare." All The Year Round 12 Dec. 1867. Wikimedia Commons. Web.

Drew, John. "Christmas Issues." Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism. N.p.: n.p., n.d. C19. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

Foley, Daniel J. Christmas in the Good Old Days, a Victorian Album of Stories, Poems, and Pictures of the Personalities Who Rediscovered Christmas. Philadelphia: Chilton, Book Division, 1961. Print.

Grande, Laura. "How Dickens Saved Christmas." History Magazine Dec. 2011: n. pag. JSTOR. Web. 31 Jan. 2013.

Henson, Louise. "Investigations and Fictions: Charles Dickens and Ghosts." The Victorian Supernatural. Ed. Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2004. 44-63. Print.

Kurata, Marilyn. "Dicken's Re-Casting of "Young Goodman Brown"" American Notes and Queries 22 (1983): 10-12.

Marks, Thomas. "A Hankering After Ghosts: Charles Dickens and the Supernatural, British Library, Review." The Telegraph. 30 Nov. 2011. Web.

"Mr. Charles Dickens' "Reading"" Littell's Living Age 29 Aug. 1857: 544. American Periodicals Series Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

"Mr. Dickens’s Elocution." The Round Table. A Saturday Review of Politics, Finance, Literature, Society, and Art 1 Feb. 1868: 71. American

Periodicals Series Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

"Mr. Dickens’s Inaugural Reading." Hartford Daily Courant 4 Dec. 1867: 4. American Periodicals Series Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

Noakes, Richard. "Spiritualism, Science and the Supernatural in Mid-Victorian Britain." The Victorian Supernatural. Ed. Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2004. 23-43. Print.

Pearl, Sharrona. "Dazed and Abused: Gender and Mesmerism in Wilkie Collins." Victorian Literary Mesmerism. By Martin Willis and Catherine Wynne. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 163-82. Print.

Pollin, Burton. "Dickens's Chimes and Its Pathway into Poe's "Bells"" Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Culture 51.2 (1998): n. pag.

MLA International Bibliography. Web. 1 May 2013.

"Readings by Charles Dickens." , Massachusetts Teacher and Journal of Home and School Education Feb. 1868: 69. American Periodicals Series

Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

Slater, Michael. "Carlyle and Jerrold Into Dickens: A Study of The Chimes." Nineteenth-Century Fiction 24.4 (1970): 506-26.

Willis, Martin, and Catherine Wynne. "Introduction." Victorian Literary Mesmerism. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. Print.

Woods, Leigh. "“As If I Had Been Another Man”: Dickens, Transformation, and an Alternative Theater." Theater Journal 40.1 (1988): 88-100.

Belsey, Catherine. "Shakespeare’s Sad Tale for Winter: Hamlet and the Tradition of Fireside Ghost Stories." Shakespeare Quarterly 1st ser. 61 (2010): 1-27. Project Muse. Web.

Dickens, Charles, and Robert Douglas-Fairhurst. A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Books. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006.

Dickens, Charles. Charles Dickens As Editor Being Letters Written to Him by William Henry Wills His Sub-editor. Ed. R.C. Lehmann. London:

Smith, Elder &, 1912.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Issue." Household Words 21 Dec. 1850: 289-312. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1851: 1-24. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1852: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1854: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1856: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. "Christmas Number." Household Words Dec. 1858: 1-36. Open Library. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. Ed. H.S. Nichols. New York: n.p.,

1914.

Dickens, Charles. "The Haunted House." All the Year Round 13 Dec. 1859. Open Library. Web.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1848. Googlebooks. Google. Web.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens Volume 1. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1879.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens Volume 2. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1879.

Dickens, Charles. "Mugby Junction." All the Year Round 12 Dec. 1866. Open Library. Web.

Dickens, Charles. "No Thoroughfare." All The Year Round 12 Dec. 1867. Wikimedia Commons. Web.

Drew, John. "Christmas Issues." Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism. N.p.: n.p., n.d. C19. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

Foley, Daniel J. Christmas in the Good Old Days, a Victorian Album of Stories, Poems, and Pictures of the Personalities Who Rediscovered Christmas. Philadelphia: Chilton, Book Division, 1961. Print.

Grande, Laura. "How Dickens Saved Christmas." History Magazine Dec. 2011: n. pag. JSTOR. Web. 31 Jan. 2013.

Henson, Louise. "Investigations and Fictions: Charles Dickens and Ghosts." The Victorian Supernatural. Ed. Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2004. 44-63. Print.

Kurata, Marilyn. "Dicken's Re-Casting of "Young Goodman Brown"" American Notes and Queries 22 (1983): 10-12.

Marks, Thomas. "A Hankering After Ghosts: Charles Dickens and the Supernatural, British Library, Review." The Telegraph. 30 Nov. 2011. Web.

"Mr. Charles Dickens' "Reading"" Littell's Living Age 29 Aug. 1857: 544. American Periodicals Series Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

"Mr. Dickens’s Elocution." The Round Table. A Saturday Review of Politics, Finance, Literature, Society, and Art 1 Feb. 1868: 71. American

Periodicals Series Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

"Mr. Dickens’s Inaugural Reading." Hartford Daily Courant 4 Dec. 1867: 4. American Periodicals Series Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

Noakes, Richard. "Spiritualism, Science and the Supernatural in Mid-Victorian Britain." The Victorian Supernatural. Ed. Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2004. 23-43. Print.

Pearl, Sharrona. "Dazed and Abused: Gender and Mesmerism in Wilkie Collins." Victorian Literary Mesmerism. By Martin Willis and Catherine Wynne. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 163-82. Print.

Pollin, Burton. "Dickens's Chimes and Its Pathway into Poe's "Bells"" Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Culture 51.2 (1998): n. pag.

MLA International Bibliography. Web. 1 May 2013.

"Readings by Charles Dickens." , Massachusetts Teacher and Journal of Home and School Education Feb. 1868: 69. American Periodicals Series

Online. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

Slater, Michael. "Carlyle and Jerrold Into Dickens: A Study of The Chimes." Nineteenth-Century Fiction 24.4 (1970): 506-26.

Willis, Martin, and Catherine Wynne. "Introduction." Victorian Literary Mesmerism. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. Print.

Woods, Leigh. "“As If I Had Been Another Man”: Dickens, Transformation, and an Alternative Theater." Theater Journal 40.1 (1988): 88-100.

The Man Who Reinvented Christmas: Dickens and the Spirits of Christmas

desireelong

Endnotes

1 This date and location is also when and where Dickens was treating Madame de la Rue (Willis & Wynne).

Links

Page 2

"The Bells" http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/medny/venturi-poebells.html